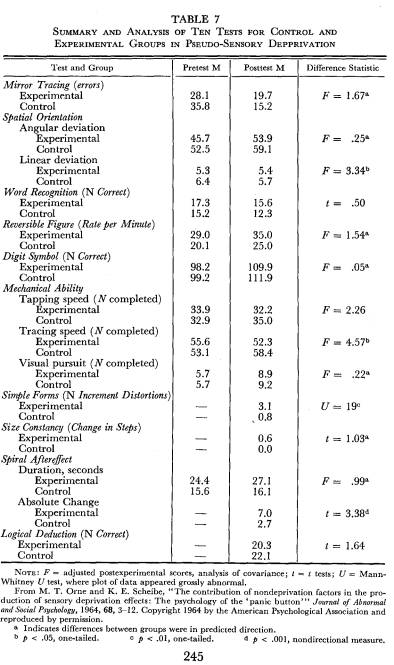

Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital and University of Pennsylvania

INTRODUCTION

It is the hope of understanding the sources of human behavior that has always been the basis of psychology. Regardless of whether attention momentarily turned to other species, to simpler mechanisms, or to apparently remote mathematical concerns, the ultimate object of interest has always been man. The very scientists who objectified psychology and examined simple processes of behavior in animals revealed an intense and abiding concern for improving the human condition. Pavlov, for example, devoted many years to the study of psychiatric treatment techniques; Watson invented the first behavior therapy for phobias; Hull helped found the Department of Behavioral Science at Yale which merged anthropology, psychiatry, and psychology; and Skinner wrote Walden II.

1. The research from our laboratory which is reported on in this paper was supported in part by Contract #DA-49-193-MD-2647 from the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command, Grant #AF-AFOSR-707-67 from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Contract #Nonr 4731(00) from the Office of Naval Research, and by a grant from the Institute for Experimental Psychiatry.

2. I would like to express appreciation to my colleagues, Harvey D. Cohen, Kenneth R. Graham, and David A. Paskewitz, for helpful comments in the preparation of this paper. I am particularly grateful to A. Gordon Hammer, Frederick J. Evans, Emily C. Orne, and David Rosenhan for their detailed criticisms and many incisive suggestions. Appreciation is also due Karen Ostergren for her editorial comments.

187

188 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

Some kinds of research can be carried out only with animals, but other questions which address themselves to human experience and complex human behavior can be asked only by studying human subjects. Not surprisingly, then, psychology's focus of interest has inevitably returned to man. In this discussion we will not be dealing with animal research. This paper will concern itself solely with experimental studies of human behavior and experience. Experimental studies of human behavior typically have considerable face validity. Generalizations from laboratory findings appear to have intuitive merit so that both the investigator and his scientific public are inclined to make the inferential leap to domains of behavior and experience beyond the laboratory. Such a leap is a complicated one, often not warranted on the basis of current evidence.

Consider the physical sciences. Assuming that conditions are kept constant, phenomena observed in the laboratory will tend to obtain outside the laboratory environs, but even here, under some circumstances, as Heisenberg has pointed out in atomic physics, the procedures involved in observing an event may so distort it as to make prediction impossible. This type of difficulty is a far more serious issue in psychology. Human behavior and experience may be distressingly modified when subjects are aware that they are being studied. The subject's participation in the psychological experiment may have significant motivational and perceptual consequences that can alter his behavior sufficiently to make inference to other contexts hazardous and, under some circumstances, misleading.

In most instances the purpose of carrying out an experimental study is the hope of answering significant questions about enduring human attributes, motivations, and behaviors. However, the psychological experiment is, by its very nature, what Garfinkel (1967) has called episodic. This means that it is regarded by everyone concerned as isolated from the rest of an individual's experience. It is implicitly understood that at the conclusion of the experiment the episode will be concluded and the individual will be basically unchanged. Fears expressed, actions undertaken, emotions felt in the context of an experiment are experienced as specific to that situation and intended not to carry over beyond it. In this regard it is analogous to other episodic events such as playing a game or having a good cry in response to a sad movie. Yet we hope to use observations obtained

189 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

in episodic situations to draw meaningful inferences about enduring motivations of individuals as they manifest themselves in nonepisodic contexts.

It is possible that some mental processes are more validly scrutinized in the laboratory than others. Sleep, for example, though perhaps modified somewhat by the situation, will, on the whole, be the same process within the laboratory as outside of it; but the tendency to rouse in response to stimuli is likely to be affected, and the content of dream reports even more so.

Hypnosis, with its potential for bringing about a meaningful dyadic relationship in a remarkably short time and permitting apparently profound modifications of a subject's experience, would appear particularly amenable to laboratory research. Here, hopefully, is a sufficiently robust phenomenon such that its effects ought to swamp any differences the experimental situation may introduce. Yet our experiences in studying hypnotic phenomena have served to focus attention on the peculiar nature of the psychological experiment. I do not think it is a mere coincidence that observations on the nature of the psychological experiment grew out of studies of hypnosis. Hypnosis is a caricature of a meaningful dyadic relationship and, as such, emphasizes and throws into relief components that, while present in a wide range of other situations, would not as easily be recognized elsewhere.

In this paper I intend to discuss some of our attempts to understand hypnosis and the implications of our studies for the understanding of the special nature of the experimental situation. I will, then, outline a number of procedures I have called quasi controls that are designed to help the investigator evaluate the potential impact of the experimental situation itself on the data that are obtained. I will also briefly illustrate the use of these methods in other areas of research. Moreover, I will try to discuss the particular problems and limitations of quasi controls and the difference between these and conventional controls (see Orne, 1969).

Once the implications of the subject's recognition that he is the object of study are recognized, it becomes tempting to explain away rather than to try to understand broad areas of research findings. It seems appropriate that hypnosis, which first uniquely demonstrated these problems, should also provide an unusually

190 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

compelling example of the limitations of the explanatory power of these ideas. For these reasons I have reviewed the evidence for and against the view that much of hypnosis can be understood by an exclusively motivational analysis. Thus, it has been widely accepted that the hypnotized subject has an increased motivation to please the hypnotist, a view that I myself formerly strongly supported (Orne, 1959b). This concept makes such sufficient intuitive sense that it had not been previously challenged, nor had it been tested empirically. When subjected to scrutiny, however, it becomes clear that it cannot account for the behavior of hypnotized individuals. Finally, I hope to outline constructive implications for psychological research that may be drawn from this work and the directions to which they point in future studies of human behavior and experience.

THE NATURE OF HYPNOSIS

Hypnosis is unquestionably a fascinating phenomenon, yet sooner or later most investigators become troubled by aspects of it that are not immediately apparent. With considerable distress they learn that their first-hand observations of hypnotic behavior seem not to be consistent with descriptions in the literature. Even more troubling, the more one reads the literature, the more confused the published picture becomes. It soon becomes evident that when the material is reviewed historically, very different behaviors have characterized hypnosis at different times.

Mesmer, for example, is considered the "father of modern hypnosis" (Binet & Féré, 1888; Boring, 1950), yet the behavior that occurred during his treatments does not at all resemble what is seen today. In his clinic, individuals would sit around an oaken tub filled with magnets, holding on to metal rods (to conduct the magnetic fluid). The surroundings were impressively carpeted and draped, music was played in the background, incense burned -- all designed to heighten expectation. Eventually, Mesmer, in magician's robes, would come down and, without uttering a word, lay his hands on one patient and then another. Patients would, one by one, appear to have a seizure, a hysteric fit, from which they went to sleep, only to awaken minutes or hours later without symptoms.

