Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital and University o f Pennsylvania

Special methodological problems are raised when human subjects are used in psychological experiments, mainly because subjects' thoughts about an experiment may affect their behavior in carrying out the experimental task.

To counteract this problem psychologists have frequently felt it necessary to develop ingenious, sometimes even diabolical, techniques in order to deceive the subject about the true purposes of an investigation (see Stricker, 1967; Stricker, Messick, and Jackson, 1967). Deception may not be the only, nor the best, way of dealing with certain issues, yet we must ask what special characteristic of our science makes it necessary to even consider such techniques when no such need arises in, say, physics. The reason is plain: we do not study passive physical particles

*The substantive work reported in this paper was supported in part by Contract #Nonr 4731 from the Group Psychology Branch, Office of Naval Research. The research on the detection of deception was supported in part by the United States Army Medical Research and Development Command Contract #DA-49-193-MD-2647.

† I wish to thank Frederick J. Evans, Charles H. Holland, Edgar P. Nace, Ulric Neisser, Donald N. O'Connell, Emily Carota Orne, David A. Paskewitz, Campbell W. Perry, Karl Rickels, David L. Rosenhan, Robert Rosenthal, and Ralph Rosnow for their thoughtful criticisms and many helpful suggestions in the preparation of this manuscript.

143

144 MARTIN T. ORNE

but active, thinking human beings like ourselves. The fear that knowledge of the true purposes of an experiment might vitiate its results stems from a tacit recognition that the subject is not a passive responder to stimuli and experimental conditions. Instead, he is an active participant in a special form of socially defined interaction which we call "taking part in an experiment."

It has been pointed out by Criswell (1958), Festinger (1957), Mills (1961), Rosenberg (1965), Wishner (1965) and others, and discussed at some length by the author elsewhere (Orne, 1959b; 1962), that subjects are never neutral toward an experiment. While, from the investigator's point of view, the experiment is seen as permitting the controlled study of an individual's reaction to specific stimuli, the situation tends to be perceived quite differently by his subjects. Because subjects are active, sentient beings, they do not respond to the specific experimental stimuli with which they are confronted as isolated events but rather they perceive these in the total context of the experimental situation. Their understanding of the situation is based upon a great deal of knowledge about the kind of realities under which scientific research is conducted, its aims and purposes, and, in some vague way, the kind of findings which might emerge from their participation and their responses. The response to any specific set of stimuli, then, is a function of both the stimulus and the subject's recognition of the total context. Under some circumstances, the subject's awareness of the implicit aspects of the psychological experiment may become the principal determinant of his behavior. For example, in one study an attempt was made to devise a tedious and intentionally meaningless task. Regardless of the nature of the request and its apparently obvious triviality, subjects continued to comply, even when they were required to perform work and to destroy the product. Though it was apparently impossible for the experimenter to know how well they did, subjects continued to perform at a high rate of speed and accuracy over a long period of time. They ascribed (correctly, of course) a sensible motive to the experimenter and meaning to the procedure. While they could not fathom how this might be accomplished, they also quite correctly assumed that the experimenter could and would check their performance* (Orne, 1962). Again, in another study subjects were required to carry out such obviously dangerous activities as picking up a poisonous snake or removing a penny from fuming nitric acid with their bare hands (Orne and Evans, 1965). Subjects complied, correctly surmising that, despite appearances to the contrary, appropriate precautions for their safety had been taken.

145 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

In less dramatic ways the subject's recognition that he is not merely responding to a set of stimuli but is doing so in order to produce data may exert an influence upon his performance. Inevitably he will wish to produce "good" data, that is, data characteristic of a "good" subject. To be a "good" subject may mean many things: to give the right responses, i.e., to give the kind of response characteristic of intelligent subjects; to give the normal response, i.e., characteristic of healthy subjects; to give a response in keeping with the individual's self-perception, etc., etc. If the experimental task is such that the subject sees himself as being evaluated he will tend to behave in such a way as to make himself look good. (The potential importance of this factor has been emphasized by Rosenberg, 1965; see Chapter 7.)

Investigators have tended to be intuitively aware of this problem and in most experimental situations tasks are constructed so as to be ambiguous to the subject regarding how any particular behavior might make him look especially good. In some studies investigators have explicitly utilized subjects' concern with the evaluation in order to maximize motivation. However, when the subject's wish to look good is not directly challenged, another set of motives, one of the common bases for volunteering, will become relevant. That is, beyond idiosyncratic reasons for participating, subjects volunteer, in part at least, to further human knowledge, to help provide a better understanding of mental processes that ultimately might be useful for treatment, to contribute to science, etc. This wish which, despite currently fashionable cynicism, is fortunately still the mode rather than the exception among college student volunteers, has important consequences for the subject's behavior. Thus, in order for the subject to see the data as useful, it is essential that he assume that the experiment be important, meaningful, and properly executed. Also, he would hope that the experiment work, which tends to mean that it prove what it attempts to prove. Reasons such as these may help to clarify why subjects are so committed to see a logical purpose in what would otherwise appear to be a trivial experiment, why they are so anxious to ascribe competence to the experimenter and, at the end of a study, are so concerned that their data prove useful. The same set of motives also helps to understand why subjects often will go to considerable trouble and tolerate great inconvenience provided they are encouraged to see the experiment as important. Typically they will tolerate even intense discomfort if it seems essential to the experiment; on the other hand, they respond badly indeed to discomfort which they recognize as due to the experimenter's ineptness, incompetence, or indifference. Regardless of the extent to which they are reimbursed, most subjects will be thoroughly alienated if it becomes apparent that,

146 MARTIN T. ORNE

for one reason or another, their experimental performance must be discarded as data. Interestingly, they will tend to become angry if this is due to equipment failure or an error on the part of the experimenter, whereas if they feel that they themselves are responsible, they tend to be disturbed rather than angry.

The individual's concern about the extent to which the experiment helps demonstrate that which the experimenter is attempting to demonstrate will, in part, be a function of the amount of involvement with the experimental situation. The more the study demands of him, the more discomfort, the more time, the more effort he puts into it, the more he will be concerned about its outcome. The student in a class asked to fill out a questionnaire will be less involved than the volunteer who stays after class, who will in turn be less involved than the volunteer who is required to go some distance, who will in turn be less involved than the volunteer who is required to come back many times, etc., etc.*

Insofar as the subject cares about the outcome, his perception of his role and of the hypothesis being tested will become a significant determinant of his behavior. The cues which govern his perception -- which communicate what is expected of him and what the experimenter hopes to find -- can therefore be crucial variables. Some time ago I proposed that these cues be called the "demand characteristics of an experiment" (Orne, 1959b). They include the scuttlebutt about the experiment, its setting, implicit and explicit instructions, the person of the experimenter, subtle cues provided by him, and, of particular importance, the experimental procedure itself. All of these cues are interpreted in the light of the subject's past learning and experience. Although the explicit instructions are important, it appears that subtler cues from which the subject can draw covert or even unconscious inference may be still more powerful.

Recognizing that the subject's knowledge affects his performance, investigators have employed various means to disguise the true purpose of the research, thereby trying to alter the demand characteristics of experimental situations in order to make them orthogonal to the experimental effects. Unfortunately, the mere fact that an investigator goes to great lengths to develop a "cute" way to deceive the subject in no way guarantees that the subject is, in fact, deceived. Obviously it is

147 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

essential to establish whether the subject or the experimenter is the one who is deceived by the experimental manipulation.

I. DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND EXPERIMENTER BIAS

Demand characteristics and the subject's reaction to them are, of course, not the only subtle and human factors which may affect the results of an experiment. Experimenter bias effects, which have been studied in such an elegant fashion by Rosenthal (1963; 1966), also are frequently confounding variables. Experimenter bias effects depend in large part on experimenter outcome expectations and hopes. They can become significant determinants of data by causing subtle but systematic differences in (a) the treatment of subjects, (b) the selection of cases, (c) observation of data, (d) the recording of data, and (e) systematic errors in the analysis of data.

To the extent that bias effects cause subtle changes in the way the experimenter treats different groups, they may alter the demand characteristics for those groups. In social psychological studies, demand characteristics may, therefore, be one of the important ways in which experimenter bias is mediated. Conceptually, however, the two processes are very different. Experimenter bias effects are rooted in the motives of the experimenter, but demand characteristic effects depend on the perception of the subject.

The effects of bias are by no means restricted to the treatment of subjects. They may equally well function in the recording of data and its analysis. As Rosenthal (1966) has pointed out, they can readily be demonstrated in all aspects of scientific endeavor -- "N rays" being a prime example. Demand characteristics, on the other hand, are a problem only when we are studying sentient and motivated organisms. Light rays do not guess the purpose of the experiment and adapt themselves to it, but subjects may.

The repetition of an experiment by another investigator with different outcome orientation will, if the findings were due to experimenter bias, lead to different results. This procedure, however, may not be sufficient to clarify the effects of demand characteristics. Here it is the leanings of the subject, not of the experimenter, that are involved. In a real sense, for the subject an experiment is a problem-solving situation. Riecken (1962, 31) has succinctly expressed this when he says that aspects of the experimental situation lead to "a set of inferential and interpretive activities on the part of the subject in an effort to penetrate the experimenter's

148 MARTIN T. ORNE

inscrutability...." For example, if subjects are used as their own controls, they may easily recognize that differential treatment ought to produce differential results, and they may act accordingly. A similar effect may appear even when subjects are not their own controls. Those who see themselves as controls may on that account behave differently from those who think of themselves as the "experimentals."

It is not conscious deception by the subject which poses the problem here. That occurs only rarely. Demand characteristics usually operate subtly in interaction with other experimental variables. They change the subject's behavior in such a way that he is often not clearly aware of their effect. In fact, demand characteristics may be less effective or even have a paradoxical action if they are too obvious. With the constellation of motives that the usual subject brings to a psychological experiment, the "soft sell" works better than the "hard sell." Rosenthal (1963) has reported a similar finding in experimenter bias: the effect is weakened, or even reversed, if the experimenter is paid extra to bias his results.

It is possible to eliminate the experimenter entirely, as has been suggested by Charles Slack* some years back in a Gedanken experiment. He proposed that subjects be contacted by mail, be asked to report to a specific room at a specific time, and be given all instructions in a written form. The recording of all responses as well as the reinforcement of subjects would be done mechanically. This procedure would go a long way toward controlling experimenter bias. Nevertheless, it would have demand characteristics, as would any other experiment which we might conceive; subjects will always be in a position to form hypotheses about the purpose of an experiment.

Although every experiment has its own demand characteristics, these do not necessarily have an important effect on the outcome. They become important only when they interact with the effect of the independent variable being studied. Of course, the most serious situation is one where the investigator hopes to draw inferences from an experiment where one set of demand characteristics typically operates to a real life situation which lacks an analogous set of conditions.

II. PRE-INQUIRY DATA AS A BASIS FOR MANIPULATING DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS

A recent psychophysiological study (Gustafson and Orne, 1965) takes one possible approach to the clarification of demand characteristic

149 DEMAND CHARACTERISICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

effects. The example is unusual only because some of its demands were deliberately manipulated and treated as experimental variables in their own right. The results of the explicit manipulation enabled us to understand an experimental result which was otherwise contrary to field findings.

In recent years there have been a number of studies on the detection of deception -- more popularly known as "lie detection" -- with the galvanic skin response (GSR) as the dependent variable. In one such study, Ellson, Davis, Saltzman, and Burke (1952) reported a very curious finding. Their experiment dealt with the effect which knowledge of results can have on the GSR. After the first trial, some subjects were told that their lies had been detected, while others were told the opposite. This produced striking results on the second trial: those who believed that they had been found out became harder to detect the second time, while those who thought they had deceived the polygraph on Trial 1 became easier to detect on Trial 2. This finding, if generalizable to the field, would have considerable practical implications. Traditionally, interrogators using field lie detectors go to great lengths to show the suspect that the device works by "catching" the suspect, as it were. If the results of Ellson et al. were generalizable to the field situation, the very procedure which the interrogators use would actually defeat the purpose for which it was intended by making subsequent lies of the suspect even harder to detect.

Because the finding of Ellson et al. runs counter to traditional practical experience, it seemed plausible to assume that additional variables might be involved in the experimental situation. The study by Ellson et al. was therefore replicated by Gustafson and Orne* with equivocal results. Postexperimental interviews with subjects revealed that many college students apparently believe that the lie detector works with normal individuals and that only habitual liars could deceive a polygraph. Given these beliefs, it was important for the student volunteers that they be detected. In that respect the situation of the experimental subjects differs markedly from that of the suspect being interrogated in a real life situation. Fortunately, with the information about what most experimental subjects believe, it is possible to manipulate these beliefs and thereby change the demand characteristics of the Ellson et al. study. Two groups of subjects were given different information about the effectiveness of the lie detector.

One group was given information congruent with this widely held belief and told: "This is a detection of deception experiment. We are trying to see how well the lie detector works. As you know, it is not

150 MARTIN T. ORNE

possible to detect lying in the case of psychopathic personalities or habitual liars. We want you to try your very best to fool the lie detector during this experiment. Good luck." These instructions tried to maximize the kind of demand characteristics which might have been functioning in the Ellson et al. study, and it was assumed that the subjects would want to be detected in order to prove that they were not habitual liars. The other group was given information which prior work (Gustafson and Orne, 1963) had shown to be plausible and motivating; they were told, "This is a lie detection study and while it is extremely difficult to fool the lie detector, highly intelligent, emotionally stable, and mature individuals are able to do so." The demand characteristics in this case were designed to maximize the wish to deceive.

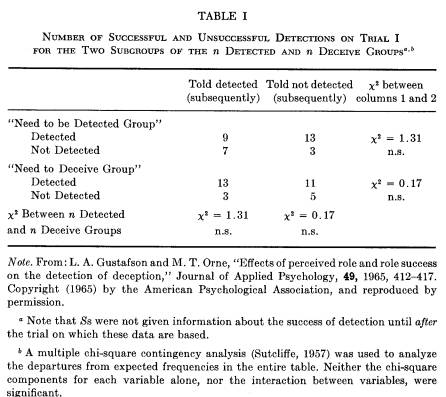

From that point on, the two groups were treated identically. They drew a card from an apparently randomized deck; the card had a number on it which they were to keep secret. All possible numbers were then presented by a prerecorded tape while a polygraph recorded the subjects' GSR responses. On the first such trial, the "detection ratios" -- that is, the relative magnitudes of the critical GSR responses -- in the two groups were not significantly different (see Table I). When the first trial was over, the experimenter gave half the subjects in each group the impression that they had been detected, by telling them what their number had been. (The experimenter had independent access to this information.) The other half were given the impression that they had fooled the polygraph, the experimenter reporting an incorrect number to them. A table of random numbers was used to determine, independent of his actual GSR, which kind of feedback each subject received.

