The Institute of Pennsylvania Hospital and University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19139

The well-documented fact that it is possible to carry out major surgery with hypnosis as the sole anesthetic demonstrates that hypnosis can, in suitable individuals, effectively suppress pain. Patients have tolerated procedures ranging from thyroidectomies to cesarian sections, from bone marrow aspirations to open heart surgery, with hypnosis as the sole anesthetic. There is evidence that reflex responses to pain are maintained, and varying degrees of flinching may also occur. Nonetheless, if the patient is asked whether he is comfortable at these times during the operation, he will insist that he feels no discomfort. Following surgery, he will continue to maintain that he was relaxed and felt no pain throughout the experience.

We lack a fully satisfactory theory to account for this phenomenon. Certainly, the mechanism of action is not analogous to local anesthesia. On the other hand, the anesthetic response is specific to the part of the body where anesthesia had been suggested. For example, during abdominal surgery with hypnoanesthesia, the patient may well complain about an unexpected pinprick on his arm. Thus, the process is in no way analogous to general anesthesia of any kind, not to speak of the fact that the patient remains in communication with the hypnotist throughout the procedure. Again, regional or spinal anesthesias are not comparable in that they follow clear-cut neurological patterns, which is not the case with hypnotically induced anesthesia.

It is not surprising, therefore, that controversy persists to the present day. Since the time of Mesmer, some have tried to explain away this puzzling phenomenon by arguing that the responsive individual is merely voluntarily suppressing his extreme discomfort. Conceivably, one might argue that the patient, having gotten himself into the situation, somehow controls himself. Yet, it is hard to understand why a patient should choose to suffer when he knows that relief is immediately available to him if he but asks for it. Even if one were to accept the implausible notion that patients merely choose to suffer to please the hypnotist, it becomes totally inexplicable why a patient who had been operated on once under hypnosis would seek out this form of anesthesia a second time knowing full well that safe and effective chemical anesthetics are ready alternatives.

It is clear that if we accept Dr. Sternbach's (7) apt definition of pain as a personal, private sensation of hurt, that hurt is not consciously experienced.

847

848 HYPNOTIC METHODS FOR MANAGING PAIN

The fact that some reflex responses to pain stimuli are clearly evident and some involuntary flinching can occur in no way alters the absence of hurt. By the same token, however, we should be aware that the explanation for suggested anesthesia must probably be sought in the profound effect hypnosis may exert on selective attention. The well-known phenomenon of an athlete suffering a normally very painful trauma of which he is unaware until the athletic contest is completed clearly shows the capacity of some individuals at least to suppress an awareness of pain. Why hypnosis is capable of mobilizing these abilities, which otherwise come to the fore only in life-and-death situations or at least in contexts of extreme commitment and motivation, are matters that remain to be understood.

We are not concerned here with the use of hypnosis as the sole anesthetic. There are few indications for such a procedure, although the fact that it is possible helps to underline what the hypnotized individual is capable of doing. We seek to distinguish among the use of hypnosis in (a) the treatment of acute pain, (b) the treatment of persistent pain with a clear-cut physiological basis as opposed to the treatment of what is generally considered, and (c) chronic pain, involving longstanding pain with an ambiguous etiology.