191 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

We do not see hysteric seizures followed by sleep as part of hypnosis today. Nor is hypnosis pursued nonverbally today. Rather today we speak to our patients and they respond peacefully, as it were, and without hysterics. Similar discordances between descriptions of behavior generally recognized to be hypnosis today and those of an earlier period can be found in the work of Coué (1922), not to mention Charcot (1886), who, for instance, indicates that if the top of the subject's head is rubbed he will pass from the stage of sleep to the stage of somnambulism.

It seemed to me important to determine how a phenomenon which everyone agrees is the same may be characterized by such variant behaviors. On the basis of White's (1941) theoretical framework, an experiment was developed to test the hypothesis that subjects in hypnosis behave in whatever manner they believe characteristic of hypnotized individuals (Orne, 1959b). For this purpose it was desirable to find an item of behavior that had not previously been associated with hypnosis and yet might seem plausible to the average college undergraduate. Such an item, by the way, was difficult to come by in view of the broad range of behaviors that, at one time or another, have been attributed to hypnosis. After some search, however, I came up with catalepsy of the dominant hand.3 While catalepsy itself is believed by some authorities to be an invariant accompaniment of hypnosis, when it occurs it always occurs in the entire body -- both hands, both feet, even the trunk. It had never been reported to occur in one hand while the other remained flaccid. Nevertheless, catalepsy of the dominant hand might sound plausibly scientific to an undergraduate psychology student, vaguely reminding him of learning about crossed hemispheres, stuttering, etc.

Two matched sections of a large college class were given a lecture on the nature of hypnosis which included a demonstration. Three "volunteers" were selected from the class and hypnotized. (Unbeknownst to the group, these individuals had been previously hypnotized and given a posthypnotic suggestion that the next time they entered hypnosis they would manifest catalepsy of the dominant hand.) Hypnosis was induced with the volunteers, and the

192 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

classic hypnotic phenomena were then demonstrated. Casually catalepsy was tested and, in passing, it was mentioned that catalepsy of the dominant hand was a typical hypnotic behavior. Two of the subjects happened to be right-handed and one left-handed, illustrating the point. In all other respects the lecture was accurate and the subjects were actually deeply hypnotized. The parallel class received the identical lecture and demonstration with the same three subjects. The only difference was that catalepsy was not tested and not commented upon.

Approximately one month later subjects from both classes were invited to come to the laboratory to participate in an experiment. When they were hypnotized we observed a new characteristic of the hypnotic trance -- catalepsy of the dominant hand -- associated exclusively, of course, with attending the appropriate lecture!

This experiment, trivial from one point of view, has, nevertheless, broad implications. It would appear that in hypnosis we are dealing with a chameleon. In other words, the subject's hypnotic behavior is influenced by whatever behaviors he believes to be characteristic of being hypnotized.

Today there seems to be considerable consistency in hypnotic behavior. I once asked a large number of individuals at random to describe hypnosis, and found that, despite initial disclaimers to the contrary, they invariably were able to describe the behaviors displayed by hypnotized people. The general views about the phenomenon can apparently be traced back to the descriptions given by Thomas Mann (1931) in Mario and the Magician and by George Du Maurier (1895) in Trilby. Although, of course, not everyone has read these two particular works, an incredibly large number of fictionalized accounts take their inspiration from them. We have been unable to find adults in our culture who do not have at least a rudimentary acquaintance with the kind of behavior which characterizes hypnosis.

The subject's prior knowledge about hypnosis is, of course, only one part of his knowledge of what constitutes appropriate behavior. Cues from the hypnotist, on an ongoing basis, also serve to define how a subject should behave. For this reason it is almost impossible to determine what precisely constitute the core phenomena of hypnosis. Working with children did not avoid the problem.

193 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

since even some six-year-olds appeared to have a reasonably accurate concept of what constitutes hypnotic behavior.

It seemed another way around this problem would be to ask anthropologists to work with a native population. One might reasonably assume that African Bushmen would not have read the slick magazines or been influenced by movies or television. These individuals would be truly naive. It sounded encouraging when a former student described hypnotized Bushmen as behaving very similarly to college undergraduates he had seen in hypnosis. The encouragement was short-lived, however, when it became clear what had occurred. The hypnotist, working through an interpreter, had proceeded to induce hypnosis. How was he to know, however, whether an individual was hypnotized? In order to recognize the state and report on it in some detail, he had very carefully, but without awareness, shaped the behavior until it resembled that with which he was familiar. This behavior pattern rapidly then became stable and reliably associated with hypnosis. In other words, while natives had not heard of hypnosis, the hypnotist had, and he then induced the kind of behavior with which he was familiar. Of course these observations can tell little about what the intrinsic behavioral characteristics of hypnosis are.

It should be noted that the hypnotist was proceeding in a rigorously empirical fashion to study hypnosis by hypnotizing naive subjects and observing their responses. He was able to note the differences in their behavior in hypnosis and outside of hypnosis. Unfortunately, the observed behavior was a function more of his preconceptions than of hypnosis. For example, had the hypnotist believed that catalepsy was an invariant accompaniment of hypnosis (a view, in fact, currently held by several outstanding clinicians), he would have been able to report that, in his experience, this is true not only with American subjects but even with naive natives. Thus we seem to be dealing with a phenomenon whose behavioral manifestations include whatever the hypnotist or the subject believes them to be. Two hypnotists with differing views can go out into the real world and validate their views by careful experiments without necessarily being aware that the behavior of their subjects mirrors their own preconceptions. It is not surprising, then, that the literature of this field has been characterized by an inability to

194 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

replicate and acrimonious disputes about the inaccuracies of other people's research.

Demand Characteristics in Hypnotic Research

When I became aware of the extent to which subjects' expectations and subtle cues from the hypnotist may affect the behavior of the hypnotized individual, there seemed to be no reason to assume that this would hold only for the general behavior which characterizes hypnosis; it should also affect those specific behaviors that are considered data in an experimental context using hypnosis. Subjects should respond not only to specific verbal suggestions but also to the context in which these suggestions are made. The behavior that is expected and desired of them in an experiment would, of course, be communicated only partially by the specific suggestions; it would also be communicated by subtle cues which the subject might have gathered about the experiment beforehand, cues given by the experimenter in the course of the study, and, perhaps most importantly, by the experimental procedure itself. The sum total of these cues which would communicate the purpose of the research, the hypothesis that the investigator hoped to demonstrate, the kind of behavior he expected to find, I termed the demand characteristics of the experimental situation.

I was first impressed with the effect of such variables while carrying out pilot work to elucidate the nature of hypnotic age regression. Controversy has long existed about the extent to which hypermnesia can reliably be induced by age regression. In previous work I had observed that in addition to increased memory one also finds increased confabulation (Orne, 1951). This observation had earlier been made by Stalnaker and Riddle (1932). It seemed reasonable to use the well-known Carmichael, Hogan, and Walter (1932) effect in serial recall as a means of studying this process. In their classic study it had been shown that labeling ambiguous figures would, with serial recall, yield a progressive change in reproductions in accordance with the labels. Thus the subject would be shown the original labeled ambiguous figures and then asked to draw six serial reproductions of these figures; he would then be age-regressed back to the time when he observed the original picture, and told to copy his hallucination. This should establish a

195 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

clear mnemonic drift in the direction of the label and away from the original figure. It would then be possible to discover whether age regression led to increased accuracy of recall or, instead, to increased confabulation.

The seven drawings could be randomized and then given to "blind" judges with the instruction to order them in the sequence in which they were made. Accuracy of recall would cause judges to place the seventh picture (the copy of the hallucination) early in the series, whereas an absence of increased memory or an increase in confabulation would leave the picture in seventh place, perhaps even cause judges to ask if some drawings were missing.