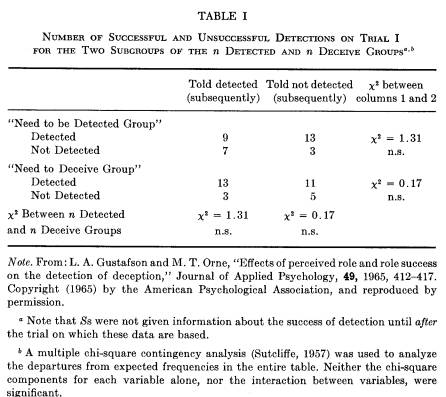

A second detection trial with a new number was then given. The dramatic effects of the feedback in interaction with the original instructions are visible in Table II. Two kinds of subjects now gave large GSRs to the critical number: those who had wanted to be detected but yet had not been detected, and also those who had hoped to deceive and yet had not deceived. (This latter group is analogous to the field situation.) On the other hand, subjects whose hopes had been confirmed now responded less and thus became harder to detect, regardless of what those hopes had been. Those who had wanted to be detected, and indeed had been detected, behaved physiologically like those who had wanted to deceive and indeed had deceived.

This effect is an extremely powerful but also an exceedingly subtle one. The differential pretreatment of groups is not apparent on the first trial. Only on the second trial do the manipulated demand characteristics produce clear-cut differential results, in interaction with the independent variable of feedback. Furthermore, we are dealing with a dependent

151 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

measure which is often erroneously assumed to be outside of volitional control, namely a physiological response -- in this instance, the GSR. This study serves as a link toward resolving the discrepancy between the laboratory findings of Ellson et al. (1952) and the experience of interrogators using the "lie detector" in real life.

It appeared possible in this experiment to use simple variations in instructions as a means of varying demand characteristics. The success

of the manipulation may be ascribed to the fact that the instructions themselves reflected views that emerged from interview data, and both sets of instructions were congruent with the experimental procedure. Only if instructions are plausible -- a function of their congruence with the subjects' past knowledge as well as with the experimental procedure -- will they be a reliable way of altering the demand characteristics. In this instance the instructions were not designed to manipulate the subjects' attitude directly; rather they were designed to provide differential background information relevant to the experiment. This background

152 MARTIN T. ORNE

information was designed to provide very different contexts for the subjects' performance within the experiment. We believe this approach was effective because it altered the subjects' perception of the experimental situation, which is the basis of demand characteristics in any experiment. It is relevant that the differential instructions in no way told subjects to behave differently. Obviously subjects in an experiment will tend to do what they are told to do -- that is the implicit contract of the situation -- and to demonstrate this would prove little. Our effort here

was to create the kind of context which might differentiate the laboratory from the field situation and which might explain differential results in these two concepts. Plausible verbal instructions were one way of accomplishing this end. (Also see Cataldo, Silverman, and Brown, 1967; Kroger, 1967; Page and Lumia, 1968; Silverman, 1968.)

Unless verbal instructions are very carefully designed and pretested they may well fail to achieve such an end. It can be extremely difficult to predict how, if at all, demand characteristics are altered by instructions, and frequently more subtle aspects of the experimental setting

153 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

and the experimental procedure may become more potent determinants of how the study is perceived.

III. DEALING WITH DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS

Studies such as the one described in which the demand characteristics are deliberately manipulated contribute little or nothing to the question of how they can be delineated. In order to design the lie detection experiment in the first place, a thorough understanding of the demand characteristics involved was essential. How can such an understanding be obtained? As was emphasized earlier, the problem arises basically because the human subject is an active organism and not a passive responder. For him, the experiment is a problem-solving situation to be actively handled in some way. To find out how he is trying to handle it, it has been found useful to take advantage of the same mental processes which would otherwise be confounding the data. Three techniques were proposed which do just that. Although apparently different, the three methods serve the same basic purpose. For reasons to be explained later, I propose to call them "quasi-controls."

A. Postexperimental Inquiry

The most obvious way of finding out something about the subject's perception of the experimental situation is the postexperimental inquiry. It never fails to amaze me that some colleagues go to the trouble of inducing human subjects to participate in their experiments and then squander the major difference between man and animal -- the ability to talk and reflect upon experience.

To be sure, inquiry is not always easy. The greatest danger is the "pact of ignorance" (Orne, 1959a) which all too commonly characterizes the postexperimental discussion. The subject knows that if he has "caught on" to some apparent deception and has an excess of information about the experimental procedure he may be disqualified from participation and thus have wasted his time. The experimenter is aware that the subject who knows too much or has "caught on" to his deception will have to be disqualified; disqualification means running yet another subject, still further delaying completion of his study. Hence, neither party to the inquiry wants to dig very deeply.

The investigator, aware of these problems and genuinely more interested in learning what his subjects experienced than in the rapid collection of data, can, however, learn a great deal about the demand characteristics of a particular experimental procedure by judicious inquiry.

154 MARTIN T. ORNE

It is essential that he elicit what the subject perceives the experiment is about, what the subject believes the investigator hopes and expects to find, how the subject thinks others might have reacted in this situation, etc. This information will help to reveal what the subject perceives to be a good response, good both in tending to validate the hypothesis of the experiment and in showing him off to his best advantage.

To the extent that the subject perceives the experiment as a problem-solving situation where the subject's task is to ascertain the experiment's true nature, the inquiry is directed toward clarifying the subject's beliefs about its true nature. When, as is often the case, the investigator will have told the subject in the beginning something about why the experiment is being carried out, it may well be difficult for the subject to express his disbelief since to do so might put him in the position of seeming to call the experimenter a liar. For reasons such as these, the postexperimental interview must be conducted with considerable tact and skill, creating a situation where the subject is able to communicate freely what he truly believes without, however, making him unduly suspicious or, worse yet, cueing him as to what he is to say. Using another investigator to carry out the inquiry will often maximize communication, particularly if the other investigator is seen as someone who is attempting to learn more about what the subject experiences. However, it is necessary to avoid having it appear as though the inquiry is carried out by someone who is evaluating the experimenter since the student subject may identify with what he sees to be the student experimenter and try to make him look good rather than describing his real experience. The situational factors which will maximize the subject's communicating what he is experiencing are clearly exceedingly complex and conceptually similar to those which need to be taken into account in clinical situations or in the study of taboo topics. Examples of the factors are merely touched upon here.

It would be unreasonable to expect a one-to-one relationship between the kind of data obtained by inquiry and the demand characteristics which were actually perceived by the subject in the situation. Not only do many factors mitigate against fully honest communication, but the subject cannot necessarily verbalize adequately what he may have dimly perceived during the experiment, and it is the dimly perceived factors which may exert the greatest effect on the subject's experimental behaviors. More important than any of these considerations, however, is the fact that an inquiry may be carried out at the end of a complex experiment and that the subject's perception of the experiment's demand characteristics may have changed considerably during the experiment. For example, a subject might "catch on" to a verbal conditioning experiment only

155 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

at the very end or even in retrospect during the inquiry itself, and he may then verbalize during the inquiry an awareness that will have had little or no effect on his performance during the experiment. For this reason, one may wish to carry out inquiry procedures at significant junctures in a long experiment.* This technique is quite expensive and time-consuming. It requires running different sets of subjects to different points in the experiment, stopping at these points as if the experiment were over (for these subjects it, in fact, is), and carrying out inquiries. While it would be tempting to use the same group of subjects and to continue to run them after the inquiry procedure, such a technique would in many instances be undesirable because exhaustive inquiries into the demand characteristics, as the subject perceives them at a given point in time, make him unduly aware of such factors subsequently.