USE OF HYPNOSIS IN THE TREATMENT OF ACUTE PAIN

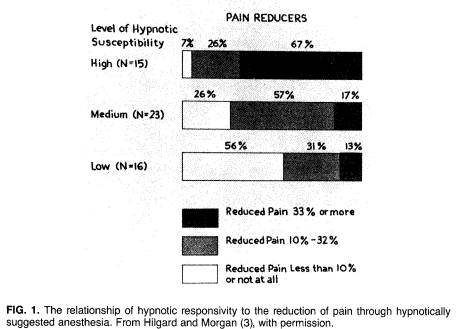

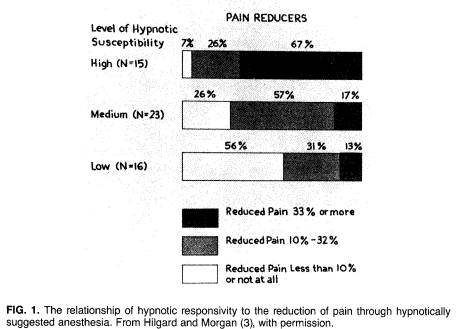

Individuals differ in their abilities to respond to hypnosis. There are now reliable techniques available to assess the subject's response, and there is a high relationship between the subject's response to hypnotic items other than anesthesia and his ability to develop analgesia. As Hilgard and Morgan (3) show, of those individuals who were highly responsive to hypnosis, 67% were able to reduce experimental pain more than 33%, and all but one of the 15 subjects reduced pain more than 10% (Fig. 1). On the other hand, of those individuals who showed little hypnotizability, half were unable to reduce pain by even 10%.

In contrast to these observations, which were obtained in the laboratory, it is the experience of a great many dentists who work with hypnosis that well over 90% respond to hypnosis, becoming relaxed, more comfortable, and able to tolerate pain. This paradox can be understood once it is recognized that hypnosis may exert a specific effect in the sense of a negative hallucination of pain which requires considerable hypnotic skill. It is hardly surprising that the ability to ignore the experience of pain is related to the individual's ability to ignore a visual perception or to block out sounds other than the hypnotist's voice. On the other hand, if an individual expects hypnosis to be helpful to him, and he is subjected to a hypnotic induction procedure that causes him to relax profoundly, a placebo effect can be observed.

In other research, McGlashan et al. (5) have shown that there is no correlation between hypnotizability and the response to placebo overall. Further, for unhypnotizable subjects, the correlation between the response to placebo and

849 HYPNOTIC METHODS FOR MANAGING PAIN

the response to hypnosis is 0.76, suggesting that for people who cannot respond to hypnosis, the inert medication provides the same level of relief as what is for them the inert hypnotic procedure. That is, they have significant relief, but it is not related to hypnotizability. On the other hand, for highly hypnotizable subjects, there is no correlation between the response to placebo and the response to hypnosis. Further, the response to hypnosis is of an entirely different order of magnitude than the response to placebo, whereas the hypnotizable individual's response to placebo is of the same order of magnitude as the unhypnotizable individual's response.

One further point is relevant. Evans (1), in a reanalysis of these data, noted that those subjects with high state anxiety were the ones who benefited from placebo; those who were not anxious did not benefit from placebo. These observations would seem to explain why in a dental context, where most patients who are offered hypnosis have a high level of state anxiety, this procedure provides some relief in virtually everyone. Even those individuals who are unhypnotizable will nonetheless show a marked reduction in pain as the placebo response to the hypnotic induction. Obviously, those who have some hypnotic ability will also additively have a specific response to the analgesia suggestion.

It should be emphasized, however, that the level of anesthesia that is generally wanted in the dental setting means that the patient is able to hold still for an injection of lidocaine, an important accomplishment given a patient with dental phobia but one that involves more the control of anxiety than the

850 HYPNOTIC METHODS FOR MANAGING PAIN

control of pain. With some dental patients, however, it is possible to do a wide range of dental procedures that involve high levels of pain with no anesthetic other than hypnosis. These individuals are likely to be the ones who are hypnotizable and who are capable of responding to suggestions of anesthesia.

The two independent mechanisms are emphasized here; otherwise, many clinical descriptions simply do not make sense, and the practitioner wishing to use hypnosis is likely to be disappointed. On the other hand, recognizing that even unhypnotizable subjects are capable of gaining some measure of relief allows the clinician to utilize the anxiety reduction associated with profound relaxation in those individuals who are incapable of responding to hypnosis and to utilize the patient's hypnotic skill when it is present.