One subject showed the Carmichael, Hogan, and Walter effect to a striking degree. Thus when he reproduced an ambiguous picture that had been labeled "canoe," he was not satisfied to add pointed canoelike tips, but by the second time had added a paddle, and by the third and fourth drawings he had managed to fill in someone sitting and paddling, with his girl friend sitting in the bow, eventually adding a guitar, picnic basket, and other things which seemed to belong to the scene. Somehow the effect was working too well, and on a hunch the subject was told, "That's fine but now I want you to draw the design as you originally saw it." Very agreeably he accurately reproduced the original picture. When asked why he had elaborated the drawings so dramatically he explained that if the label said canoe, this would clearly be what was wanted, and if he was asked to reproduce it several times at half-hour intervals, naturally he would be expected to improve the resemblance to a canoe. Why else would he be asked to do this?

The subject's observation was extremely instructive. Incidentally, I have been unable to replicate the Carmichael, Hogan, Walter study despite several efforts to do so, and wonder about the extent to which similar factors may have determined the original results.

Subsequently, becoming more interested in this kind of effect, I replicated the Ashley, Harper, and Runyon (1951) study which had been planned to reconcile a controversy about the effect of economic status in children on perceiving coin size. At the time there was considerable controversy about the Bruner-Goodman effect (1947), which was that poor children perceive coins as larger than do rich children. This effect, while repeatedly replicated in

196 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

some laboratories, could not be found by others. Ashley, Harper, and Runyon had argued that the difficulty in showing a clear effect was the interindividual variability and what ideally would be desirable were perfectly matched subjects who differed only in the extent to which they perceived themselves to be rich or poor. Further, they argued, this could readily be obtained by hypnosis. Thus, the same subject could be tested in his normal state and in hypnotically induced rich and poor states. One would thereby have perfectly matched "groups" of subjects, differing only in the extent to which they believed themselves to be rich or poor. Using this technique, Ashley, Harper, and Runyon obtained data clearly supporting the Bruner-Goodman hypothesis.

A pilot study for the replication was carried out with a few subjects (Orne, 1959b) and it was clear that Ashley, Harper, and Runyon described a powerful effect indeed. In brief, the experimental procedure was to hypnotize the subject and obtain his coin size estimates, then to induce amnesia for the individual's past life and to provide him with a different life history. With the "poor" suggestion he was told that he came from a large family, that life had been hard on him, that while he managed to get by, there was never quite enough to eat, and that he had had to work extremely hard from an early age contributing to the family; it was possible for him to go on in school only by obtaining complete scholarships, and even then he worked extra to try to send whatever money he could home, and so on. When these suggestions were given, the subject's whole behavior changed. He became extremely intense in his efforts, seeming to care a great deal about the procedure, and when asked to make estimates by matching the size of a light spot of variable diameter to that of particular coins he would grossly overestimate. Again amnesia was induced for this experience and a new life history was provided, indicating that the student had come from a very wealthy family, that he could remember in his childhood how the chauffeur would take him to school in the Rolls, that he had lived in a big house, that his friends had envied him, that he had gone to the best schools and belonged to the best clubs, that he was somewhat annoyed because his monthly allowance had been cut to $2,000, which was barely enough to squeeze by on, and so forth. With these instructions the subject behaved very differently,

197 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

slouching and leaning back in the chair, showing a certain amount of contempt for the situation, apparently not caring about what he was doing, while judging the size of the coins considerably more accurately, with perhaps a slight tendency to underestimate.

There was one additional procedure which had been carried out by Ashley, Harper, and Runyon, which was to give each subject a metal slug four times with statements that it was made of lead, silver, gold, and platinum, respectively, and then to ask for size estimates for those identically sized disks. Again a lawful change in estimates of the disk size was shown, particularly under the poor condition, depending upon the value of the presumed composition of the disc.

When subjects were awakened and memory was induced for the experience, they were asked what the experiment was about. Typically they said they didn't know, weren't sure, and so forth. When pressed, without having been given cues as to what was expected, they suddenly began to explain that they supposed that I expected money to mean more to them if they were poor than when they were rich and that, therefore, it ought to seem bigger in the poor condition, whereas a rich boy would most likely see it as smaller.

It should be emphasized that nothing which had been said, as such, would have communicated why the experiment was being done. The suggestion per se would not have helped. However, the procedure itself was a dead giveaway. From the point of view of the subjects, they were being asked to make coin size estimates three times, the only difference being suggestions concerning the extent to which they saw themselves as rich or poor. If this was not sufficient to get the idea across, there was the matter of being given identically sized disks and asked to make coin size estimates, after being informed that the disks were composed of different metals. Certainly if the experimenter went to the trouble of telling them what these disks were made of, he anticipated differences in their responses, and the only parameter that was available for such differences to occur was that of perceived size. Therefore, it was the procedure rather than anything which the subjects were told that communicated the experimenter's expectations.

One subject, however, had a different idea. He came to an alternative, plausible hypothesis, which was that the poor students

198 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

would work harder and be more accurate in their estimates, whereas rich students would not care and their estimates would therefore go all over the lot. When the data were subsequently examined, it turned out that the subjects who formulated the Bruner-Goodman hypothesis yielded data which fully supported this hypothesis. The only aberrant subject was the one with the different hypothesis, and in his case the estimates made while poor were more accurate and showed less variability than those he made while rich. These data indicated that it would be vital to take into account the subject's perception of what was expected -- what I called the demand characteristics of the experiment -- in order to understand his behavior.

In a more systematic way another group of subjects was run in the Ashley, Harper, and Runyon design and careful post-inquiries were carried out. These inquiries were judged by independent judges, and a high degree of association could again be demonstrated between the perceived hypothesis of the experiment and the subject's performance.

It should be emphasized that the effect which demand characteristics have on behavior in such a situation ought not to be conceptualized as voluntary compliance with what the subject believes is expected of him. While this may in some instances occur, the more typical situation is one in which the individual's experience is changed by the situation. Thus Mesmer's patients did not voluntarily choose to behave as if they had a hysteric seizure; rather such a seizure resulted from the pressures of the total situation. If an appropriate interview could have been carried out with Mesmer's patients, it is likely one would have elicited the information that a seizure of this kind characteristically "happens" in the course of treatment.

Unfortunately, it was not possible with a procedure of this kind to determine whether subjects were actually responding to the demand characteristics of the situation or whether they were responding in line with the original hypothesis and subsequently, by reflecting upon their responses, deducing what had been expected. Accordingly, I wanted to devise a technique to explore what subjects might be perceiving in the situation without, however, first giving them the opportunity of responding in hypnosis. It could

199 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

not then be argued that the subject's response was predicated on the subjective experience of being poor or rich.

It was crucial in running a comparison group of this kind that it be exposed to the identical set of cues provided for the hypnotic group, since I had observed that hypnotists characteristically treated hypnotized subjects differently from waking individuals. One way to try to solve this problem was to ask subjects to simulate. But the literature was very explicit in indicating that subjects are unable to simulate successfully, and when I first applied the procedure it became clear that this was true. Thus, when I asked a subject to simulate hypnosis he would begin somewhat reluctantly and, after a few minutes, look at me somewhat sheepishly, smile, and ask, "Am I doing all right?" He might then proceed to simulate a few more moments, only to interrupt again or in some other way clearly indicate his ambiguous status. It would have been obvious to any discerning layman that these subjects were not hypnotized.

On reflection, however, it became clear why this was the case. Subjects knew that I knew they were simulating. They were being asked to carry out an essentially impossible task, namely, to simulate hypnosis knowing full well that I was aware of their actual status. There was no way in which they could "win."