While inquiry procedures may appear time-consuming, in actual practice they are relatively straightforward and efficient. Certainly they are vastly preferable to finding at the conclusion of a large study that the data depend more on the demand characteristics than on the independent variables one had hoped to investigate. It is perhaps worth remembering that, investigators being human, it is far easier to do exhaustive inquiry during pilot studies when one is still motivated to find out what is really happening than in the late stages of a major investigation. Indeed this is one of the reasons why pilot investigations are an essential prelude to any substantive study.

B. Non-experiment

Another technique -- and a very powerful one -- for uncovering the demand characteristics of a given experimental design is the "pre-inquiry" (Orne, 1959a) or the "non-experiment."† This procedure was independently proposed by Riecken (1962). A group of persons representing the same population from which the actual experimental subjects will eventually be selected are asked to imagine that they are subjects themselves. They are shown the equipment that is to be used and the room in which the experiment is to be conducted. The procedures are explained in such a way as to provide them with information equivalent to that which would be available to an experimental subject. However, they do not actually go through the experimental procedure; it is only explained. In a non-experiment on a certain drug, for example, the participant would be told that subjects are given a pill. He would be shown the pill. The instructions destined for the experimental subjects would

† Ulric Neisser suggested this persuasive term.

156 MARTIN T. ORNE

be read to him. The participant would then be asked to produce data as if he actually had been subjected to the experimental treatment. He could be given posttests or asked to fill out rating scales or requested to carry out any behavior that might be relevant for the actual experimental group.

The non-experiment yields data similar in quality to inquiry material but obtained in the same form as actual subjects' data. Direct comparison of non-experimental data and actual experimental data is therefore possible. But caution is needed. If these two kinds of data are identical, it shows only that the subject population in the actual experiment could have guessed what was expected of them. It does not tell us whether such guesses were the actual determinants of their behavior.

Kelman (1965) has recently suggested that such a technique might appropriately be used as a social psychological tool to obviate the need for deception studies. While the economy of this procedure is appealing, and working in a situation where subjects become quasi-collaborators instead of objects to be manipulated is more satisfying to many of us, it would seem dangerous to draw inferences to the actual situation in real life from results obtained in this fashion. In fact, when subjects in pre-inquiry experiments perform exactly as subjects do in actual experimental situations, it becomes impossible to know the extent to which their performance is due to the independent variables or to the experimental situation.

In most psychological studies, when one is investigating the effect of the subject's best possible performance in response to different physical or psychological stimuli, there is relatively little concern for the kind of problems introduced by demand characteristics. The need to concern oneself with these issues becomes far more pronounced when investigating the effect of various interventions such as drugs, psychotherapy, hypnosis, sensory deprivation, conditioning of physiological responses, etc., on performance or experiential parameters. Here the possibility that the subject's response may inadvertently be determined by altered demand characteristics rather than the process itself must be considered. Equally subject to these problems are studies where attitude changes rather than performance changes are explored. The investigator's intuitive recognition that subjects' perceptions of an experiment and its meaning are very likely to affect the nature of his responses may have been one of the main reasons why deception studies have been so popular in the investigation of attitude change.

Festinger's cognitive dissonance theory (1957) has been particularly attractive to psychologists probably because it makes predictions which

157 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

appear to be counterexpectational; that is, the predictions made on the basis of intuitive "common sense" appear to be wrong whereas those made on the basis of dissonance are both different and borne out by data. Bem (1967) has shown in an elegant application of pre-inquiry techniques that the findings are not truly counterexpectational in the sense that subjects to whom the situation is described in detail but who are not really placed in the situation are able to produce data closely resembling those observed in typical cognitive dissonance studies. On the basis of these findings, Bern (1967) appropriately questions the assertion that the dissonance theory allows counterexpectational predictions. His use of the pre-inquiry effectively makes the cognitive dissonance studies it replicates far less compelling by showing that subjects could figure out the way others might respond. It would be unfortunate to assume that Bem's incisive critique of the empirical studies with the pre-inquiry technique makes further such studies unnecessary. On the contrary, his findings merely show that the avowed claims of these studies were not, in fact, achieved and provide a more stringent test for future experiments that aim to demonstrate counterexpectational findings.

It would appear that we are in the process of completing a cycle. At one time it was assumed that subjects could predict their own behavior, that in order to know what an individual would do in a given situation it would suffice merely to ask him. It became clear, however, that individuals could not always predict their behavior; in fact, serious questions about the extent to which they could make any such predictions were raised when studies showing differences between what individuals thought they do and what they, in fact, do became fashionable. With a sophisticated use of the pre-inquiry technique Bem (1967) has shown that individuals have more knowledge about what they might do than has been ascribed to them by psychologists. Although it is possible to account for a good deal of variance in behavior in this way, it is clear that it will not account for all of the variance. We are confronted now with a peculiar paradox. When pre-inquiry data correctly predict the performance of the subject in the actual experiment--the situation that is most commonly encountered -- the experimental findings strike us as relatively trivial, in part because at best we have validated our intuitive common sense but also because we cannot exclude the nagging doubt that the subject may have merely been responsive to the demand characteristics in the actual experiment. Only when we succeed in setting up an experiment where the results are counterexpectational in the sense that a pre-inquiry would yield different findings from those obtained from the subjects in the actual situation can we

158 MARTIN T. ORNE

be relatively comfortable that these findings represent the real effects of the experimental treatment rather than being subject to alternative explanations.

For the reasons discussed above, pre-inquiry can never supplant the actual investigation of what subjects do in concrete situations although, adroitly executed, it becomes an essential tool to clarify these findings.

C. Simulators

This principle can be carried one step further to provide yet another method for uncovering demand characteristics: the use of simulators (Orne, 1959a). Subjects are asked to pretend that they have been affected by an experimental treatment which they did not actually receive or to which they are immune. For subjects to be able to do this, it is crucial that they be run by another experimenter who they are told is unaware of their actual status, and who in fact really is unaware of their status. It is essential that the subjects be aware that the experimenter is blind as well as that the experimenter actually be blind for this technique to be effective. Further, the fact that the experimenter is "blind" has the added advantage of forcing him to treat simulators and actual subjects alike. This technique has been used extensively in the study of hypnosis (e.g., Damaser, Shor, and Orne, 1963; Orne, 1959a; Orne and Evans, 1965; Orne, Sheehan, and Evans, 1968). For an extended discussion, see Orne (1968). It is possible for unhypnotized subjects to deceive an experimenter by acting as though they had been hypnotized. Obviously, it is essential that the simulators be given no special training relevant to the variables being studied, so that they have no more information than what is available to actually hypnotized subjects. The simulating subjects must try to guess what real subjects might do in a given experimental situation in response to instructions administered by a particular experimenter.

This design permits us to separate experimenter bias effects from demand characteristic effects. In addition to his other functions, the experimenter may be asked to judge whether each subject is a "real" or a simulator. This judgment tends to be random and unrelated to the true status of the subjects. Nevertheless, we have often found differences between the behaviors of subjects contingent on whether or not the experimenter judges that they are hypnotized or just simulating. Such differences may be ascribed to differential treatment and bias, whereas differences between actually hypnotized subjects and actual simulators are likely to be due to hypnosis itself.