Although surgical anesthesia by means of hypnosis is justified in only the rare cases where there is a contraindication to chemical anesthesia, hypnosis can be used routinely as a preoperative procedure to reduce the amount of medication required. It has been shown repeatedly that simply lowering anxiety reduces the amount of amobarbital needed to produce surgical anesthesia. Indeed, this effect is so reliable that the amount of amobarbital required until the patient reaches his sedation threshold as indexed by dysarthria has been used as a measure of anxiety (6). The amount of time required for hypnosis is quite limited and can be adapted to fit with the usual preoperative procedures used for anesthesia, recognizing, of course, that the goal is merely to reduce the need for the amount of medication employed preoperatively and during surgery, not to provide anesthesia. Since this primarily involves anxiety reduction, it is effective with well over 90% of the patient population.

To summarize the control of acute pain by hypnosis, we can state that it is a safe procedure, but its limitations are primarily the inherent ability of the individual to respond to hypnosis. Only some 10% of the population can achieve a sufficient degree of hypnotic anesthesia so that major surgery can be performed. Others may obtain varying degrees of relief. However, the anxiety reduction aspect of relaxation is applicable to all patients.

TREATMENT OF PERSISTENT PAIN -- CHRONIC PAIN SYNDROME

It is important here to distinguish between what has come to be referred to as chronic pain problems, where the etiology is generally ambiguous but, whatever the etiology, there are major functional factors complicating the picture, and persistent pain of clear organic etiology.

Let us consider the chronic pain syndrome first. One of the major advances in the treatment of pain is in the recognition that the symptom may serve needs largely unrelated to the experience of pain. These are the pain patients who present the most trying management problems for the practitioner. Usually the pain syndrome starts following a relatively minor injury and persists. The patients are willing to undergo almost any kind of treatment to

851 HYPNOTIC METHODS FOR MANAGING PAIN

obtain relief, but somehow nothing seems to work, and the clinician often has an uncomfortable feeling that the patient is somehow sabotaging therapy despite his superficial cooperativeness. Since there is some vague organic pathology, one cannot be certain about the functional origin of the pain, and yet careful evaluation makes it clear that pain behavior serves an important role in stabilizing the patient's environment and helping him obtain some degree of attention and interest from those around him. It is well to remember that for some individuals even being the object of anger is often preferable to being ignored.

In some instances, the symptom of pain turns out to be a depressive equivalent, something to which one should be alerted if the patient gives a history of sleep disorder, fatigue, lack of interest -- sexual or otherwise -- an inability to work, or a tendency to stay in bed, especially with a history of previously effective functioning. These are, of course, the individuals who respond dramatically to tricyclics and other antidepressant therapy.

In many individuals with chronic pain syndromes, the most appropriate treatment depends on behavioral management so that the contingencies associated with manifesting the pain response are no longer desirable. As long as the pain response is rewarded, either by a pension, which from the patient's point of view is greater than he will be able to earn on his own, or by attention and caring, which he feels he cannot obtain in other ways, the likelihood of relieving the chronic pain syndrome is slim indeed.

We do not intend to discuss these matters in great detail except to emphasize that hypnosis is not the appropriate treatment for functional pain. I want to emphasize this because it seems so sensible to consider treating a psychological problem by psychological means, and certainly hypnosis is a psychological treatment. However, hypnosis is not an effective means of causing an individual to modify behavior he is not willing to modify. It is an effective technique to modify an individual's experience. Consequently, it is possible to block the appreciation of pain, but when one is dealing with a syndrome in which a major factor involves the consequence of pain behavior -- in other words, where the patient is rewarded for demonstrating his suffering - hypnosis is not likely to provide more than very transient relief.1

Thus far, we have discussed only the use of hypnosis to suppress the experience of pain by direct or indirect suggestion. Although behavior therapy for pain is one of the most promising approaches, some psychotherapeutic interventions have been effective, especially in those instances in which the patient has become increasingly uncomfortable with the situation and his use of pain behavior as a technique of adjustment does not appear to be fully effective. In the context of an overall psychotherapeutic setting, hypnosis may be useful in helping to uncover conflict situations the individual has been