A relatively minor variation of this procedure altered the situation in significant ways. In it, one of my associates instructed the subject, who had repeatedly been unable to enter hypnosis despite wishing to do so, as follows: "Your task today will be somewhat different. You are going to try to fool Dr. Orne and make him think you are actually going into deep hypnosis. He knows that he will be working with highly hypnotizable individuals who are able to enter deep trance but that some subjects will try to simulate. He will not know which is which, however. I can't tell you how to do this task. Do the best you can based on whatever knowledge you have of hypnosis. However, if Dr. Orne catches on to the fact that you are simulating he will stop the experiment immediately. So don't think you have given yourself away, for as long as he continues with the experiment, you will have been successful in fooling him. This is a difficult task but we have found some intelligent subjects are able to do it successfully. Good luck!" Given this simple instruction, untrained, unhypnotizable individuals proved capable of

200 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

behaving in ways which were exceedingly difficult to distinguish from the behavior of deeply hypnotized subjects. Without special test procedures experienced hypnotists were unable to discriminate these individuals at better than chance levels.4

The simulating subjects provided a way of evaluating in behavioral terms the kind of demand characteristics implicit in the experimental situation. We now had a group of subjects who were maximally responsive to the demand characteristics. When the Ashley, Harper, Runyon experiment was repeated with highly hypnotizable and simulating subjects run blind, we observed identical results in both groups.

It should be emphasized that the failure to find differences between subjects in the Ashley, Harper, Runyon design who are deeply hypnotized and those who are simulating tells us absolutely nothing about the Bruner-Goodman effect. It merely indicates that a highly plausible alternative hypothesis exists to explain the Ashley, Harper, Runyon finding: namely, that the response is a

201 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

function of the demand characteristics of the situation rather than the direct effect of the hypnotic suggestion to be "poor" or "rich."

Compliance as an Inadequate Explanatory Mechanism

With the recognition that many findings about hypnosis can be explained by the subject's response to the demand characteristics of the situation, it is inevitable that attempts should be made to explain the entirety of the phenomenon on the basis of such mechanisms. In an early attempt to conceptualize hypnosis (Orne, 1959b) I built upon the formulations of Hull (1933), White (1941), and Sarbin (1950) and proposed that hypnosis is characterized by (1) a desire on the part of the subject to play the role of the hypnotized subject, (2) an increase in suggestibility which was translated as an increase in motivation to conform to the wishes of the hypnotist, and (3) a less well defined aspect which I regarded as the essence of hypnosis, in the context of which increased motivation to please and a tendency to play the role of the hypnotized subject could be seen as epiphenomena. In order to understand the essential characteristics of hypnosis it would, of course, be necessary to determine how much of the phenomenon could be explained in terms of role playing and an increased motivation of the subject to please the hypnotist.

The close similarity between an increased motivation of the subject to please the hypnotist and a conceptualization such as an increased responsivity to the demand characteristics of the situation is not accidental. I assumed that the increased motivation to please the hypnotist was an intrinsic attribute of hypnosis. Perhaps because the formulation intuitively seemed sound or because it was congruent with the Zeitgeist, it was not challenged despite the absence of empirical evaluation. Indeed, it was perhaps inevitable that others would conclude that, because simulating subjects could mimic much of the behavior of the hypnotized individual, one could explain away the actual phenomenon. Not only has there been a tendency to assume that all hypnotic phenomena can be understood in terms of demand characteristics, but also demand characteristic effects have erroneously been equated with compliance.

Relatively recently, influenced by the work of London and Fuhrer (1961) and Rosenhan and London (1963a), I have begun to

202 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

examine empirical evidence bearing on the hypothesis that hypnosis increases the subject's motivation to please the hypnotist. It seems appropriate to review this work in the context of this paper, partly because it deals directly with motivational issues, but even more so because it clearly demonstrates the danger of explaining away rather than understanding a phenomenon. Certainly it shows that an uncritical -- and, in my view, inappropriate -- use of the concept of demand characteristics cannot adequately account for a complex phenomenon such as hypnosis.

There are three ways in which the concept of motivation to please the hypnotist or to comply with his wishes has been used to account for hypnotic phenomena: first, by way of the view that an individual who has been hypnotized by an experimenter is then more motivated to follow his instructions than if he had not been hypnotized; second, by way of the view that the tendency for an individual to enter hypnosis in the laboratory is merely a specific example of the general tendency to comply with requests of the experimenter (in other words, those individuals who enter hypnosis during an induction procedure are the very ones who initially already had a greater motivation to please the experimenter than those who do not respond in this way) ; and, finally, by way of the view that posthypnotic phenomena do not represent a special class of events but can simply be understood in terms of the subject's continued intense wish to please the hypnotist.

The Effect of Inducing Hypnosis on the Subject's Wish to Please the Hypnotist

On the basic question of whether the induction of hypnosis increases the motivation of the subject to comply with the wishes of the hypnotist it is difficult to obtain clear-cut findings. The widely held conviction that this is true is based on casual observations that hypnotized subjects seem to do whatever is requested of them. For this reason I normally begin my lectures to students by asking one individual to remove his right shoe, another to take off' his necktie, still another to give me his wallet, and still another to exchange his coat with his neighbor. After obtaining compliance with a number of utterly ridiculous requests of this kind, I ask the students whether they have been hypnotized, and upon receiving a

203 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

negative answer, I am able to point out that if they had previously gone through an induction process and had been asked to carry out the identical actions, observers would have said, "See, this demonstrates how a hypnotized individual is controlled by the hypnotist." Obviously this kind of control was already inherent in the student-teacher relationship; however, because the full amount of control one person might exert over another is normally neither exercised nor measured, it appears that hypnosis causes a significant increment in compliance. In a variety of ways we have tried to find behaviors which subjects would not carry out in the context of an experimental situation. We have been unable to do so. Thus, it has not been possible to demonstrate a unique increment in control due to hypnosis. (It was in the context of this question that the experiments in serial addition which will be referred to later were carried out.)

It is possible to phrase the question concerning the hypnotic subject's endurance thus: Will an individual in hypnosis perform a difficult task longer than he will out of hypnosis? Several studies have shown increased performance during hypnosis if one does not specially motivate the waking state (see Hull, 1933). Here the question of appropriate controls is exceedingly complex. This problem was traditionally phrased in terms of whether it is possible for hypnosis to cause an individual to transcend his normal volitional capabilities. Several studies have shown that it is relatively easy with appropriate motivation for nonhypnotized subjects to exceed their previous hypnotic performance (Orne, 1954; Barber & Calverley, 1964; Levitt & Brady, 1964). There can be no doubt that under these conditions the kinds of instructions used during hypnosis are quite different from those used in the waking state or for a control group. Furthermore, if subjects think that the experimenter is attempting to demonstrate increased performance during hypnosis they may easily provide him with supporting data, not by increasing their hypnotic performance but by decreasing their waking performance (see, for example, Zamansky, Scharf, & Brightbill, 1964).

One ingenious solution, eliminating differences in instructions, has been used in the study by London and Fuhrer (1961). These workers used identical hypnotic procedures for very good and very poor hypnotic subjects, both groups having been convincingly told that their hypnotic performance was adequate for the purposes

204 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

of the experiment. With a variety of physical tasks the authors report the startling finding that unsusceptible subjects showed a significantly greater increment in performance in response to hypnotic instructions than good hypnotic subjects. Certainly these findings do not support the general belief that hypnosis increases the motivation of the hypnotized individual to carry out whatever kinds of tasks are suggested. Evans and Orne (1965) have replicated these studies and, while their data did not reach significance, they showed trends in the direction reported previously. In any case, the results, again, do not support the view that there is an increase in performance with hypnosis.

As a subsidiary question in this section we may also ask whether hypnosis, without any specific posthypnotic suggestions, has the effect of enhancing a subject's wish to please the hypnotist after the trance is terminated. This is of particular interest to clinicians, for it has often been said that the induction of hypnosis alters the relationship between doctor and patient in such a way that the patient becomes more prone to accept, uncritically, requests by the doctor and, in some ways, becomes more dependent upon him.

We have carried out a study which bears upon this question. It makes use of a postcard-sending procedure that has also been employed in other studies to be reported later in this paper. It is therefore first of all necessary to describe this experimental procedure. (This technique was tested and then utilized to study posthypnotic behavior by Esther Damaser [1964] in our laboratory.)

The Effect of Laboratory Instructions on Behavior over a Period of Weeks

A technique was needed which would measure the extent to which individuals would persist in carrying out requests without any further reinforcement beyond knowing that their behavior was of interest and importance to the research study, and without knowing or understanding how that behavior would be used. We decided upon a task which would yield data over as long a period as desired and which would not necessitate the subject's returning to the laboratory or being given any feedback whatsoever (Orne, 1963). Particularly well suited to these criteria is the request to mail one postcard each day to a post office box. The subject can be

205 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

given any desired number of cards and appropriate instructions. The receipt of the subject's card provides quantifiable, objective data about the effectiveness of instructions in inducing individuals to carry out a trivial but tedious daily task.

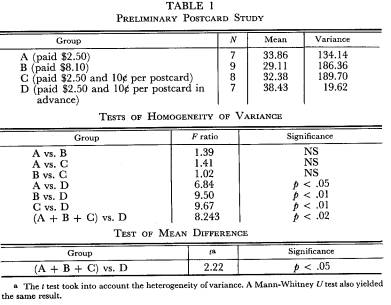

The first study, concerned mainly with evaluating the procedure, was designed to investigate whether or not a single experimental manipulation would visibly affect the rate of postcard sending, or whether individual variability was so great that the task would prove to be useless for experimental purposes. We postulated that the primary variable involved would be the manner in which the task was defined rather than monetary reward as such; in particular, that if subjects agreed to perform the task and were paid in advance for so doing, noncompliance would evoke guilt.

Thirty-four subjects solicited through student employment services were randomly assigned to four groups.5 All subjects were given a paper-and-pencil test and then one interview. During this interview they were told that another part of the experiment involved their doing something every day for eight weeks, that this something could be done at home and that it didn't take much time. The subjects were asked if they would like to participate in this part of the experiment. Three subjects refused, saying that they had enough to do without burdening themselves further; all the other subjects agreed to do this "something." Subjects were told that the reason for getting their commitment before explaining the task was that we did not wish them to discuss the experiment, and we felt it less likely that subjects who were actually taking part in the study would discuss it. After the subject had agreed to do this undefined something every day for eight weeks, he was given 56 preaddressed postcards and instructed to mail one every day.

Experimental groups differed as follows:

Group A. Subjects were paid $2.50 and were told that this sum represented payment for the entire experiment.

Group B. Subjects were paid $8.10 and were told that this sum represented payment for the entire experiment.

Group C. Subjects were paid $2.50 and were told that this sum was payment for participation in the paper-and-pencil test.

206 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

They were further told that they would be paid 10¢ for every postcard that they mailed, and that they would be paid this sum after the eight weeks had passed. They were told that they would be paid for only one postcard each day during the 56 days.

Group D. Subjects were paid $2.50 and told that this sum represented payment for participation in the paper-and pencil test. They were then also paid 10¢ per postcard and told that they were being paid in advance because we were confident that they would mail all of the postcards. Thus each of these subjects was given a total of $8.10, the same as Groups B and C, but of course the significance of this money differed for the three groups.

In analyzing the data, the number of postcards sent was corrected in such a fashion that subjects could get credit for only one postcard each day. As predicted, Group D performed differently from the other three groups in having a higher mean and a smaller variance (F = 8.243; .01 < p < .02). None of the other three groups differed significantly from each other either in their means or in their variances.

207 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

This finding, incidentally, confirmed our belief that subjects' motivation to undertake experimental tasks is not essentially a function of payment within the range of rewards usually given in laboratory research. However, the importance of the finding here is that it demonstrates that postcard sending over time is a behavioral task sensitive enough to be used as a measure of motivation.

The Effect of Hypnosis on Responses to Subsequent Requests

We are now prepared to return to the study (Orne, 1963) concerned with the effects of hypnotic trance on the subsequent relationship between the participants. It utilized 53 volunteer subjects for hypnotic research who were given 100 postcards with the request to mail one daily, much in the same fashion as previously described. If the successful induction of hypnosis does somehow make the experimenter more important to the subject, then the request to send postcards should be more effective with subjects who responded by going into hypnosis than with those subjects who failed to do so.

The 53 volunteer subjects were first administered an abbreviated version of the group adaptation (Shor & E. Orne, 1962) of the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale, Form A (Weitzenhoffer & Hilgard, 1959). Subsequently they were individually given a modification of a preliminary version of the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale, Form C (Weitzenhoffer & Hilgard, 1962), adapted to permit the administration of perceptual items and allowing an 11-point scale of hypnotic depth to be used. At the conclusion of the hypnotic part, subjects were asked by the same hypnotist-experimenter, in the same fashion as in the previous experiment, whether they would be willing to participate in something else. One subject did not agree to participate in the postcard tasks. All others were given 100 self-addressed postcards. The correlation was computed between postcard sending and hypnotizability.6 It was found to be -.11, obviously insignificant, and in a direction opposite to that required by the "compliance hypothesis." We feel compelled to conclude that the assumption of stronger compliance motivation on the part of successfully hypnotized subjects is not justified.

208 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

The Relationship between the Subject's Willingness to Please the Experimenter prior to Hypnosis and His Subsequent Response to Hypnotic Suggestions

Over the years we have worked with a large number of subjects. For methodological reasons we have been interested in the extremes of the distribution -- the highly susceptible and largely insusceptible individuals. One would expect that if good subjects are particularly motivated to please the experimenter they would be more reliable in keeping appointments and arriving punctually. Yet Emily Orne noticed in several studies which used insusceptible subjects and very good somnambulists that the insusceptible individuals were consistently more reliable and punctual. This was true despite the fact that everyone in the laboratory is exceedingly careful to treat subjects with consideration and to communicate our appreciation for their participation. This is particularly true with highly hypnotizable individuals, since they represent a relatively small proportion of the population and are essential for the research. (In studies which require subjects to come back more than once, the attrition rate of good somnambulists is especially striking.) For some time we have been studying arrival times in the laboratory. Evans and Emily Orne have been able to show consistent significant negative correlations between punctuality and the ability to respond to hypnosis. (These correlations also hold particularly well for later sessions.)

We have also done a pilot study with a small number of subjects (N = 17) evaluating the relationship between postcard sending and hypnotizability when the request is made before the question of hypnosis is raised with the subject. With a small sample of this kind no significant trends emerged. If there is a trend, it is unlikely to be of any significant magnitude. Neither of these results justifies the assumption that a stronger motivation to comply is characteristic of individuals who subsequently show that they are able to enter hypnosis.

The data most relevant to the relationship between effort and hypnotizability, where hypnotizability was measured afterward, were obtained by Rosenhan and London (1963a), investigating the baseline performance of subjects on physical endurance as measured by a hand dynamometer and weight holding, before the possibility that the subjects were to be hypnotized was mentioned. Significant

209 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

differences between susceptible and insusceptible subjects emerged, indicating a superior performance on the part of the insusceptible subjects. To the extent that we may assume no difference in physical capacity correlated with hypnotizability, these data suggest that subjects who prove to be good hypnotic subjects before the induction of hypnosis are, if anything, less motivated to follow the instructions of the experimenter than individuals who subsequently show themselves to be insusceptible. In a subsequent paper, the same authors (Rosenhan & London, 1963b) found an opposite trend in baseline responses related to the learning of nonsense material and suggest that baseline differences may be task specific. While further work is required on this issue, the indications are that those who become good somnambulists are not characterized by the general tendency to be highly motivated to carry out instructions.