Again, results obtained with this technique need careful evaluation. It is important not to jump to a negative conclusion if no difference

159 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

is found between deeply hypnotized subjects and simulators. Such data are not evidence that hypnosis consists only of a reaction to demand characteristics. It may well have special properties. But so long as a given form of behavior is displayed as readily by simulators as by "reals," our procedure has failed to demonstrate those properties. The problem here is the same as that discussed earlier in the pre-inquiry. Most likely there will be many real effects due to hypnosis which can be mimicked successfully by simulators. However, only when we are able to demonstrate differences in behavior between real and simulating subjects do we feel that an experiment is persuasive in demonstrating that a given effect is likely to be due to the presence of hypnosis.

IV. QUASI-CONTROLS: TECHNIQUES FOR THE EVALUATION OF EXPERIMENTAL ROLE DEMANDS

The three techniques discussed above are not like the usual control groups in psychological research. They ask the subject to participate actively in uncovering explicit information about possible demand characteristic effects. The quasi-control subject steps out of his traditional role, because the experimenter redefines the interaction between them to make him a co-investigator instead of a manipulated object. Because the quasi-control is outside of the usual experimenter-subject relationship, he can reveal the effects of this relationship in a new perspective. An inquiry, for example, takes place only after the experiment has been defined as "finished," and the subject joins the experimenter in reflecting on his own earlier performance as a subject. In the non-experiment, the quasi-control cooperates with the experimenter in second-guessing what real subjects might do. Most dramatically, the simulating subject reverses the usual relationship and deceives the experimenter.

It is difficult to find an appropriate term for these procedures. They are not, of course, classical control groups since, rather than merely omitting the independent variable, the groups are treated differently. Thus we are dealing with treatment groups that facilitate inference about the behavior of both experimental and control groups. Because these treatment groups are used to assess the effect that the subject's perception of being under study might have upon his behavior in the experimental situation, they may be conceptualized as role demand controls in that they clarify the demand characteristic variables in the experimental situation for the particular subject population used. As quasi-controls, the subjects are required to participate and utilize their cognitive processes to evaluate the possible effect that thinking about the total situa-

160 MARTIN T. ORNE

tion might have on their performance. They could, in this sense, be considered active, as opposed to passive, controls.

A unique aspect of quasi-controls is that they do not permit inference to be drawn about the effect of the independent variable. They can never prove that a given finding in the experimental group is due to the demand characteristics of the situation. Rather, they serve to suggest alternative explanations not excluded by the experimental design employed. The inference from quasi-control data, therefore, primarily concerns the adequacy of the experimental procedure. In this sense, the term design control or evaluative control would be justified.

Since each of these various terms focuses upon different but equally important aspects of these comparison groups, it would seem best to refer to them simply as quasi-controls. This explicitly recognizes that we are not dealing with control groups in the true sense of the word and are using the term analogously to the way in which Campbell and Stanley (1963) have used the term quasi-experiments. However, while they think of quasi-experiments as doing the best one can in situations where "true experiments" cannot be carried out, the concept of quasi-controls is intended to refer specifically to techniques for the assessment of demand characteristic variables in order to evaluate how such factors might effect the experimental outcome. The term "quasi-" in this context says that these techniques are similar to -- but not really -- control groups. It does not mean that these groups are any less important in helping to evaluate the data obtained from human subjects. In bridging the gap from the laboratory experiments to situations where the individual does not perceive himself to be a subject under investigation, techniques of this kind are of vital importance.

It is frequently pointed out that investigators often discuss the experimental procedures with colleagues in order to clarify their meaning. Certainly many problems in experimental design will be obvious only to expert colleagues. These types of issues have typically been discussed in the context of quantitative methods and have led to some more elaborate techniques of experimental design. There is no question that expert colleagues are sensitive to order effects, baseline phenomena, practice effects, sampling procedures, individual differences, and so on, but how a given subject population would, in fact, perceive an experimental procedure is by no means easily accessible to the usual tools of the psychologists. Whether in a deception experiment the subject may be partially or fully aware of what is really going on is a function of a great many cues in the situation not easily explicated, and the prior experience of the subject population which might in some way be relevant to the experiment is also not easily ascertained or abstracted by any amount

161 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

of expert discussion. The use of quasi-controls, however, allows the investigator to estimate these factors and how they might affect the experimental results.

The kind of factors which we are discussing here relate to the manner in which subjects are solicited (for example, the wording of an announcement in an ad), the manner in which the secretary or research assistant answers questions about the proposed experiment when subjects call in to volunteer, the location of the experiment (i.e., psychiatric hospital versus aviation training school), and, finally, a great many details of the experimental procedure itself which of necessity are simplified in the description, not to speak of the subtle cues made available by the investigator himself. Quasi-controls are designed to evaluate the total impact of these various cues upon the particular kind of population which is to be used. It will be obvious, of course, that a verbal conditioning experiment carried out with psychology students who have been exposed to the original paper is by no means the same as the identical experiment carried out with students who have not been exposed to this information. Again, quasi-controls allow one to estimate what the demand characteristics might be for the particular subject population being used.

Quasi-controls serve to clarify the demand characteristics but they can never yield substantive data. They cannot even prove that a given result is a function of demand characteristics. They provide information about the adequacy of an investigative procedure and thereby permit the design of a better one. No data are free of demand characteristics but quasi-controls make it possible to estimate their effect on the data which we do obtain.

V. THE USE OF QUASI-CONTROLS TO MAKE POSSIBLE A STUDY MANIPULATING DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS

When extreme variations of experimental procedures are still able to elicit surprisingly similar results or identical experimental procedures carried out in different laboratories yield radically different results, the likelihood of demand characteristic effects must be seriously considered. An area of investigation characterized in this way were the early studies on "sensory deprivation." The initial findings attracted wide attention because they not only had great theoretical significance for psychology but seemed to have practical implications for the space program as well. A review of the literature indicated that dramatic hallucinatory effects and other perceptual changes were typically observed after the subject had been in the experiment approximately two-thirds of the