852 HYPNOTIC METHODS FOR MANAGING PAIN

unable to discuss previously, but it is important that the therapist refrain from slipping in suggestions directed at the symptom. The treatment of chronic pain by direct suggestion is usually unsuccessful, but in some instances in which it has been successful, it has led to serious symptom substitution, the most typical result being acute depression. Of course, since we now recognize that a masked depression may be responsible for the pain symptom, it should not be surprising that a suppression of the pain symptom may result in a fullblown depression. Yet it is interesting to note that this complication is rarely if ever seen by the behavior therapist, raising the possibility that hypnosis may act in a quite different manner, at least in some instances.

In sum, then, hypnosis is not the treatment of choice for functional pain. Chronic pain syndrome should best be treated by behavioral techniques or, if it appears to be a masked depression, by appropriate antidepressants. Finally, some chronic pain syndromes may be treated psychotherapeutically, and in those instances, hypnosis can play a role in facilitating uncovering techniques, but the therapist should avoid the temptation to give direct suggestions for the relief of pain.

TREATMENT OF PERSISTENT PAIN OF CLEAR PHYSICAL ETIOLOGY

The area in which hypnosis has been most appropriately used as a technique to control pain involves pain syndromes with specific organic etiologies: shingles, the crises of sickle cell anemia, the need to change burn dressings over long periods of time, repeated bone marrow aspirations, particularly with children, and, of course, pain associated with terminal cancer. These are the groups of patients who present some of the greatest challenges to the physician, and hypnosis is one of the few effective ways of providing relief over a long period of time without risk.

There are a considerable number of techniques that have been used successfully, but in order to obtain the best results, it is desirable to work with a patient and determine how the patient can best use his capacity for responding to suggestions. Although it is correct to speak about hypnotizability as a trait, and the generalization that hypnotizable individuals are vastly more capable of learning to suppress pain is certainly true, individuals also vary in the specific hypnotic skills that they can easily utilize. For example, given a pain in the right arm, one may first induce hypnosis and then suggest: "the arm is going to begin to feel numb, with a pins and needles sensation as though it had received novocain, and it will go entirely to sleep," and after a period of giving such suggestions, "this numbness is now so complete that there will be no pain sensation whatsoever, though you just might be able to barely feel my touch."

Such suggestions can be very effective and cause the patient not to feel any pain. Note that they utilize the subject's imagining sensations he has had in

853 HYPNOTIC METHODS FOR MANAGING PAIN

the past: numbness, pins and needles, the feeling that "novocain" has been injected, or that the arm had gone to sleep. Once he has been able to imagine these experiences, to the extent that he experiences them, he will also gain control over the pain sensation in that arm.

An entirely different approach would be to suggest that the arm float up, bending at the elbow, and then that the patient imagine the arm floating down again, that he can see that happening although I continue to hold the arm in the upright position. Once the patient experiences the arm back on his lap, he is likely to no longer feel the pain in the actual arm, which now does not seem to belong to him. This procedure, first discribed by Erickson, is an indirect way of suggesting away the pain by way of implicitly defining it outside of the body.

A different technique to achieve a similar aim is to have a patient imagine that he will be able to capture the pain in his left hand as he makes a fist. The tighter his fist is, the more the pain will be in his left hand, and once the pain is totally in his left hand, he will be able to throw it away and not have it return for several hours. This procedure takes advantage of the experience of focusing on the left hand the sensation of musculature tension and pressure to facilitate the response to suggestion. Again, one may have the patient relive an experience of 6 months ago -- prior to the pain in the arm --and thereby eliminate the discomfort.

Each of these procedures depends on the subject's ability to do some particular kind of hypnotic task, and the good clinician finds out which tasks are congenial to the patient and utilizes these to facilitate his response to suggestions.

SELF-HYPNOSIS

One of the procedures that has been particularly helpful in teaching patients how to control pain is training in self-hypnosis. Virtually everything an individual can experience in hypnosis can readily be taught to be experienced following self-induced hypnosis (2). Given a reasonably responsive subject, self-hypnosis can be taught fairly rapidly, and the patient then learns to practice the procedure in the therapist's absence.