Some data are available concerning baseline performances of subjects who know that hypnotic experiments will be conducted. Under these circumstances London and Fuhrer (1961) report that insusceptible subjects performed better on a variety of performance tasks. Shor (1959), during an experiment which required subjects to choose the highest level of electric shock that they would be able to tolerate, found good hypnotic subjects stopping at a considerably lower level of intensity than insusceptible subjects. Care must be taken in the interpretation of these kinds of data, however, as Zamansky, Scharf, and Brightbill (1964) have demonstrated that the relatively poor baseline performance of good hypnotic subjects may be a function of their wish at some level to have their hypnosis performance appear particularly dramatic.

POSTHYPNOTIC PHENOMENA

If one wishes to explain hypnosis as simply a function of the subject's wish to please the hypnotist, posthypnotic suggestion is of particular interest. It is the phenomenon which is usually associated with the notion of increased behavioral compliance on the part of the subject and, more than any other, implies an increased control over the individual's behavior. Yet here too, as we shall see, data do not support such an explanation.

Two studies were performed by Hull's group (1933) to measure

210 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

the persistence of posthypnotic behavior. Kellogg (1929) suggested to subjects that they would, while reading a book of sonnets, breathe twice as fast as usual on even-numbered pages and twice as slowly as usual on odd-numbered pages. Subjects were tested immediately after waking, on the following day, and then at intervals of one to two weeks and, in some cases, at longer intervals of up to 99 days. A control group of subjects was not hypnotized but given the same instructions. Kellogg's conclusions were as follows:

The performance of the waking control subjects shows no loss in the power of the suggestion with time. In all cases, at the last time of testing, nine or ten weeks after the instructions were given, the response is greater than at the first test. The performances of the trance subjects, on the other hand, show a loss in the force of suggestion with time, the ratio obtained at the last test being in all cases lower than at the first waking test. [p. 507]

Because Kellogg's experiment involved practice effects from repetition of the response, Patten (1930) investigated the persistence of posthypnotic suggestion over time, using each subject only once. They were instructed to press their right forefinger down when the names of animals appeared while they were looking for words which repeated themselves on the list revolving on a memory drum. Subjects were tested at time intervals varying from 0 to 33 days after the posthypnotic suggestion had been given. A waking control group was employed which was given the same instructions. The conclusions Patten draws are:

The magnitude of the response of the amnesic subjects decreases with time. The magnitude of the response of the conscious subjects decreases somewhat with time.... The reactions of the amnesic subjects are not as large nor as persistent as those of the conscious control subjects and they exhibit a somewhat faster decrement with time. [p. 325]

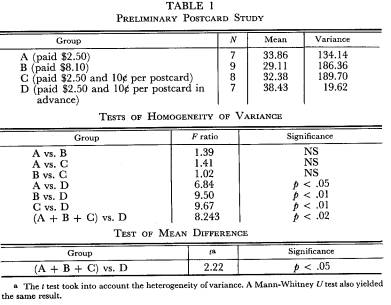

Damaser (1964) in our laboratory conducted a study of posthypnotic behavior utilizing the sending of postcards, which is a task rather well suited to an investigation of this phenomenon. It was felt important to control for possible personality and treatment differences between good and poor hypnotic subjects. For this reason a somewhat different design from that of the earlier study was used. From a large number of subjects, a group of very good hypnotic subjects and a group of subjects who were able to achieve only

211 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

medium hypnotic depth were selected. After the decision was made that a subject was adequate for the deep group, he was randomly assigned to one of three categories. The first group was given a posthypnotic suggestion in hypnosis that they would send one postcard each day, and they then were awakened with suggestions of amnesia. The second group was given the identical posthypnotic suggestion and then awakened with amnesia, but in the waking state was also requested to send one postcard each day. The third group was deeply hypnotized but not given any posthypnotic suggestion except amnesia; however, after being awakened each subject was asked to send a postcard every day. Thus of the three groups, one had "posthypnotic suggestion alone," the second had "posthypnotic suggestion plus a waking request," while the third had "waking request alone." These groups had been carefully equated for hypnotizability and had been exposed to the same amount of interaction, both hypnotic and waking, with the experimenter. The same design was carried through with the medium hypnotic group; here, however, the amnesia instructions for posthypnotic behavior were not given. The results are shown in Table 2.

212 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

Because of technical difficulties the sample sizes are too small to draw definitive conclusions. However, it will be noted that the deep and the medium "posthypnotic suggestion alone" groups sent considerably fewer cards than the other two groups. This finding is consistent with those reported by Kellogg (1929) and Patten (1930).

It must be pointed out that great care is needed in interpreting the observation that a simple request appears to elicit behavior from laboratory subjects more reliably over a longer period of time than a posthypnotic suggestion. From the point of view of the subject the task may be entirely different. Thus, the individual who has been given a posthypnotic suggestion tends to perceive his role in the experiment as complying as long as he feels compelled to do so; some subjects even interpret their role as trying to resist the suggestion. Characteristically, subjects do not feel it appropriate to push themselves to carry out suggestions, as they would perceive this to be cheating. This makes sense if the subject correctly appraises the purpose of the experiment as an attempt to measure the response to a posthypnotic suggestion. On the other hand, a subject complying with a waking request who has committed himself to the task views it as his obligation to carry it out as long as he possibly can. We should, therefore, not be surprised by the fact that the latter group of individuals carry out behaviors more consistently and over a longer period. It is for this reason that Damaser (1964) included the group which combined waking request and posthypnotic suggestion. We had hoped somehow to potentiate the waking request by means of posthypnotic suggestion. While results based on such small samples are presently equivocal, they do not point in that direction. If anything, posthypnotic suggestion interfered with the waking request, though the differences are not statistically significant.

Because of the different ways in which subjects interpret a waking request and posthypnotic suggestion, it is difficult to design an experiment with appropriate controls. Perhaps we need to be satisfied with recognizing that posthypnotic suggestion is a different phenomenon from the waking request. Certainly the consistently poorer performance of good hypnotic subjects should convince those of our colleagues who deny the existence of posthypnotic suggestion that what happens is at any rate different from simple compliance. And it should caution those of us who would assume

213 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

that hypnosis is a uniquely effective tool for the control of behavior.

However, from our present viewpoint another aspect of the data is perhaps more relevant. If we assume that hypnosis increases the motivation of the individual, certainly postcard sending in response to a waking request should be more frequent by good hypnotic subjects than by medium hypnotic subjects. However, if we examine our data on this, we find that the medium subjects sent considerably more postcards than the deep subjects a difference which would reach significance had it been predicted. Thus, here again we are compelled to dismiss the simple formulation that hypnotic phenomena are invariably associated with high motivation on the part of the good hypnotic subject.

Does the Subject Carry Out a Posthypnotic Suggestion in Response to Interpersonal Needs or to Intrapsychic Needs?

Two recent studies were designed to help clarify the mechanism of posthypnotic behavior and tend to show that the response cannot be explained in terms of pleasing the hypnotist. In one study by Nace and Orne (1970) it was reasoned that an overt response to a posthypnotic suggestion requires that the need to carry out the behavior be sufficiently strong to result in action; however, there may be forces opposing this action. If one considers those subjects who fail to respond to a posthypnotic suggestion, in at least some a strong residual action tendency must exist which is nearly sufficient to lead to overt behavior. In an appropriate situation, the effects of such an action tendency should be demonstrable.

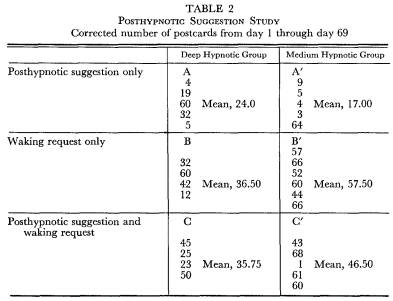

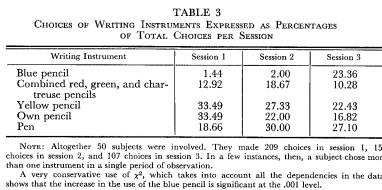

Subjects were seen in three experimental sessions in the laboratory. All the experimental rooms contained pencil boxes with a standard variety of different-colored pencils. On each occasion subjects were given one of the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scales (Weitzenhoffer & Hilgard, 1959, 1962) and were required to carry out other tasks, including filling out questionnaires and receipt forms for payment. The latter activities provided opportunities for unobtrusive observation of choice of writing instrument, four times in the first session, three in the second, and two in the third. In the third session, Form C of the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (Weitzenhoffer & Hilgard, 1962) was used, but to it the following

214 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

posthypnotic suggestion item was added: "When you wake up and I take off my glasses you will feel a compelling desire to play with the blue pencil." After the trance the posthypnotic suggestion was tested, and the subject's experiences during the session were discussed with him without any particular reference to the posthypnotic suggestion. The experimenter then indicated to the subject that before finishing, it was necessary for him to fill out another questionnaire, asked him to make himself comfortable behind the desk, and left the room. Later the secretary observed which writing instrument was chosen to sign the receipt. Thus, in the third session both opportunities for observation of choice of writing instrument came after the cue for the carrying out of the posthypnotic suggestion.

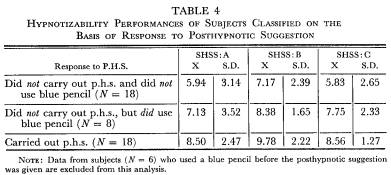

The question was whether subjects who had received the posthypnotic suggestion but had not carried it out would now tend to choose the blue pencil for filling out the questionnaire. The task required the subjects to use some writing implement, and therefore provided them an opportunity to discharge, in the absence of the hypnotist, an action tendency that had previously been insufficiently strong to be expressed in behavior. The results, set out in Tables 3 and 4, were strikingly lawful. The very best hypnotic subjects, of course, carried out the posthypnotic suggestion. The essentially unsusceptible individuals did not carry out the posthypnotic suggestion, nor did they tend especially to use the blue pencil in filling out the questionnaire. However, those individuals who responded to a good many of the hypnotic items but did not enter a very deep trance were the ones who subsequently used the blue pencil for the

215 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

questionnaire. These data strongly support the view that a posthypnotic suggestion which is not carried out will, in some subjects, nonetheless lead to an action tendency which, under appropriate circumstances, will manifest itself in overt behavior. The use of the blue pencil in filling out the questionnaire can be seen as a relatively easy posthypnotic test item. Of relevance to our discussion here is that the use of the blue pencil occurred not in the presence but in the absence of the experimenter, apparently serving an intrapsychic need, perhaps being analogous to a Zeigarnik effect (1927). It would seem that the posthypnotic suggestion certainly increased the likelihood of the use of the blue pencil, but that this effect was not the same thing as an increased tendency to please the hypnotist.

Using a very different approach, Orne, Sheehan, and Evans (1968) investigated the effect of a posthypnotic suggestion on behavior occurring outside the experimental context. Fisher (1954), in a now classic study, hypnotized subjects and gave them the posthypnotic suggestion that whenever they heard the word "psychology" they would scratch the right ear. On their awakening, he tested the suggestion and found they responded. Shortly thereafter one of his colleagues entered the room, and a "bull session" ensued, implicitly terminating the experiment. During this session the word "psychology" came up, and 9 of the 12 subjects failed to respond. When the colleague eventually left, Fisher turned to the subjects in such a way as to imply that the experiment was still in progress, and used the word "psychology" conspicuously, thereby eliciting the suggested ear scratching in all subjects. These findings have supported the view that posthypnotic behavior can best be

216 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

understood as the result of the subject's providing what the hypnotist desires of him. There are two issues subtly intertwined in this experiment, however: (1) whether the subject will carry out a posthypnotic suggestion outside the experimental context if he is not specifically required to do so, and (2) whether the subject's interpretation of an ambiguous suggestion can subsequently be modified by the hypnotist.

Consider the suggestion: "Whenever you hear the word ‘psychology’ you will scratch your right ear." It would seem extremely unlikely that the suggestion was intended or taken to mean that henceforth and for the rest of his life the subject was to respond by scratching his right ear whenever he heard the word. Rather, most subjects would correctly interpret it to mean "As long as this experiment continues, you will scratch your right ear whenever you hear the word ‘psychology.’" If subjects interpreted it in this fashion, their behavior was merely an appropriate reflection of how they perceived an ambiguous instruction, and would have no bearing upon the more basic issue of whether an unambiguous posthypnotic suggestion would be carried out outside an experimental setting.

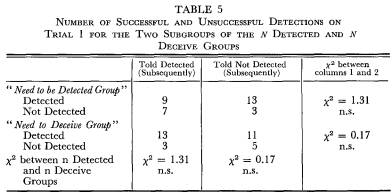

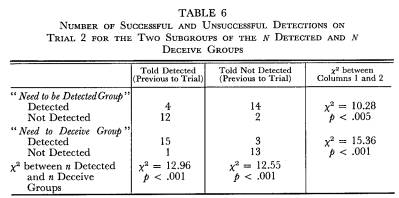

It is to this latter issue that the Orne, Sheehan, and Evans (1968) study was addressed. Subjects, whose hypnotizability had carefully been established in earlier sessions, were solicited for an experiment which involved two sessions on succeeding days. This requirement was discussed with them prior to their coming to the laboratory. On the first day they were given a series of personality tests and deep hypnosis was induced. At that time they were given the posthypnotic suggestion that for the next 48 hours whenever they heard the word "experiment" they would run their hand over their head. It should be noted that this suggestion has a specific time limit which is legitimized by the fact that the individual will be returning to the laboratory on the succeeding day. The session was completed, the subject sent home. The next day when he came to the laboratory and the investigator came to pick him up in the waiting room, as they walked down the corridor the latter remarked casually, "I appreciate your making today's ‘experiment.’" This, however, was not the crucial test. Subjects are reimbursed for their experimental participation in the main office, which is some distance

217 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

from the experimental suite, but through which they must pass in order to come and go. This is a routine procedure to which subjects had earlier become accustomed. As the secretary paid the subject on the first day, in a perfunctory fashion she asked him to sign the payment receipt for the "experiment." The next day when the subject arrived in the waiting room, he was met by the receptionist, who asked whether he was there for the psychological or the physiological "experiment." These, then, were the crucial tests outside the experimental context.

A crucial issue bearing on the interpretation of the findings was whether the secretary and receptionist were indeed perceived to be outside the experimental setting or whether the subject recognized them to be really agents of the experimenter. For these reasons, a special group of quasi controls simulating hypnosis was also run. The hypnotist was blind to the actual status of the subjects. By virtue of their instructions, simulating subjects (a comparison group which we will discuss at greater length later) are particularly prone to be suspicious of the experimental situation. As a result, they provided a very hard test of whether the hypnotic subjects perceived what happened in the main office and the waiting room as part of the experiment or not.