162 MARTIN T. ORNE

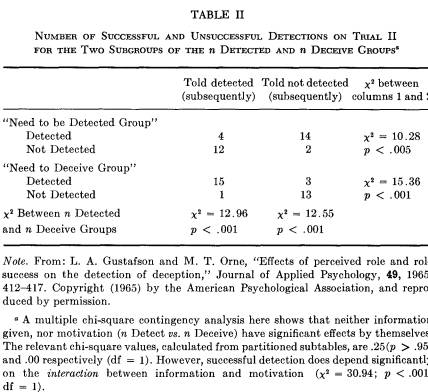

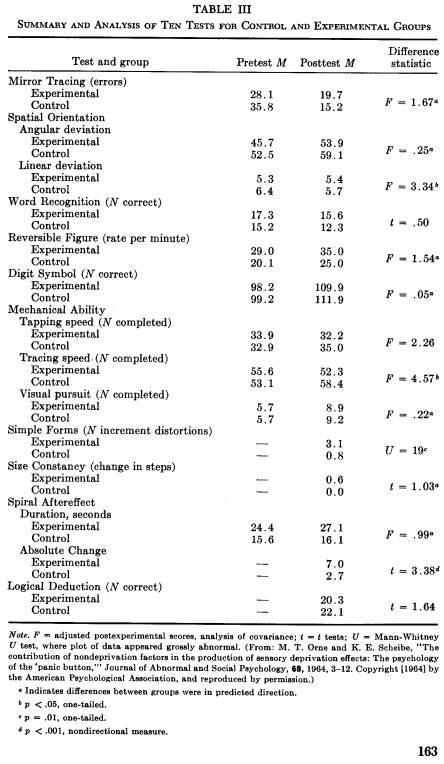

total time; however, it seemed to matter relatively little whether the total time was three weeks, two weeks, three days, two days, twenty-four hours, or eight hours. Clearly, factors other than physical conditions would have to account for such discrepancies. As a first quasi-control we interviewed subjects who had participated in such studies.* It became clear that they had been aware of the kind of behavior that was expected of them. Next, a pre-inquiry was carried out, and, from participants who were guessing how they might respond if they were in a sensory deprivation situation, we obtained data remarkably like that observed in actual studies.† We were then in a position to design an actual experiment in which the demand characteristics of sensory deprivation were the independent variables (Orne and Scheibe, 1964). Our results showed that these characteristics, by themselves, could produce many of the findings attributed to the condition of sensory deprivation. In brief, one group of the subjects were run in a "meaning deprivation" study which included the accoutrements of sensory deprivation research but omitted the condition itself. They were required to undergo a physical examination, provide a short medical history, sign a release form, were "assured" of the safety of the procedure by the presence of an emergency tray containing various syringes and emergency drugs, and were taken to a well-lighted cubicle, provided food and water, and given an optional task. After taking a number of pretests, the subjects were told that if they heard, saw, smelled, or experienced anything strange they were to report it through the microphone in the room. They were again reassured and told that if they could not stand the situation any longer or became discomforted they merely had to press the red "panic button" in order to obtain immediate release.

They were then subjected to four hours of isolation in the experimental cubicle and given posttests. The control subjects were told that they were controls for a sensory deprivation study and put in the same objective conditions as the experimental subjects. Table III summarizes the findings which indicate that manipulation of the demand characteristics by themselves could produce many findings that had previously been ascribed to the sensory deprivation condition. Of course, neither the quasi-controls nor the experimental manipulation of the demand characteristics sheds light on the actual effects of the condition of sensory deprivation. They do show that demand characteristics may produce similar effects to those ascribed to sensory deprivation.

† Stare, F., Brown, J., and Orne, M. T. Demand characteristics in sensory deprivation studies. Unpublished seminar paper, Massachusetts Mental Health Center and Harvard University, 1959.

163 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

164 MARTIN T. ORNE

VI. THE PROBLEM OF INFERENCE

Great care must be taken in drawing conclusions from experiments of this kind. In the case of the sensory deprivation study, the demand characteristics of the laboratory and those which might be encountered by individuals outside of the laboratory differ radically. In other situations, however, such as in the case of hypnosis, the expectations of subjects about the kind of behavior hypnosis ought to elicit in the laboratory are similar to the kind of expectations which patients might have about being hypnotized for therapeutic purposes. To the extent that the hypnotized individual's behavior is determined by these expectations we might find similar findings in certain laboratory contexts and certain therapeutic situations. When demand characteristics become a significant determinant of behavior, valid accurate predictions can only be made about another situation where the same kind of demand characteristics prevails. In the case of sensory deprivation studies, accurate predictions would therefore not be possible but, even in the studies with hypnosis, we might still be observing an epiphenomenon which is present only as long as consistent and stable expectations and beliefs are present. In order to get beyond such an epiphenomenon and find intrinsic characteristics, it is essential that we evaluate the effect that demand characteristics may have. To do this we must seek techniques specifically designed to estimate the likely extent of such effects.

VII . PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGICAL RESEARCH AS A MODEL FOR THE PSYCHOLOGICAL EXPERIMENT

What are here termed the demand characteristics of the experimental situation are closely related to what the psychopharmacologist considers a placebo effect, broadly defined. The difficulty in determining what aspects of a subject's performance may legitimately be ascribed to the independent variable as opposed to those which might be due to the demand characteristics of the situation is similar to the problem of determining what aspects of a drug's action are due to pharmacological effect and what aspects are due to the subject's awareness that he has been given a drug. Perhaps because the conceptual distinction between a drug effect and the effect of psychological factors is readily made, perhaps because of the relative ease with which placebo controls may be included, or most likely because of the very significant consequences of psychopharmacological research, considerable effort has gone into

165 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

differentiating pharmacological action from placebo effects. A brief review of relevant observations from this field may help clarify the problem of demand characteristics.

In evaluating the effect of a drug it has long been recognized that a patient's expectations and beliefs may have profound effects on his experiences subsequent to the taking of the drug. It is for this reason that the use of placebos has been widespread. The extent of the placebo effect is remarkable. Beecher (1959), for example, has shown that in battlefield situations saline solution by injection has 90 per cent of the effectiveness of morphine in alleviating the pain associated with acute injury. In civilian hospitals, postoperatively, the placebo effect drops to 70 per cent of the effectiveness of morphine, and with subsequent administrations drops still lower. These studies show not only that the placebo effect may be extremely powerful, but that it will interact with the experimental situation in which it is being investigated.

It soon became clear that it was not sufficient to use placebos so long as the investigator knew to which group a given individual belonged. Typically, when a new, presumably powerful, perhaps even dangerous medication is administered, the physician takes additional care in watching over the patient. He tends to be not only particularly hopeful but also particularly concerned. Special precautions are instituted, nursing care and supervision are increased, and other changes in the regime inevitably accompany the drug's administration. When a patient is on placebo, even if an attempt is made to keep the conditions the same, there is a tendency to be perfunctory with special precautions, to be more cavalier with the patient's complaints, and in general to be less concerned and interested in the placebo group. For these reasons, the doctor, as well as the patient, is required to be blind as to the true nature of a drug; otherwise differential treatment could well account for some of the observed differences between drug and placebo (Modell and Houde, 1958). The problems discussed here would be conceptualized in social psychological terms as E-bias effects or differential E-outcome expectations.

What would appear at first sight to be a simple problem -- to determine the pharmacological action of a drug as opposed to those effects which may be attributed to the patient's awareness that he is being treated by presumably effective medication -- turns out to be extremely difficult. Indeed, as Ross, Krugman, Lyerly, and Clyde (1962) have pointed out, and as discussed by Lana (Chapter 4), the usual clinical techniques can never evaluate the true pharmacological action of a drug. In practice, patients are given a drug and realize that they are being treated; therefore one always observes the pharmacological action of the drug con-

166 MARTIN T. ORNE

founded with the placebo effect. The typical study with placebo controls compares the effect of placebo and drug versus the effect of placebo alone. Such a procedure does not get at the psychopharmacological action of the drug without the placebo effect, i.e., the patient's awareness that he is receiving a drug. Ross et al. elegantly demonstrate this point by studying the effect of chloral hydrate and amphetamine in a 3 X 3 design. Amphetamine, chloral hydrate, and placebo were used as three agents with three different instructions: (a) administering each capsule with a brief description of the amphetamine effect, (b) administering each capsule with a brief description of the chloral hydrate effect, and (c) administration without the individual's awareness that a drug was being administered. Their data clearly demonstrate that drug effects interact with the individual's knowledge that a drug is being administered.

For clinical psychopharmacology, the issues raised by Ross et al. are somewhat academic since in medical practice one is almost always dealing with combinations of placebo components and drug effects. Studies evaluating the effect of drugs are intended to draw inference about how drugs work in the context of medical practice. To the extent that one would be interested in the psychopharmacological effect as such -- that is, totally removed from the medical context -- the type of design Ross et al. utilized would be essential.

In psychology, experiments are carried out in order to determine the effect of an independent variable so that it will be possible to draw inference to non-experimental situations. Unfortunately the independent variables tend to be studied in situations that are explicitly defined as experimental. As a result, one observes the effect of an experimental context in interaction with a particular independent variable versus the effect of the experimental context without this variable.

The problem of the experimental context in which an investigation is carried out is perhaps best illustrated in psychopharmacology by research on the effects of meprobamate (known under the trade names of Equanil and Miltown). Meprobamate had been established as effective in a number of clinical studies but, when carefully controlled investigations were carried out, it did not appear to be more efficacious than placebo. The findings from carefully controlled studies appeared to contradict a large body of clinical observations which one might have a tendency to discount as simply due to placebo effect. It remained for Fisher, Cole, Rickels, and Uhlenhuth (1964) to design a systematic investigation to clarify this paradox, using physicians displaying either a "scientific," skeptical attitude toward medication or enthusiasm about the possible help which the drug would yield. The study was run double-

167 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

blind. The patients treated by physicians with a "scientific" attitude toward medication showed no difference between drug and placebo; however, those treated by enthusiastic physicians clearly demonstrated an increased effectiveness of meprobamate! It would appear that there is a "real" drug effect of meprobamate which may, however, be totally obscured by the manner in which the drug is administered. The effect of the drug emerges only when medication is administered with conviction and enthusiasm. The striking interaction between the drug effects and situation-specific factors not only points to limitations in conclusions drawn from double-blind studies in psychopharmacology but also has broad methodological implications for the experimental study of psychological processes. An example of these implications from an entirely different area is the psychotherapy study by Paul (1966) which showed differences in improvement between individuals expecting to be helped at some time in the future and a matched control group who were not aware that they were included in the research.

VIII. DEALING WITH THE PLACEBO EFFECT: AN ANALOGY TO DEALING WITH DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS

Drug effects that are independent of the patient's expectations, beliefs, and attitudes can of course be studied with impunity without concern about the psychological effects that may be attributed to the taking of medication. For example, the antipyretic fever-reducing effect of aspirin is less likely to be influenced by the patient's beliefs and expectations than is the analgesic effect, though even here an empirical approach is considerably safer than a priori assumptions.

Of greatest relevance are the psychological effects of drugs. The problems encountered in studying these effects, while analogous to those inherent in other kinds of psychological research, seem more evident here. Since the drug constitutes a tangible independent variable (subject to study by pharmacological techniques), it is conceptually easily distinguished from another set of independent variables, psychological in nature, that also may play a crucial part in determining the patient's response.

The totality of these non-drug effects which are a function of the patient's expectations and beliefs in interaction with the medical procedures that are carried out, the doctor's expectations, and the manner in which he is treated have been conceptualized as placebo effect. This is, of course, analogous to the demand characteristic components in psychological studies; the major difference is that the concept of placebo compo-

168 MARTIN T. ORNE

nent directly derives from methodological control procedures used to evaluate it.

The placebo is intended to produce the same attitudes, expectations, and beliefs of the patient as would the actual drug. The double-blind technique is designed to equate the environmental cues which would interact with these attitudes. For this model to work, it is essential that the placebo provide subjective side effects analogous to the actual drug lest the investigator and physician be blind but the patient fully cognizant that he is receiving a placebo. For these reasons an active placebo should be employed which mimics the side effects of the drug without exerting a central pharmacological action.

With the use of active placebos administered by physicians having appropriate clinical attitudes in a double-blind study a technically difficult but conceptually straightforward technique is available for the evaluation of the placebo effect. This approach satisfies the assumptions of the classical experimental model. One group of patients responds to the placebo effect and the drug, the other group to the placebo effect alone, which permits the investigator to determine the additive effect that may be attributed to the pharmacological action of the drug. Unfortunately such an ideal type of control is not generally available in the study of other kinds of independent variables. This is particularly true regarding the context of such studies. Thus, the placebo technique can be applied in clinical settings where the patient is not aware that he is the object of such study whereas psychological studies most frequently are recognized as such by our subjects who typically are asked to volunteer. Because a true analog to the placebo is not readily available, quasi-control techniques are being proposed to bridge the inferential gap between experimental findings and the influence of the experimental situation upon the subject who is aware that he is participating in an experiment.

The function of quasi-controls to determine the possible contextual effects of an experimental situation is perhaps clarified best when we contrast them with the use of placebos in evaluating possible placebo effect. Assume that we wish to evaluate an unknown drug purporting to be a powerful sedative and that neither pharmacological data nor placebo controls are available as methodological tools. All that we are able to do is to administer the drug under a variety of conditions and observe its effects. This is in many ways analogous to the kind of independent variable that we normally study in psychology. In fact, in this example the unknown drug will be sodium amytal, a powerful hypnotic with indisputable pharmacological action.

On giving the drug the first time, with considerable trepidation of

169 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

course, we might well observe relatively little effect. Then as we get used to the drug a bit we might see it causes relaxation, a lessening of control, perhaps even some slurring of speech; in fact, some of the kind of changes typically associated with alcohol.

At this point, working with relatively small dosages of the drug, we would find that there were wide individual differences in response, some individuals actually becoming hyperalert, and one might wonder to what extent the effects could be related to subjects' beliefs and expectations. Under these circumstances the inquiry procedures discussed earlier could be carried out after the drug had been given. One would focus the inquiry on what the subject feels the drug might do, the kind of side effects he might expect, what he anticipated he would experience subsequent to taking the drug, what he thought we would have expected to happen, what he believed others might have experienced after taking the drug, etc. Data of this kind might help shed light on the patient's behavior.

Putting aside the difficulty of interpreting inquiry material, and assuming we are capable of obtaining a good approximation of what the subject really perceived, we are still not in a position to determine the extent to which his expectations actually contributed to the effects that had been observed. Consider if a really large dose of amytal had been given: essentially all subjects would have gone to sleep and would most likely have correctly concluded they had been given a sleeping pill -- the inquiry data in this instance being the result of the observed effect rather than the cause of it. Inquiry data would become suggestive only if (in dealing with relatively small dosages) it were found that subjects who expected or perceived that we expected certain kinds of effects did in fact show these effects whereas subjects who had no such expectations failed to show the effects. Even if we obtained such data, however, it would still be unclear whether the subject's perceptions were post hoc or propter hoc. The most significant use of inquiry material would be in facilitating the recognition of those cues in the situation which might communicate what is expected to the subject so that these cues could be altered systematically. Neither subject nor investigator is really in a position to evaluate how much of the total effect may legitimately be ascribed to the placebo response and how much to drug effect. Evaluation becomes possible only after subsequent changes in procedure can be shown to eliminate certain effects even though the same drug is being administered, or, conversely, subjects' perceptions upon inquiry are changed without changing the observed effect. The approach then would be to compare the effect of the drug in interaction with different sets of demand characteristics in order to estimate how much of the

170 MARTIN T. ORNE

total effect can reasonably be ascribed to demand characteristic components. (The paper previously mentioned by Ross et al. [1962] reports precisely such a study with amytal and showed clear-cut differences.)

It is clear that the quasi-control of inquiry can only serve to estimate the adequacy of the various design modifications. Inference about these changes must be based on effects which the modifications are shown to produce in actual studies of subjects' behavior.

The non-experiment can be used in precisely the same manner. It has the advantage and disadvantage of eliminating cues from the drug experience. Here one would explain to a group of subjects drawn from the usual subject pool precisely what is to be done, show them the drug that is to be taken, give them the identical information provided to those individuals who actually take the drug, and, finally, ask them to perform on the tests to be used as if they had received the drug. This procedure has the advantage that the experimenter need no longer infer what the subject could have deduced about what was expected and how these perceptions could then have affected his performance. Instead of requiring the experimenter to interpret inquiry data and make many assumptions about how presumed attitudes and beliefs could manifest themselves on the particular behavioral indices used, the subject provides the experimenter with data in a form identical to that provided by those individuals who actually take the drug.

The fact that the non-experimental subject yields data in the form identical to that yielded by the actual experimental subject must not, however, seduce the investigator into believing that the data are in other ways equivalent. Inference from such a procedure about the actual demand characteristic components of the drug effect would need to be guarded indeed.

Such findings merely indicate that sufficient cues are present in the situation to allow a subject to know what is expected and these could, but need not, be responsible for the data. To illustrate with our example, if in doing the non-experiment one tells the subject he will be receiving three sleeping capsules and then asks him to do a test requiring prolonged concentration, the subject is very likely to realize that he ought to perform as though he were quite drowsy and yield a significantly subnormal performance. The fact that these subjects do behave like actual subjects receiving three sleeping capsules of sodium amytal would not negate the possible real drug effects which, in our example, are known to be powerful. The only thing it indicates is that the experimental procedure allows for an alternative explanation and needs to be refined. Again, the non-experiment would facilitate such refinement: if subjects instead of being told that they would receive sleeping capsules were told we are investigating a drug designed to increase

171 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

peripheral blood flow and were given a description of an experimental procedure congruent with such a drug study, they would not be likely to show a decrement in performance data. However, subjects who were run with the drug and such instructions would presumably yield the standard subnormal performance. In other words, the quasi-control of the non-experiment has allowed us to economically assess the possible effects of instructional sets rather than allowing drug inference. It is an efficient way of clarifying the adequacy of experimental procedures as a prelude to the definitive study.*

A somewhat more elaborate procedure would be to instruct subjects to simulate.† It would be relatively easy to use simulators in a fashion analogous to that suggested in hypnosis research. Two investigators would be employed, one who would administer the medication and one who would carry out all other aspects of the study. The simulators would, instead of receiving the drug, be shown the medication, would read exactly the information given to the drug subjects, but would be told they would not be given the drug. Instead, their task would be to deceive the other experimenter and to make him think they had actually received the drug. They would further be told the other experimenter was blind and would not know they were simulating; if he really caught on to their identity, he would disqualify them; therefore, they should not be afraid they would give themselves away since, as long as they were not disqualified, they were doing well. The subject would then be turned over to the other experimenter who would, in fact, be blind as to the true status of the subject. The simulating subject, under these circumstances, would get no more and no less information than the subject receiving the actual drug (except cues of subjective side effects from the drug). He would be treated by the experimenter in essentially the same fashion. This procedure avoids some of the possible difficulties of differential treatment inherent in the non-experiment. Even under these circumstances, however, if both groups produce, let's say, identical striking alterations of subjective experience, it would still be

* Obviously, extreme caution is needed in interpreting differences in performance of the individuals actually receiving the drug and that of the non-experimental control. The subjects in a non-experiment cannot really be given the identical cues and role support provided the subject who is actually taking the drug. While the identical instructions may be read to him, it is essentially impossible to treat such subjects in the same fashion. Obviously the investigator is not concerned about side effects, possible dangers, etc. A great many cues which contribute to the demand characteristics, including drug side effects, are thus different for the subject receiving the actual drug, and differences in performance could be due to many aspects of this differential treatment.

† The use of simulators as an alternative to placebo in psychopharmacological studies was suggested by Frederick J. Evans.

172 MARTIN T. ORNE

erroneous to conclude that there is no drug effect. Rather one would have to conclude that the experimental procedure is inadequate, that the experience of the subjects receiving the drug could (but need not) be due to placebo effects. Whether this is in fact the case cannot be established with this design. The only conclusion which can be drawn is that the experimental procedure is not adequate and needs to be modified. Presumably an appropriate modification of the demand characteristics would, if there is a real drug effect, eventually allow a clear difference to emerge between subjects who are receiving drugs and subjects who are simulating.

The interpretation of findings where the group of subjects receiving drugs performs differently from those who are simulating also requires caution. While such findings suggest that drug effect could not be due simply to the demand characteristics because it differs from the expectations of the simulators who are not exposed to the real treatment, the fact that the simulating group is a different treatment group must be kept in mind. Thus, some behavior may be due to the request to simulate. Greater evasiveness on the part of simulating subjects, for example, could most likely be ascribed to the act of simulation. Greater suspiciousness on the part of a simulator could equally be a function of the peculiar situation into which the subject is placed. These observations underline the fact that the simulator, who is a quasi-control, is effective primarily in clarifying the adequacy of the research procedure. The characteristic of this treatment group is that it requires the subjects actively to participate in the experiment in contrast to the usual control group which receives the identical treatment omitting only the drug, as would be the case when placebos are used properly.

The problem of inference from data obtained through the use of quasi-controls is seen relatively easily when one attempts to evaluate the contributions which demand characteristics might make to subjects' total behavior after receiving a drug. Clearly the placebo design properly used is the most adequate approach. This will tell us how much of the behavior of those individuals receiving the drug can be accounted for on the basis of their receiving a substance which is inert as to the specific effect but which mimics the side effects when the total experimental situation and treatment of the subject are identical. The placebo effect is the behavioral consequence which results from the demand characteristics which are (1) perceived and (2) responded to.* In other

173 DEMAND CHARACTERISTICS AND QUASI-CONTROLS

words, in any given context there are a large number of demand characteristics inherent in the situation and the subject responds only to those aspects of the demand characteristics which he perceives (there will be many cues which are not recognized by a particular subject) and, of those aspects of the demand characteristics which are perceived at some level by the subject, only some will have a behavioral consequence.

One might consider any given experiment as having demand characteristics which fall into two groups: (a) those which will be perceived and responded to and are, therefore, active in creating experimental effects (that is, they will operate differentially between groups) and (b) those which are present in the situation but either are not readily perceived by most subjects or, for one reason or another, do not lead to a behavioral response by most of the subjects. Quasi-control procedures tend to maximally elicit the subject's responses to demand characteristics. As a result, the behavior seen with quasi-control subjects may include responses to aspects of the demand characteristics which for the real subjects are essentially inert. All that possibly can be determined with quasi-controls is what could be salient demand characteristics in the situation; whether the subjects actually respond to those same demand characteristics cannot be confirmed. Placebo controls or other passive control groups such as those for whom demand characteristics are varied as independent variables are necessary to permit firmer inference.

IX. A FINAL EXAMPLE

The problem of inference from quasi-controls is illustrated in a study (Evans, 1966; Orne and Evans, 1966) carried out to investigate what happens if the hypnotist disappears after deep hypnosis has been induced. This question is by no means easy to examine. The hypnotist's disappearance must be managed in such a way as to seem plausible and truly accidental in order to avoid doing violence to the implicit agreement between subject and hypnotist that the latter is responsible for the welfare of the former during the course of the experiment. Such a situation was finally created in a study requiring two sessions with subjects previously trained to enter hypnosis readily. It was explained to them that in order to standardize the procedure all instructions, including the induction and termination of hypnosis, would be carried out by tape recording.

The experimenter's task was essentially that of a technician -- turning on the tape recorder, applying electrodes, presenting experimental materials, etc. He did not say anything throughout the study since every

174 MARTIN T. ORNE