There are a number of techniques to train patients in self-hypnosis. Most of them are reasonably effective, but little research has been done to show that one procedure is more effective than another. Worldwide, the technique most used is autogenic training (4), which has the virtue of being very systematic in the way it is taught over many sessions and often can be learned by individuals who are not initially as responsive to hypnosis as one might wish. On the other hand, given a responsive subject, autogenic training is unnecessarily drawn out, and within a single session a patient can learn to control his pain successfully.

Although self-hypnosis is exceedingly useful in the clinical situation, it is all

854 HYPNOTIC METHODS FOR MANAGING PAIN

too easy to assume that once the patient has learned the skill the therapist becomes superfluous. Of course, it is the implied theoretical assumption when we speak of self-hypnosis that the patient learns to administer the treatment himself. However, I have come to question this belief, although this does not prevent me from utilizing the technique to minimize the number of therapeutic sessions required.

When I first began to work with self-hypnosis, I saw a young patient with severe pain related to lesions of the spine, a pain that could not adequately be controlled by 100 mg of meperidine several times a day. She was fortunate to be able to enter deep hypnosis easily and quickly, and it was possible to show her how to induce self-hypnosis, which she rapidly learned to do, and thereby control her pain. It was agreed that she would use this technique to manage her pain and use medication only if she could not control it otherwise, and I arranged to see her a week later.

When she came for her appointment, she reported that she had been totally pain free for 5 days, but, during the sixth day, she found she could no longer control the pain adequately and needed a small amount of meperidine to control the pain. On the seventh day, she had become even less able to control the pain and required more of the narcotic to remain comfortable until she saw me that evening. I again induced hypnosis, went through the various selfhypnosis exercises with her, which she found much easier to do in my presence, and, after showing her some minor details of technique, woke her, had her try the self-hypnosis procedures again, satisfying myself that she could now reinduce trance at will, and again made an appointment a week hence.

When she was next seen, she reported the identical difficulty: that her ability to control pain tended to wear off over time. I again found her responsive and able to quickly reestablish her ability to induce self-hypnosis and control the pain. This time, however, I told her that I wanted to speak with her and check how things were going on the fifth day. We had a 5-min telephone conversation in which she indicated that she was doing well, describing how many times she had done her exercises and similar details. When she was seen 2 days later, she had had no need to use narcotics. By judicious use of brief telephone calls, I learned that it was possible to extend the time between visits to 2 weeks and eventually 3 weeks but that it was necessary for her to maintain contact with me by telephone or, at times, by letter in order for her skill at self-hypnosis to maintain itself.

Since then, I have noted that this is a common problem and routinely use brief telephone calls as a means of spacing interviews. It seems to me that this is an important observation, both conceptually and clinically. It would appear that self-hypnosis, in many instances at least, is dependent on a continuing relationship with the hypnotist, but that this relationship can be maintained fairly inexpensively to both patient and therapist. It is my suspicion that this mechanism is by no means limited to self-hypnosis and may play an important

855 HYPNOTIC METHODS FOR MANAGING PAIN

role in the management of many other supportive psychotherapeutic efforts in which a patient needs to practice some skill at home but at intervals requires the reassurance of the therapist. Conceptually, of course, it suggests that the boundaries between self-hypnosis and heterohypnosis are far less stringent than many of us have thought, an issue that sorely needs systematic investigation.

A final topic deserves discussion. Just as hypnosis may serve as a placebo, it is also true that therapeutic maneuvers may be used in the hypnotic context that have little to do with hypnosis itself but happen to fit into the way it is used. This is most dramatically illustrated in the treatment of terminal cancer. I am aware that the dominant school of thought believes that patients should be made aware of their illness and that they are better off facing their approaching death. Although this may be true with some patients, it is by no means true for all patients. Certainly, European medicine has not generally shared the same view, and many patients seem to prefer to ignore facts at their disposal that would indicate that they are suffering from a terminal process.