The results were clear. Deeply hypnotized subjects characteristically responded to the posthypnotic suggestion outside the experimental context, whereas simulators characteristically did not. The greater tendency to respond outside the experiment on the part of the deeply hypnotized subject was matched by an equally interesting difference within the experimental situation. Thus, simulators responded more consistently to the posthypnotic suggestion when the word "experiment" was used by the hypnotist than deeply hypnotized subjects, who occasionally seemed unaware of the use of the word when it was sufficiently well embedded in the context.

These findings indicate that the posthypnotic phenomenon cannot be explained by a strong motivation on the part of the hypnotized subject to please the hypnotist. Rather, the posthypnotic suggestion appears to set up a temporary compulsion for the subject to respond independently of whether the hypnotist is present or even aware of the response.

218 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

INCONSISTENT NONEXPERIMENTAL OBSERVATIONS

Throughout this discussion we have examined data selected because they raise questions about the assumption that hypnosis necessarily increases the motivation of subjects to carry out the request of the hypnotist. The most relevant area where one would find evidence to support this view is the clinical situation. It is the impression of all therapists with whom I have discussed the matter that the induction of hypnosis during treatment seems to intensify the transference relationship and thereby more rapidly makes the therapist a significant figure for the patient. Gill and Brenman (1959) have discussed this issue at length in their classic text.

Equally relevant are the clinical data on the removal of symptoms. These data, in fact, provide the only clear-cut situations where individuals can be shown to undertake behavior in response to a request in hypnosis, which they appear unwilling or unable to undertake on the basis of a waking request. Unfortunately, truly controlled data are lacking, and a study is needed to investigate in a rigorous fashion the extent to which the induction of hypnosis facilitates symptom removal. One observation has often been made, namely, that the success of therapeutic suggestions does not depend upon the depth of hypnosis (as traditionally measured) achieved by the patient. Thus, sometimes individuals who would, by a laboratory definition, be considered unsusceptible show a dramatic therapeutic response. This point is interesting in the light of London and Fuhrer's (1961) findings that hypnotic procedures affect the performance of individuals who appear unsusceptible to hypnosis as measured by standard tests.

Another type of evidence, best exemplified by Pattie's (1935) paper on uniocular blindness, shows that some subjects will go to incredible lengths to succeed in following a suggestion. Thus, one of his subjects spent hours in the library learning about optics in order to be able to maintain the appearance of uniocular blindness. Similarly, subjects will, in response to a suggested burn, produce localized scratch marks and will, if given the opportunity, often actually burn themselves surreptitiously with a cigarette, thus raising a blister. It would be possible to go on in this way indefinitely, listing anecdotal data which suggest the intensity with

219 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

which some subjects attempt to meet the demands placed upon them by a hypnotic suggestion. Indeed, it is this kind of evidence which causes us to assume so easily that an increase in motivation is a concomitant of hypnosis.

There are, however, differences between the clinical situation and the experimental one. In the former, suggestions are given that have intense personal reference, whereas in the latter the tasks are obviously peripheral to the interests of the subject. Further, most anecdotal evidence, such as that presented by Pattie, is based upon work with subjects with whom the experimenter has had prolonged and intense contact. These situations, though in a laboratory context, approximate clinical situations. Perhaps it will be necessary to distinguish between what happens as the result of largely impersonal induction of hypnosis in the laboratory and the phenomenon we see in clinical practice based on a highly meaningful, intensely personal relationship. In the laboratory little or no contact with the experimenter is necessary for the induction of hypnosis. Even a tape recording is fully adequate as an induction stimulus. Hypnosis takes place largely as a function of factors (such as attitude, aptitude, personality, etc.) which the subject brings to the experiment. This is, of course, quite distinct from the situation in clinical practice, where there usually exists a significant personal relationship, as well as the patient's expectations of help. It is quite possible that there is an interaction between the induction of the hypnotic phenomenon, its effect on the motivation of the individual, and these two types of settings.

To recapitulate briefly, the main points that have been made so far are:

1. Using human beings as subjects in the context of episodic relationships (in hypnotic studies and other psychological experiments) is a complex matter. Generalizing from episodic laboratory behavior to everyday life is hazardous.

2. This became particularly apparent in our early studies on hypnosis which indicated (a) that the very heterogeneous behavioral events associated with hypnosis may all be viewed as behaviors that meet "the expectations of the hypnotist," and (b) that the effects of demand characteristics can determine the

220 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

kinds of data that are obtained in studying mental processes, where hypnosis is used as a means to induce those processes.

3. The whole question of the interaction of the motives of experimental subjects with their changing perceptions of the total experimental context needs to be scrutinized.

4. This kind of examination of the hypnotic situation reveals that the phenomena cannot, in fact, be fully explained in terms of strong or increased motivation to comply with the demands of the hypnotist, though, no doubt, some compliance occurs in the course of interpersonal relations such as therapy or in experimental situations where compliance is inevitably maximized.

We shall now turn to a closer look at the operation of demand characteristics in experimental situations other than hypnosis.

THE EXPERIMENTAL SITUATION AS A SPECIAL FORM OF INTERACTION

Our model for experiments comes from the physical sciences. There, in order to establish the effect of a particular independent variable, one compares objects exposed to a particular value of the variable with control objects which are not, all other conditions being held constant. When the object of study becomes an active, sentient human being, his awareness of the process of study may interact with the parameters under study. This is obvious in hypnotic research, but the problem is present in varying degrees in all behavioral research involving man.

THE MOTIVATION OF THE EXPERIMENTAL SUBJECT

Far from being passive responders, as assumed by the conceptual model of the traditional experiment, subjects are active participants in a very special form of social psychological interaction which we call the psychological experiment. A subject does not miraculously arrive in the experimenter's laboratory, but he is brought there by specific incentives. He is somehow solicited. Even if participation is made obligatory in the context of a course, a modicum of cooperation must in some way be involved, and more often than not we are

221 Hypnosis, Motivation, and Ecological Validity

dealing with individuals who have had the option of participating and have volunteered. While we tend to use financial rewards to secure subject participation in our research, the level of monetary reward usually involved is hardly sufficient to compensate the individual for his time, much less for the tedium, discomfort, or even pain that may be involved. With the exception of the occasional "professional subject," payment (within the range of monetary reward usually employed) appears secondary.

Elsewhere (Orne 1959a, 1962, 1970), I have emphasized that a great many subjects volunteer to participate in research in the hope of helping science, contributing to human welfare, and so forth. Certainly there is also a wide range of other motives that bring the subject to the laboratory. These include not only curiosity and an interest in learning about experiments but also, not infrequently, hopes of obtaining some form of personal help by participating. Whatever brings the subject, it is my conviction that he soon acquires a stake in the research. Seeing that he is already there and already participating, he is likely to want his participation to be useful. While no doubt subjects are concerned about what psychologists think of them and how they evaluate them -- a motive that has been singled out, emphasized recently by Milton Rosenberg (1969), and termed "evaluation apprehension" -- I have been equally impressed by the extent of the subject's concern to have his data be useful to the investigator. For example, in a psychophysiological study, equipment failure can in no way be construed as reflecting upon the subject's capabilities, yet it is invariably resented. In one way or another subjects tend to experience great concern about the success of the study as a whole and hope that their performances will contribute to it.

In the context of research subjects are willing to tolerate discomfort and even pain, so long as it seems relevant and necessary to the research task at hand. However, this tolerance is limited to discomfort that is perceived as essential for the research. For example, subjects will accept with relatively little annoyance repeated venipunctures in order to permit the investigator to draw several blood samples at different times in the course of an investigation. However, they greatly resent being stuck twice in an experiment requiring a single venipuncture because the investigator is unable

222 Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1970

to find the vein the first time. Whereas in the former case the discomfort associated with blood samples being taken was necessary for the purpose of the experiment, in the latter instance the additional discomfort of the second puncture is related to the experimenter's ineptitude rather than the needs of the research.