It is not my intent here to argue the best approach to the dying patient, merely to suggest that information can be provided in a way that allows the patient to know his condition if he chooses to know about it and permits him to deny the reality if he finds that an easier way to cope with feelings that few of us are equipped to cope with adequately. In this context, I have been impressed with the effectiveness of having patients who are terminally ill age regress and age progress to 1 year ago and to 2 years hence, living the experience in their minds, spending time with their family and friends at some resort where they had hoped to go, and so on.

Initially, I thought of this as a simple technique to indirectly suggest away discomfort and pain. The remarkable degree of relief this procedure gave to some patients suggested, however, that something else might be occurring. It became apparent that talking about the future in trance, or for that matter out of trance, is one of the most powerful ways of helping a patient to reestablish a defensive denial of his illness. Permitting, in a sense encouraging, such a denial seems to dramatically help some patients deal with the pain associated with the illness. I mention this to emphasize that we need to keep in mind that hypnosis may mobilize cognitive and affective mechanisms that relate to the experience of pain but that have little to do with the ability to enter hypnosis, although they may have profound effects on the patient's ability to cope.

SUMMARY

I have tried to emphasize that hypnosis may be used to help in the control of pain in a variety of ways. Although direct or indirect suggestions aimed at suppressing the pain experience are effective with highly hypnotizable subjects, these techniques should be used only if the etiology of the pain is clearly organic. The chronic pain syndrome or any kind of functional pain should not

856 HYPNOTIC METHODS FOR MANAGING PAIN

be treated by direct suggestion, although hypnosis may play some role in the context of dynamic psychotherapy to facilitate the uncovering of conflicts. Finally, self-hypnosis seems to be the most promising development in the treatment of pain by suggestive means. It is widely applicable and easily learned. However, the therapist should be aware that his relationship to the patient remains important, and the patient's continuing ability to control his pain by self-hypnosis may depend on his continuing contact with the therapist. It is suggested that hypnosis may be an effective adjunct in the treatment of pain provided the therapist understands that there are two quite different mechanisms by which hypnosis can be effective and appreciates the indications and contraindications for its use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The substantive research on which this paper is based was supported in part by Grant MH 19156 from the National Institute of Mental Health and in part by the Institute for Experimental Psychiatry.

REFERENCES

1. Evans, F. J. (1977): The placebo control of pain: A paradigm for investigating non-specific effects in psychotherapy. In: Psychiatry: Areas of Promise and Advancement, edited by J. P. Brady, J. Mendels, M. T. Orne, and W. Rieger, pp. 129-136. Spectrum, New York.

2. Hilgard, E. R., and Hilgard, J. R. (1975): Hypnosis in the Relief of Pain. William Kaufmann, Los Altos, California.

3. Hilgard, E. R., and Morgan, A. H. (1975): Heart rate and blood pressure in the study of laboratory pain in man under normal conditions and as influenced by hypnosis. Acta Neurobiol. Exp., 35:741-759.

4. Luthe, W. (1965): Autogenic Training: Correlations Psychosomatecae. Grune & Stratton, New York.

5. McGlashan, T. H., Evans, F. J., and Orne, M. T. (1969): The nature of hypnotic analgesia and the placebo response to experimental pain. Psychosom. Med., 31:227-246.

6. Shagass, C. S., Naiman, J., and Mihalek, J. (1956): An objective test which differentiates between neurotic and psychotic depression. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry, 75:461-471.

7. Sternbach, R. A. (1968): Pain: A Psychophysiological Analysis. Academic Press, New York.

Figure 1 (p. 849) (from Hilgard, E.R. & Morgan, A.H.

Heart rate and blood pressure in the study of laboratory pain in man under normal

conditions and influenced by hypnosis. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis, 1975,

35, 741-759) is reproduced here with the kind permission of the editor of the

Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis.