Martin T. Orne and David F. Dinges

INTRODUCTION

Hypnosis is among the oldest and best-documented psychological treatments for pain. From the controversial reports of its use in surgery prior to the development of chemoanaesthesia (Esdaile 1850), to the extensive experimental and clinical literature on its use during the past 30 years (see Hilgard & Hilgard 1975), hypnosis has been observed to provide almost total relief from the appreciation of pain in some individuals in a manner not attributable to mere relaxation, stoicism or fakery (Hilgard et al 1974). There is documentation of hypnosis as the sole anaesthesia during surgery including: temporal lobectomy, extraction of teeth, tonsillectomy, thyroidectomy, pulmonary lobectomy, cardiac surgery, removal of pedunculated folds, bilateral mammaryplasty, appendectomy, Caesarean section, hysterectomy, transurethral resection and excision of varicose veins (for reviews see Tinterow 1960, Scott 1973, Hilgard & Hilgard 1975, Finer 1980). Such cases clearly demonstrate that hypnosis can suppress pain, at least in some patients.

Beyond its surgical application, hypnosis is an effective analgesic for pain resulting from procedures such as the debridement of burns and bone marrow aspirations, as well as pain associated with illnesses such as arthritis and cancer. While the analgesic and anaesthetic effects of suggestions for pain reduction appear unequivocal for some individuals, the nature of hypnosis and the mechanism for these effects are less certain.

Hypnosis and suggestion

Controversy over the nature of hypnosis and its utility as a construct has existed since the phenomenon was first described. Regardless of whether it is theorised to be an altered state of consciousness, believed-in imagining, role enactment, fantasy absorption or focused attention, hypnosis is real in the sense that the individual believes in his experience and is not merely acting as if he did. Simply, hypnosis may be considered as that state or condition which occurs when appropriate suggestions elicit distortions of perception, memory or mood (Orne 1980).

Hypnotisability

The ability to experience suggested distortions varies considerably among individuals, but is not the same as compliance, conformity, gullibility or persuasibility. Some individuals are highly responsive to suggestions for altering their subjective experience, while others are not. This responsiveness dimension, called hypnotisability, shows some changes with age (Morgan & Hilgard 1973) or special circumstances (Barabasz 1982), but generally remains a remarkably stable attribute of the person throughout adult life (Morgan et al 1974). Hypnotisability is evaluated clinically by the individual's responsiveness to suggestions following induction and may be measured systematically by standardised tests (see Hilgard 1982).

As a stable attribute of the individual, hypnotisability has repeatedly been found to predict the efficacy of suggested analgesia in both experimentally-induced pain with (Hilgard et al 1975) or without (Spanos et al 1979) a hypnotic induction, and clinical pain of children (Hilgard & LeBaron 1982) and adults (Schafer 1975). The prediction, though reliable, is only modest, however, because overall responsiveness to suggestions is only imperfectly correlated with response to a specific suggestion, such as analgesia. Further, the response may be altered as a function of the context in which the suggestions are administered. Contributions of the context centre on the relationship between the subject and the therapist/hypnotist and include expectations, motivation, co-operativeness and trust--all of which may affect the individual's response to a hypnotic induction procedure.

Rapport and induction

The discovery of hypnotisability changed the thinking about hypnosis from the view that its effectiveness resided in the hypnotist to emphasis on the individual's hypnotic abilities. While investigators agree that the subject's ability to respond to suggestion is crucial, it is also clear that this responsiveness may readily be inhibited if the subject wishes to do so. Therefore, the establishment of a trusting relationship and the clarification of the limitations and goals for which hypnosis is to be used are essential to create the co-operative relationship in which responsiveness to suggestion is maximised. Once rapport is established, the administration of suggestions is usually done after a relatively brief hypnotic induction.

There are a large number of induction procedures, but

806

807 HYPNOSIS

most include instructing the individual to focus attention, to attend to the hypnotist, to relax, eventually to close the eyes and to imagine what the hypnotist is suggesting. (While relaxation suggestions are often used to induce hypnosis, physical relaxation is not necessary; in fact, suggestions of hyperalertness are equally effective, see Vingoe 1968.) The induction is a simple procedure requiring no drugs or other special techniques. The apparent trivial nature of this procedure juxtaposed against the dramatic effects subsequent suggestions can have upon some subjects' experiences has spawned much of the controversy surrounding hypnosis and its effects, the area of pain control being no exception (e.g. Chaves & Barber 1976).

Though hypnotic induction may serve to accentuate the response of hypnotisable individuals to certain hypnotic suggestions, it is neither a necessary condition for these effects, nor a sufficient condition to produce hypnotic phenomena in unhypnotisable individuals (Orne 1980). Consequently, it cannot be used to define hypnosis. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that an induction procedure defines the context as hypnotic for a subject, regardless of hypnotisability. This change in context, and the rapport that it is built upon, can bring about significant alterations in the interpersonal relationship between therapist and patient, which may have profound consequences on behaviour and experience. Though such changes are due to the hypnotic context rather than hypnosis per se, they are often an integral part of the use of hypnosis in therapy, such as in pain control where they may impact upon the reactive components of pain.

Hypno-anaesthesia and hypno-analgesia

The increased tolerance to pain in hypno-analgesia as well as the overt insensitivity to pain in hypno-anaesthesia might be thought to involve only reductions in what Beecher (1956) described as the reactive or suffering component of pain, without any appreciable elimination of pain sensation. The gist of this argument is that the individual utilising hypnoanaesthesia is simply very relaxed and not anxious about the surgical procedures or the painful sensations. Moreover, it is asserted that the intensely co-operative relationship with the hypnotist makes the patient reluctant to admit to felt pain (e.g. Barber 1963).

Though there clearly is an anxiety-reducing component to hypnosis in the control of pain, studies of pain induced under anti-anxiety drugs (Chapman & Feather 1973), of pain following hypnotic induction or relaxation instructions without suggested analgesia (Johnson 1974), of the relationship between subjective anxiety and felt pain under hypno-analgesia (Greene & Reyher 1972), and of pain and suffering reports from highly hypnotisable subjects (Knox et al 1974), do not support this view. Hypnosis is apparently more than just a tranquilliser in the relief of pain--affecting both the perceptual and reactive dimensions of pain--in appropriately responsive individuals.

Even unhypnotisable subjects appear to achieve some pain reduction in response to hypnotic suggestions, largely due to the nonspecific relaxation or fear-reduction component of the hypnotic context (Hilgard et al 1978). Their modest pain reduction is equivalent to their response to a drug placebo pain reliever (McGlashan et al 1969). This placebo component of hypnosis should not be underestimated, however, since it can be of major importance in allaying fears and tensions and increasing patients' coping skills before and after surgery under chemo-anaesthesia (Crasilneck & Hall 1975, Kroger 1977). It may even be greatly augmented during acute emergencies, much in the way that Beecher (1959) has described the dramatically increased efficacy of drug placebo for pain relief in such situations.

The alteration of pain perception in addition to reduced suffering in individuals of sufficient hypnotic ability does not result from the placebo component of the hypnotic context, but rather from the subject's response to specific suggestions for analgesia. This response may appropriately be conceptualised as a negative hallucination for pain and occurs because the individual is able somehow to alter the manner in which the sensory aspects of noxious signals are perceived. Interestingly, not only are analgesia suggestions necessary to achieve this alteration, but certain kinds of suggestions are maximally effective, particularly those that involve cognitive strategies that are antithetical to pain (Spanos et al 1975). Moreover, analgesia suggestions appear to be superior to strategies that emphasise only pleasant imagery (Green & Reyher 1972) or imaginative skills (Piccione 1980). These observations confirm the clinical view that suggestions for analgesia can take a variety of forms, but should somehow permit the patient to address the pain to be reduced within a framework that is both comfortable to the patient and maximises his hypnotic skills.

The attenuation of pain perception and experience in responsive individuals appears to occur at the higher levels of the nervous system. Often the individual successful at hypno-analgesia will report less felt pain relative to a time without analgesia suggestions. Only in an exceptionally responsive individual is pain ever completely absent and even when this is possible, it may not be wise to remove all of the pain in certain chronic organic pain patients (see Crasilneck & Hall 1975). Usually, highly responsive subjects will report that although pain was absent, pressure or tactile sensation of some sort was perceived.

The cognitive dissociation characteristic of successful hypno-analgesia in these individuals is illustrated by maintenance of involuntary physiological and behavioural responses to the pain during hypnosis, despite experiential comfort and alertness (Shor 1959, Bowers 1976). The presence of autonomic nervous system responses to pain in the absence of perceived pain during hypno-analgesia clearly indicates that the response is not peripheral. Even when suggestions of local anaesthesia with numbness and tingling are successfully induced, the centrally-mediated concomitants of pain persist.

In attempting to understand this phenomenon, one of the more exciting possibilities for a physiological basis of suggested analgesia was the discovery of endogenous endorphins. Unfortunately, of the half-dozen studies thus far carried out on this possibility, most show clearly negative results (see Nasrallah et al 1979).

In sum, the hypnotic context involves not only hypnosis but also a special relationship between subject and hypnotist

808 TEXTBOOK OF PAIN

and elements of relaxation, reassurance and the expectation of relief. Even individuals who have little or no skill in responding to hypnotic suggestions can derive some benefit from such procedures, which are best conceptualised as the placebo response of the hypnotic situation. However, hypnotisable individuals are able to show a much greater decrease in pain experience, which not only appears to be a specific response to suggestions of analgesia but also is related to the patient's ability to respond to other hypnotic suggestions. The physiology of these mechanisms, while clearly central in origin, has yet to be identified. Finally, hypnotic procedures also involve aspects such as distraction, which moderate the pain experience and which must be taken into account in assessing hypnotic control of pain.

Hypno-analgesia compared to other techniques of pain control

The benefits of hypnosis for pain control can be derived from a number of factors alone or in combination: 1. specific reductions in perceived pain and suffering in hypnotically responsive individuals, 2. reduced suffering due to nonspecific, placebo effects on relaxation and anxiety, and 3. moderation of pain perception through suggestions that involve distraction and other cognitive strategies that are not an essential aspect of hypnosis but which can nevertheless contribute to the attenuation of pain. Research has been conducted on the extent to which these processes account for hypno-analgesia relative to other psychological and physiological techniques for pain relief.

In this regard, acupuncture has been extensively compared to hypnosis. Though the initial studies suggested that hypnotisability accounted for some of the effect of acupuncture analgesia, subsequent investigations have not supported this conclusion (see Knox et al 1981). Not only are hypno-analgesia and acupuncture analgesia apparently different processes, but when compared, hypnotic suggestions appear to produce greater pain relief for both experimental (Stern et al 1977) and clinical (Ulett et al 1978) subjects than acupuncture or placebo acupuncture.

In a number of studies on a heterogeneous group of chronic pain patients, Elton and colleagues (1980) compared the pain control efficacy of hypnosis to that of behavioural psychotherapy, EMG biofeedback and drug placebo. While all other treatments were superior to drug placebo, hypnosis was somewhat more effective than psychotherapy and equally as effective as biofeedback, though the latter was more difficult than hypnosis for patients to transfer from the clinic to the real world. Hypnosis has been reported to be somewhat more effective than EEG alpha biofeedback for pain relief in some chronic pain patients, but the two procedures combined were most effective (Melzack & Perry 1975).

Numerous studies have included relaxation treatments for pain control relative to hypno-analgesia, as well as drug placebo conditions. Hypnosis has consistently proven more effective than these non-specific treatment approaches. Only in unhypnotisable subjects does the magnitude of pain reduction, following hypnotic induction procedures and suggestions of analgesia, correspond to the magnitude of reduction under drug placebo (McGlashan et al 1969).

Beyond this, however, hypnosis has been reported to be more effective in reducing experimentally-induced pain in normal individuals relative to morphine, aspirin, and an active tranquilliser (Valium) (Stern et al 1977). Consistent with other studies, the superiority of hypnosis was greatest for highly hypnotisable individuals. This same study reported that the pain reduction response to morphine was somewhat higher for more hypnotisable subjects, relative to unhypnotisable subjects. In a study of acute dental pain, the effectiveness of hypnosis was again clearly related to patients' hypnotisability, but pain ratings were lower overall under local chemo-anaesthesia than with hypnosis. Nevertheless, highly hypnotisable patients preferred hypno-analgesia (Gottfredson 1973).

It is difficult to come to any firm conclusions regarding the comparisons of hypno-analgesia to other pain relief treatments because so many factors can affect the results and generalisability of the results from any one study. Among the more crucial parameters are the type of subjects used and the nature of the pain, the type of research design, the expectations of the experimenters, the manner in which hypnotisability and pain are assessed, the assignment of subjects to treatments, the base level of pain, of anxiety and of coping ability of the subjects.

In terms of understanding hypno-analgesia, aspects of the pain and the patient population are particularly relevant to interpreting experimental results. For example, it is possible that the experiences, motivations, expectations and perhaps even hypnotisability of many pain patients may be different from the equivalent characteristics of laboratory subjects. A factor that is relatively non-contributory to pain relief in laboratory subjects may be considerably more important in suggested analgesia in patients. Finally, the nature of the pain, its aetiology, time course, severity and meaning to the patient are crucial in determining the appropriateness of direct hypnotic suggestion in the relief of pain.

APPLICATIONS OF HYPNOSIS IN PAIN RELIEF

Hypnosis has been used for a wide range of pain conditions, covering both the acute-chronic and the organic-functional spectrums. In these applications it is necessary to distinguish between hypnosis used as a technique to give direct suggestions for the relief of pain, hypnosis used to facilitate the psychotherapeutic treatment to help the patient gain understanding as to the meaning of the pain and thereby achieve mastery over it, and hypnosis to facilitate the behavioural treatment of pain. The application of hypnosis to these latter two areas is not directly for the relief of pain, but rather ancillary to a broader psychological approach to the treatment of pain behaviour. Thus, indications and contraindications for the use of hypnosis in the context of psychotherapy and behaviour therapy are those of these therapies and will not be discussed here. Instead, the focus will be on hypnosis for direct suggestion of pain relief.

In this context, it is essential to recognise that because a patient responds to hypnosis for pain relief does not mean

809 HYPNOSIS

that the pain has a psychological aetiology. Similarly, the psychological nature of hypnosis as a treatment for pain through direct suggestion does not mean that it is to be used for pain of functional origin. Paradoxically, the opposite is generally true.

Direct hypnotic suggestions to reduce pain are safe and appropriate for pain of organic aetiology. The more ambiguous the aetiology of pain and the more pain behaviour becomes an integral part of the patient's functioning, the less likely that direct suggestions of pain analgesia will yield enduring relief and the more likely that they will rapidly become ineffective or result in symptom substitution (Orne 1983). This point will be elaborated on in terms of chronic pain syndrome, after a discussion of the applications of hypnosis to acute and persistent pain of known organic aetiology.

Acute pain of organic aetiology

Both hypno-analgesia and hypno-anaesthesia have been employed in the treatment of acute pain of physical origin. The most clear-cut application involves pain induced as part of a procedure such as dentistry, surgery, bone-marrow aspirations, the changing of burn dressings and so forth. Others involve transient, painful events such as childbirth, acute sprains or fractures, Herpes zoster and the like.

The amount of pain relief does not only depend upon hypnotic responsiveness but also is related to the kind of pain and the context in which it occurs. Thus, it is not uncommon to find a report that over 90% of patients achieved some appreciable degree of pain relief when hypnosis was used in a dental procedure (Barber 1977), compared to estimates that less than 10% of patients can effectively use hypnosis for pain control in minor surgery, and possibly fewer than 1% in major intra-abdominal surgery (Marmer 1963). When estimates are extremely high, the pain is likely to be non-threatening and not too intense or prolonged, with placebo components and distraction contributing in a major way to the results.

Surgery

While a wide range of examples exist of major and minor surgical procedures being carried out solely with hypnoanaesthesia, no one recommends the exclusive use of hypnoanaesthesia for surgery today, unless the patient is at serious risk from chemo-anaesthesia or must be conscious during surgery (Crasilneck & Hall 1975). The way hypnosis is commonly used in anaesthesia is to reduce anxiety and fear prior to surgery, to decrease the amount of chemo-anaesthesia required during surgery, and to reduce the intensity and duration of post-operative pain.

The liberal use of suggestions for relaxation, comfort, confidence and post-operative pain reduction can contribute substantially to an overall reduction of anxiety and discomfort surrounding surgery for many patients (Marmer 1963, Erickson 1979). For unhypnotisable patients, such benefits are largely a result of the increased pre-operative encouragement and reassurance from the physician (see Egbert et al 1964) rather than due to suggestion per se. Nevertheless, this illustrates an often ignored consequence of using hypnosis for pain. The restructured physician/patient relationship becomes more intense and the patient's comfort is affected by this increased rapport.

Post-hypnotic suggestions to relieve post-operative pain are often administered prior to and during surgery. Though many practitioners report that hypnosis is helpful for post-operative pain, few systematic investigations have been reported objectively studying this effect of post-hypnotic suggestion.

Burns

Experimental data suggest the intriguing possibility that hypnosis may provide some protection against burn reaction to a standard heat stimulus (Chapman et al 1959). More recently an analogous possibility has also been proposed in the clinical literature (Ewin 1979). The most compelling use of hypnosis in the treatment of burns, however, has been to control the pain inevitably produced by the redressing and debridement of the wounds. The acute, intense pain associated with these repetitive procedures generally becomes traumatic for both patient and personnel alike. A number of systematic studies and case reports have been published detailing the efficacy of analgesia suggestions and ego-strengthening procedures through hetero-hypnosis and self-hypnosis (Margolis & De Clement 1980). Based upon these reports it appears that a surprisingly high proportion of burn patients (60-90%) who use hypnosis achieve substantial relief from pain.

The effectiveness of hypno-analgesia for pain from burn redressing has been reported to be positively associated with hypnotisability (Schafer 1975). Hypnosis has also been shown to reduce the amount of medication required by burn patients when the extent of burn and amount of supportive contact were controlled (Wakeman & Kaplan 1978). Unexplained is the remarkably high proportion of burn patients who appear to be hypnotisable (Margolis & De Clement 1980). This may be due to the desperation and high motivation for pain relief characteristic of this population (Crasilneck et al 1955). It appears that only the very unhypnotisable patients and those with serious emotional problems (that prevent the establishment of rapport) are unable to use hypno-analgesia for the reduction of burn pain.

Dentistry

The use of hypnosis for acute pain relief in dentistry typically involves suggested analgesia within the confines of a relatively brief dental procedure. Given the availability of convenient and highly effective local anaesthetics, hypnosis is rarely used alone. As in surgery, however, allergies to chemo-anaesthesia have prompted its successful application as the sole analgesic (Morse & Wilcko 1979). A carefully controlled clinical study comparing hypno-analgesia to chemo-anaesthesia in the relief of dental pain found that hypnosis was clearly more effective in hypnotisable patients (Gottfredson 1973). In a controversial study, Barber (1977) reported no relationship between hypnotisability and a Rapid Induction Analgesia procedure that he developed for use in

810 TEXTBOOK OF PAIN

dentistry. 99% of his patients are reported to have completed their dental procedure without the aid of any chemical anaesthesia. This remarkable success rate has not thus far been adequately explained or replicated.

One of the more common uses of hypnosis in dentistry involves its application to patients who suffer a serious phobia for dental pain and dental procedures. There is some evidence of a positive relationship between the intensity of dentaphobia and the degree of hypnotisability (Gerschman et al 1979). Further, hypnosis can be quite effective helping phobic patients tolerate an injection of novocaine, which involves a low level of actual pain and not surprisingly leads to reports of very high levels of success. In cases of very severe dentaphobia, hypnosis has also been used successfully as the sole analgesic (Crasilneck et al 1956). While hypnotic responsiveness appears to contribute significantly to the effectiveness of hypno-analgesia, reassurance and nonspecific factors probably account for much of the benefit of hypnosis in routine dental procedures with moderately anxious individuals (McAmmond et al 1971).

Obstetrics

Concern over the potentially harmful effects of analgesic and anaesthetic drugs on the unborn child has motivated much of the interest in the use of hypnosis in obstetrics. Like other antenatal childbirth preparation techniques, hypnosis is typically used to reduce anxiety and control the pain and discomfort associated with labour and delivery as well as postnatal pain (e.g. due to episiotomy). Hypnosis has been reported to have been used successfully in a high proportion of obstetric cases, including patients who have had no prior preparation (August 1961).

Though some studies have been conducted comparing hypnosis to other antenatal procedures, its superior effectiveness for pain reduction in labour and delivery has not been demonstrated. As Davenport-Slack (1975) noted, hypnosis as well as all other antenatal techniques place considerable emphasis on relaxation and anxiety reduction. Moreover, distinctions between hypnosis and the various techniques are at times blurred, because most involve suggestions for appropriate behaviour in response to the experience of labour and delivery pain, as well as the use of cognitive strategies to minimise pain.

While reports of the efficacy of hypnosis have not included estimates of hypnotisability, it is recognised that full obstetric pain reduction with no chemical analgesia or anaesthesia being required is possible for only about 20% of cases (Kroger 1977)--an estimate consistent with what is known about the distribution of hypnotic responsiveness in the general population. Hypnosis is nonetheless useful and advantageous for the vast majority of patients (Stone & Burrows 1980). It is a highly efficient and flexible procedure which can be readily carried out in groups, with all but a very small proportion of individuals reporting considerable benefit from it and requiring less pain medication.

Other acutely painful medical procedures

The use of hypnosis in the four areas reviewed above is typical of the treatment of acute pain of clear organic aetiology and the approach can be generalized to a myriad of similar applications. A study of one of these areas, involving acute pain due to bone-marrow aspirations in children with leukaemia, is not only an example of such an application, but illustrates the complexities of clinical research in this field.

Bone-marrow aspirations are required on a regular basis from leukaemia patients in order to monitor the course of the disease. Hilgard & LeBaron (1982) have recently reported the successful use of hypnosis to relieve the pain due to aspiration in 15 of 24 children ranging from 6-19 years of age.

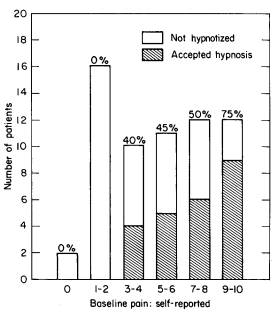

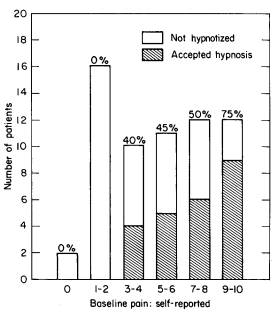

This model clinical study included a number of novel methodological aspects. Most relevant was the careful baseline evaluation of the child's pain response during bone-marrow aspiration. It was found that close to 30% of all children spontaneously employed effective cognitive strategies to reduce pain almost totally during the procedure. These children did not volunteer for hypnosis. In fact, the higher the baseline pain report, the greater the likelihood that a child would volunteer for hypnosis (see Fig. 252). It is worth noting that if hypnosis had been applied routinely to all 63 children, without baseline measures of pain, it would have been erroneously assumed that these children with very little or no baseline pain had been helped by hypnosis.

Interestingly, within those 24 children who had volunteered for hypnosis to relieve the pain of the procedure, there was a clear relationship between hypnotisability and

Fig. 252 The number of leukaemia patients (children) selecting hypnosis for control of pain due to bone-marrow aspiration (from Hilgard & LeBaron 1982). Patients are divided according to the severity of their self-reported pain during baseline (no hypnosis). A total of 63 children were observed and offered hypnosis, and 24 accepted it. Percentages above each bar (as well as shaded sections) are the proportion of patients with a particular baseline pain rating who accepted hypnosis. As is evident, the higher the baseline pain, the more likely it was that the child would be willing to try hypnosis.

811 HYPNOSIS

the amount of pain reduction achieved: hypnosis was generally more effective for those patients with higher hypnotisability. Further, some of the unhypnotisable children, though unable to reduce pain with hypnosis, achieved anxiety-reduction and had less observable pain behaviour due to the relaxation and psychotherapeutic components of the hypnotic intervention. It would appear that hypnosis has much to offer children experiencing acute pain.

Persistent pain of organic aetiology

While it may seem that the application of hypnosis for relief from persistent pain of organic aetiology would be as straightforward as its use in acute pain, this is not necessarily the case. The mere fact that a pain persists, even though it has an unequivocal organic basis, can mean that it has acquired functional significance in the context of the individual's adjustment. Thus, persistent pain can result in psychological as well as physical consequences for the patient, and both of these must be taken into account when treating such pain with hypnosis. A distinction should be made between hypnosis for the direct treatment of the pain and hypnotherapy for treating its emotional ramifications. The use of hypnosis in the treatment of pain due to terminal illness provides a clear illustration.

Terminal cancer

Though not all terminal cancer patients have pain, many do, and the pharmacological treatments for such pain either are not always effective or create serious secondary complications for the patient's functioning. Thus, there are clear advantages to the patient achieving some degree of psychological control over the persistent debilitating pain resulting from the disease. Butler (1955), Erickson (1967), Sacerdote (1970) and Gardner (1976) provide excellent examples of the use of hypnosis in the treatment of terminal illness. Their approaches serve to illustrate the need to distinguish between hypnosis for pain and hypnosis for coping with the emotional consequences of the disease and the pain resulting from it.

There are no easy guidelines to determine precisely how much of a given terminal cancer patient's persistent pain is a function of physical factors and how much of it may reflect a psychological response to the disease and to the predicament of the patient. Among the factors that enter into terminal illness and interact with the pain are: a decreased feeling of control over one's destiny, a diminished ability to cope with stress, the need to depend upon others, the realistic fear of death, the intrusive consequences of malignancy and certain medical procedures directed at destroying it and changes in the relationship with friends and loved ones. It has frequently been noted that the terminal cancer patient becomes isolated as those close to him find it increasingly difficult to interact with him due to their own feelings of helplessness. Unfortunately, this may also include the family physician.

While the pain of terminal cancer may have a clear, organic basis (though often not as clear as one assumes), it is necessary not only to treat the pain qua pain, but also to consider the meaning of the psychological intervention for helping the patient cope with the pain. There is little doubt that hypnosis can prove highly effective in permitting some terminally ill patients to gain control over persistent, acute pain, particularly if the patient is highly hypnotisable (Cangello 1961).

The benefits, however, go beyond the reduction of pain. By being sensitive to both the organic pain and its meaning to the patient, the use of hypnosis can, for example, also increase the patient's sense of control over the pain (if not the disease), can help the patient achieve increased interpersonal satisfaction and, if desired, can allow the patient to deny the disease and thereby remain comfortable and more sanguine about the future. The application of hypnosis to the terminally-ill patient with persistent pain goes well beyond mere pain control, dealing also with the psychological and emotional significance of the disease and pain to the person.

Other persistent organically-based pain

Though other forms of disease that produce pain with a relatively clear organic aetiology may not be terminal, as with cancer, the persistent nature of the pain can cause it to acquire a functional role in the adjustment of the patient. Indeed, psychological complications can be even worse with such pain because the organic aetiology may be somewhat less certain than in cancer, and because the individual may have to cope with the disorder over a much longer period of time due to its non-terminal nature. Persistent pain associated with rheumatoid arthritis, head trauma, trigeminal neuralgia and back and bone problems with a definite physical basis are examples in this area.

The pain that is common to these disorders may not adequately respond to non-narcotic analgesics, and the use of narcotics in these conditions is contraindicated. Hypnosis has proven effective in reducing persistent pain for some patients with these disorders--usually the more hypnotisable individuals (Cedercreutz et al 1976). Nevertheless, the treatment of pain with hypnosis is generally only one aspect of the therapeutic intervention (Cioppa & Thal 1975, Crasilneck 1979). Again, hypnosis for the control of the pain must be distinguished from hypnosis within a psychotherapeutic or behavioural approach designed to help the individual cope more effectively with the disorder and pain. Often this latter approach has a more profound and lasting impact on the intensity and quality of the persistent pain.

Chronic pain of uncertain aetiology

Persistent pain with an ambiguous aetiology usually has major functional factors complicating its treatment (see Orne 1983 for a discussion). This area comprises much of what is considered the chronic pain syndrome, including such conditions as quasi-continuous tension or migraine headache, many of the low-back pain cases and a variety of chest, abdomen and limb pains. (Migraine headache is commonly believed to be caused by vasodilation and abnormal cerebral blood flow; however, there is evidence that it can be a psychosomatic disorder, suggesting that a purely

812 TEXTBOOK OF PAIN

physical explanation for the attacks may in some cases inadequately account for their aetiology). Typically the pain is very real to the patient, and in this sense it is no different from pain that has a clear, organic basis. However, unlike persistent physical pain, the chronic pain syndrome involves characteristic pain behaviour usually related to secondary gain, and may be associated with depression, masochism and a variety of complex emotional needs. These may serve to maintain the pain behaviour, or amplify the response to organic pain. This is not malingering or faked pain; the patient actually hurts and rarely has any insight into the cause of the pain.

Compared to patients with organically-based persistent pain, these ‘pain-prone’ individuals often have personality problems and irrational thought patterns. When the personality or thought pattern problems are treated (with hypnosis as part of the treatment), these patients respond somewhat better than when only the pain is treated with hypnosis (Elton et al 1980, Howard et al 1982). This is hypnotherapy, however, rather than hypnosis directed at only pain reduction. Though some reports of successful pain reduction exist for the use of hypnosis for migraine headache pain, for instance, the studies and case reports are inconclusive in terms of mechanism; placebo factors and behavioural interventions accompanying the use of hypnosis probably account for some of the reported effects.

In many individuals with chronic pain syndromes, the most appropriate treatment depends upon behavioural management so that the contingencies associated with manifesting the pain response are no longer desirable. As long as the pain response is rewarded (i.e. provides secondary gain), either by a pension which is greater than the patient could earn on his own or by attention and caring which he feels he cannot obtain in other ways, the likelihood of relieving the chronic pain syndrome is slim indeed (Block et al 1980).

Hypnosis is not the appropriate treatment for such functional pain (despite the fact that both the pain and hypnosis are psychological), because it has been shown not to be an effective means of causing an individual to modify behaviour that he is not ready or willing to modify--behavioural control through hypnosis is not effective in the treatment of behavioural disorders in general (see Wadden & Anderton 1982 for a review). Hypnosis is a viable technique to modify an individual's experience. Consequently, it is possible to block the appreciation of pain, but when one is dealing with a syndrome in which a major factor involves the consequence of pain behaviour--where the patient is rewarded for demonstrating his suffering--hypnosis is not likely to provide more than transient relief, with symptom substitution a distinct possibility.

HOW HYPNOSIS IS UTILISED IN SPECIFIC PAIN RELIEF

Hypnosis should not be considered the treatment of last resort for pain, though it is often used for chronic pain that has been refractory to other medical interventions. Of course, as noted above, this is precisely the type of pain for which hypnosis (in the form of direct suggestion) should probably not be used. The early application of hypnosis to organically-based pain, particularly acute pain, is, on the other hand, very appropriate. Not only will most patients benefit from relaxation and anxiety-reduction in the hypnotic context, but a substantial portion of them have the capacity to actually reduce the amount of felt pain. Some failures are to be expected, but if the application of hypnosis is properly structured, maximising both specific and nonspecific effects, most subjects will experience less discomfort in the acute pain situation. Suggestions will usually serve to reduce the amount of chemo-anaesthesia or chemo-analgesia required by patients, such as in surgery. If there is concern about use of the word ‘hypnosis’, this can be avoided by providing the hypnotic context and suggestions without using the term (Erickson 1979). However, it is often considered better to use the word as a lead-in for discussing the patient's beliefs about hypnosis, thereby facilitating the establishment of rapport by correcting misconceptions and informing the patient of the possibilities and limitations of the technique.

Preconditions for hypnosis

The establishment of rapport, as discussed above, begins the hypnotic intervention. However, prior to this it is essential to be certain that the patient has no physical or psychological problem that would make the application of hypnosis inappropriate. Suffice it to say that the pain condition should be evaluated medically before a psychological intervention is applied, and that the therapist should interact enough with the patient ahead of time to be certain that neither emotional disturbance (e.g. depression) nor psychotic problems (e.g. paranoia) exist.

Beyond this, however, it is necessary to learn the patient's motivation for seeking pain relief. As was suggested above, some of the dramatic effects of hypnosis for burn debridements may well relate to the motivation due to the intense pain that burn patients feel. Many clinicians consider motivation to be as important as hypnotic responsiveness, if not more so, in predicting the patient's ability to derive bona fide pain relief from hypnotic suggestions. This is an area where additional research is needed because it involves a major difference of opinion within the field concerning the mechanism of hypnotic pain relief.

In addition to patient motivation, it is important to determine one's own goals in treating the patient. While the treatment of acute pain with hypnosis for analgesia or anaesthesia is appropriate and safe in the hands of professionals (such as general practitioners, anaesthesiologists, or dentists) who are used to inducing chemo-anaesthesia, hypnosis can also provide access to serious deep-seated conflicts that are being superficially coped with by the patient. The use of hypnosis for uncovering these conflicts is a psychotherapeutic intervention rather than a pain-relief procedure. While physicians and dentists are experienced in providing support to patients and dealing with minor psychiatric problems in this fashion, they are not usually experienced in uncovering techniques for intensive psychotherapy. Hypnosis may facilitate the rapid development of intense transference reactions and bring to the

813 HYPNOSIS

surface psychological material with which the patient cannot cope. Experience with hypnosis per se is adequate background to give direct suggestions for relief of organic pain, but should not be confused with training in psychotherapy, which is essential to deal with the problems that can arise when uncovering techniques are employed.

The establishment of rapport is the sine qua non before proceeding with hypnotic induction, and generally involves the major portion of time with the patient. Induction itself is a relatively brief procedure once adequate rapport exists. There are literally hundreds of induction procedures used today. However, as discussed above, most are similar in their emphasis on relaxation and focused attention on the therapist's voice. There is very little evidence documenting the greater effectiveness of any one induction technique, and there is some question about the extent to which a formal induction procedure really matters in achieving hypno-analgesia in the hypnotisable patient.

In terms of induction and the administration of suggestion, one major change has occurred over the past 50 years. This has been the transition from an authoritarian relationship between hypnotist and subject to a cooperative, partnership relationship--the hypnotist as guide (Hilgard & Hilgard 1975). Most modern techniques of hypnosis focus on how this co-operative relationship is established vis-a-vis many people's stereotypes of an authoritarian relationship. The co-operative model fits comfortably into contemporary views of hypnosis, treatment and patient rights. It should be recognised, however, that some acutely-ill patients may need to have the doctor take the responsibility for pain relief. When this is the case, induction using a more authoritarian approach may be helpful, since it can utilise the regressive aspects of the patient's response to illness to facilitate pain control.

Specific techniques of hypnosis for pain control

A description of techniques for applying hypnosis to the control of pain goes well beyond the scope of this chapter because the type of pain, the context in which the hypnosis is to be applied, the goals and skills of the therapist using hypnosis and the expectations, motivations and responsiveness of the patient very much determine the specific manner in which hypnosis is best used to relieve pain. Rather than focus on specific treatment styles, it is more important to recognise those factors that directly determine the adequacy and appropriateness of hypnotic suggestions for pain relief. We have already noted that direct hypnotic suggestion is most appropriate for control of pain of organic aetiology, and that it is likely to be maximally effective in individuals with high hypnotic responsitivity.

Given adequate rapport, a motivated subject capable of at least a modest response to suggestion, and a suitable hypnotic induction, suggestions designed to relieve the pain can be administered. There are a variety of techniques for suggesting analgesia or anaesthesia. The application of any one of them requires the therapist to determine which suggestion style will maximise the patient's response. For some patients in some situations this will not matter; however, for others this will make considerable difference in the extent to which the patient can achieve hypno-analgesia or hypnoanaesthesia. In order to obtain the best results, it is desirable to determine how the patient can best use his capacity for responding to suggestions.

Although it is correct to speak about hypnotisability as a trait, and the generalisation that hypnotisable individuals are vastly more capable of learning to suppress pain is certainly true, individuals also vary in specific hypnotic skills that they can easily utilise. For example, given a pain in the right arm, one may first induce hypnosis and then suggest: ‘the arm is going to begin to feel numb, with a pins-and-needles sensation as though it has received novocaine, and it will go entirely to sleep’, and after a period of giving such suggestions, ‘this numbness is now so complete that there will be no pain sensation whatsoever, though you just might be able to barely feel my touch’.

Such suggestions can be very effective and cause the patient not to feel any pain. Note that they utilise the subject's imagining sensations he has had in the past: numbness, pins and needles, the feeling that novocaine has been injected and that the arm had gone to sleep. Once he has been able to imagine these experiences, to the extent that he experiences them, he will also gain control over the pain sensation in that arm.

An entirely different approach would be to suggest that the arm float up, bending at the elbow, and then that the patient imagine the arm floating down again, that he can see (hallucinate) that happening though the therapist holds the (real) arm in the upright position. Once the patient experiences the (hallucinated) arm back on his lap, he is likely no longer to feel the pain in the actual arm, which now does not seem to belong to him. This procedure, first described by Erickson (1967), is an indirect way of suggesting away pain by implicitly defining it outside of the body.

A different technique to achieve a similar result is to have a patient imagine that he will be able to capture the pain in his left hand as he makes a fist. The tighter his fist is, the more the pain will be in his left hand, and once the pain is totally in his left hand, he will be able to throw it away and not have it return for several hours. This procedure takes advantage of the experience of focusing on the left hand the sensation of muscular tension and pressure to facilitate the response to suggestion. Again, one may indirectly eliminate pain by having the patient relive an experience of 6 months ago-- before he had developed pain in his arm.

Each of these procedures depends upon the subject's ability to do some particular kind of hypnotic task; the good clinician finds out which tasks are easy for the patient and utilises these to facilitate his response to therapeutic suggestions. Hilgard (1980) discusses adapting a particular technique to the patient and structuring the situation to obtain the maximum pain relief, even for a relatively unhypnotisable subject. Many accomplished therapists who use hypnosis for treating patients in pain have published detailed descriptions of their techniques and the options available to the therapist. Examples of various techniques include the work of Stone & Burrows (1980) in obstetrics, Thompson's (1963) applications in dentistry, a chapter in Gardner & Olness (1981) on hypnotic techniques for pain relief in children, and a paper by Sacerdote (1980) updating his

814 TEXTBOOK OF PAIN

techniques for terminally-ill patients. Techniques are also reviewed in the books of Scott (1974), Crasilneck & Hall (1975), Hilgard & Hilgard (1975), Kroger (1977), Spiegel & Spiegel (1978) and in numerous case reports and review articles in the American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, as well as the International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis.

Self-hypnosis

One procedure that has proven helpful in teaching patients to control pain, particularly persistent, acute pain, is training in self-hypnosis. Self- or auto-hypnosis is possible even for patients with modest hypnotic ability. Virtually everything an individual can experience in hypnosis can be taught to be experienced following self-induced suggestions.

The learning of self-hypnosis involves the therapist teaching the patient to employ pain-reducing suggestions and strategies that the patient is comfortable using. Given a reasonably responsive subject, self-hypnosis can be taught fairly rapidly, which the patient then practises in the therapist's absence, thereby reducing the cost in time to both the therapist and patient.

There are a number of techniques to train patients in self-hypnotic pain control, depending upon the type of pain and characteristics of the patient (Gardner 1981, Sacerdote 1981). Most techniques are reasonably effective, but little research has been done to show that one procedure is more effective than another. Worldwide, the technique most used is autogenic training (Luthe 1965), which has the virtue of being very systematic in the way it is taught over many sessions and often can be learned by individuals who are not initially responsive to suggestions. On the other hand, given a responsive patient, autogenic training can be unnecessarily lengthy. With other self-hypnosis techniques a responsive patient can learn to control pain successfully within a single session.

Self-hypnosis is exceedingly useful in permitting many patients to develop mastery over their pain, thereby also providing an increased feeling of self-control that is often therapeutic. Because of this initial success, it is sometimes assumed that once the patient has learned the skill, the therapist becomes superfluous. This is based on the theoretical view that the patient learns to administer the treatment totally independent of his relationship with the therapist. This assumption has been questioned, however, because it turns out that often patients require periodic contact with the therapist to maintain the extent of pain relief possible under self-hypnosis (see Orne 1983). Therapists who have noticed this problem deal with it practically by maintaining occasional telephone contact or follow-up with their patients who use self-hypnosis (Crasilneck & Hall 1975, Hilgard & Hilgard 1975). This is consistently reported to be enough to facilitate the efficacy of self-hypnosis in pain control.

This problem of maintaining the benefits of self-hypnosis for pain control over a sustained time course raises serious questions about the relative importance of self-hypnosis training for pain reduction as opposed to the quality of the patient/therapist relationship. It seems that this latter factor may be essential for maintenance of self-control over pain, at least initially. Investigation of this area holds considerable promise for elucidating the factors most necessary to effectively and efficiently provide the maximum amount of pain relief to patients.

SUMMARY

Hypnosis has been used extensively in the control of pain in the form of hypno-analgesia or hypno-anaesthesia, both alone and as an adjunct to chemical pain reduction. Its effects on pain derive from the specific hypnotic responsiveness of the patient, as well as from the nature of the suggestions administered, and may be moderated by the patient's motivation and the intensity of pain being experienced. Both the sensory and reactive components of pain are affected in hypnotisable individuals, while non-specific or placebo factors that reduce primarily reactive aspects of the pain account for much of the effect of hypnosis on relatively unhypnotisable subjects. The factors that account for the effectiveness of hypnosis in pain control, though partially overlapping, do not appear to be the same as those of acupuncture, biofeedback, drug placebo, analgesics or tranquillisers. The effects of hypnotic suggestions for pain reduction are mediated at a high level of the nervous system by mechanisms that are not yet understood.

Though appropriate for acute pain (e.g. surgery, burn debridements, bone-marrow aspirations) or persistent pain of unequivocal organic aetiology (e.g. cancer, arthritis), hypnosis solely for the reduction of pain is rarely appropriate for functional pain (e.g. migraine or low-back) or organically-based pain that involves extensive secondary gains. The application of hypnosis to pain typically requires the establishment of rapport, an induction procedure and the administration of suggestions that permit the patient to achieve the maximum pain relief possible--this depends upon the hypnotic responsiveness of the patient as well as the skill of the therapist in understanding the patient's pain, cognitive skill and coping capacity. Often self-hypnosis techniques are useful to allow the patient to gain control over his pain. The success of this transfer of control from therapist to patient, at least initially, appears to depend upon the quality of the relationship between them as much as it does upon the hypnotisability of the patient.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The review and evaluation upon which the substantive theoretical outlook presented in this paper is based was supported in part by grant No. MH 19156 from the National Institute of Mental Health, US Public Health. Service and in part by the Institute for Experimental Psychiatry. This work was conducted at the Unit for Experimental Psychiatry of The Institute of Pennsylvania Hospital and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania Medical School. We are grateful to Emily Carota Orne for valuable suggestions and review of the paper, and to Stephen R. Fairbrother and Mary F. Auxier for help in preparing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

August R V 1961 Hypnosis in obstetrics. McGraw-Hill, New York Barabasz A F 1982 Restricted environmental stimulation and the

815 HYPNOSIS

enhancement of hypnotizability: Pain, EEG alpha, skin conductance and temperature responses. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 30: 147-166

Barber J 1977 Rapid induction analgesia: a clinical report. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 19: 138-147

Barber T X 1963 The effect of ‘hypnosis’ on pain: a critical review of experimental and clinical findings. Psychosomatic Medicine 24: 303-333

Beecher H K 1956 Relationship of significance of wound to pain experienced. Journal of the American Medical Association 161: 1609-1613

Beecher H K 1959 Measurement of subjective responses: quantitative effects of drugs. Oxford University Press, New York

Block A R, Kremer E, Gaylor M 1980 Behavioral treatment of chronic pain: variables affecting treatment efficacy. Pain 8: 367-375

Bowers K S 1976 Hypnosis for the seriously curious. Brooks/Cole,Monterey, Cal

Butler B 1955 The use of hypnosis in the care of the cancer patient (Part III). British Journal of Medical Hypnotism 6: 9-17

Cangello V W 1961 The use of the hypnotic suggestion for relief in malignant disease. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 9: 17-22

Cedercreutz C, Lahteenmaki R, Tulikoura J 1976 Hypnotic treatment of headache and vertigo in skull injured patients. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 24: 195-201

Chapman C R, Feather B W 1973 Effects of diazepam on human pain tolerance and pain sensitivity. Psychosomatic Medicine 35: 330-340

Chapman L F, Goodell H, Wolff H G 1959 Changes in tissue vulnerability induced during hypnotic suggestions. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 4: 99-105

Chaves J F, Barber T X 1976 Hypnotic procedures and surgery: a critical analysis with applications to ‘acupuncture analgesia’. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 18: 217-236

Cioppa F J, Thai A D 1975 Hypnotherapy in a case of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 18: 105-110

Crasilneck H B 1979 Hypnosis in the control of chronic low back pain. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 22: 71-78

Crasilneck H B, Hall J A 1975 Clinical hypnosis: principles and applications. Grune & Stratton, New York

Crasilneck H B, Stirman J A, Wilson B J, McCranie E J, Fogelman M J 1955 Use of hypnosis in the management of patients with burns. Journal of the American Medical Association 158: 103-106

Crasilneck H B, McCranie E J, Jenkins M T 1956 Special indications for hypnosis as a method of anesthesia. Journal of the American Medical Association 162: 1606-1608

Davenport-Slack B 1975 A comparative evaluation of obstetrical hypnosis and antenatal childbirth training. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 23: 266-281

Egbert L D, Battit G E, Welch C E, Bartlett M K 1964 Reduction of postoperative pain by encouragement and instruction of patients. New England Journal of Medicine 270: 825-827

Elton D, Burrows G D, Stanley G V 1980 Chronic pain and hypnosis. In: Burrows G D, Dennerstein L (eds) Handbook of hypnosis and psychosomatic medicine. Elsevier/North-Holland, Amsterdam, ch 15, p 269

Erickson J C III 1979 Hypnotic strategies in the daily practice of anesthesia. In: Burrows G D, Collison D R, Dennerstein L (eds) Hypnosis 1979. Elsevier/North-Holland, New York, p 195

Erickson M H 1967 An introduction to the study and application of hypnosis for pain control. In: Lassner J (ed) Hypnosis and psychosomatic medicine. Springer Verlag, New York, p 83

Esdaile J 1850 Hypnosis in medicine and surgery. The Julian Press, New York, reprinted 1957

Ewin D M 1979 Hypnosis in burn therapy. In: Burrows G D, Collison D R, Dennerstein L (eds) Hypnosis 1979. Elsevier/North-Holland, New York, p 269

Finer B 1980 Hypnosis and anesthesia. In: Burrows G D, Dennerstein L (eds) Handbook of hypnosis and psychosomatic medicine. Elsevier/North-Holland, Amsterdam, ch 16, p 293

Gardner G G 1976 Childhood, death, and human dignity: hypnotherapy for David. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 24: 122-139

Gardner G G 1981 Teaching self-hypnosis to children. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 29: 300-312

Gardner G G, Olness K 1981 Hypnotherapy for pain control. In: Hypnosis and hypnotherapy with children. Grune & Stratton, New York, ch 10, p 170

Gerschman J, Burrows G D, Reade P, Foenander G 1979 Hypnotizability and the treatment of dental phobic illness. In: Burrows G D, Collison

D R, Dennerstein L (eds) Hypnosis 1979. Elsevier/North-Holland, New York, p 33

Gottfredson D 1973 Hypnosis as an anesthetic in dentistry (dissertation). University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, Mich

Greene R J, Reyher J 1972 Pain tolerance in hypnotic analgesic and imagination states. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 79: 29-38

Hilgard E R 1980 Hypnosis in the treatment of pain. In: Burrows G D, Dennerstein L (eds) Handbook of hypnosis and psychosomatic medicine. Elsevier/North-Holland, Amsterdam, ch 14, p 233

Hilgard E R 1982 Hypnotic susceptibility and implications for measurement. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 30: 394-403

Hilgard E R, Hilgard J R 1975 Hypnosis in the relief of pain. William Kaufmann, Los Altos, Cal

Hilgard E R, Ruch J C, Lange A F, Lenox J R, Morgan A H, Sachs L B 1974 The psychophysics of cold pressor pain and its modification through hypnotic suggestion. American Journal of Psychology 87: 17-31

Hilgard E R, Morgan A H, Macdonald H 1975 Pain and dissociation in the cold pressor test: a study of hypnotic analgesia with ‘hidden reports’through automatic key-pressing and automatic talking. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 84: 280-289

Hilgard E R, Macdonald H, Morgan A H, Johnson L S 1978 The reality of hypnotic analgesia: a comparison of highly hypnotizables with simulators. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 87: 239-246

Hilgard J R, LeBaron S 1982 Relief of anxiety and pain in children and adolescents with cancer: quantitative measures and clinical observations. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 30: 417-442

Howard L, Reardon J P, Tosi D 1982 Modifying migraine headache through rational stage directed hypnotherapy: a cognitive-experiential perspective. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 30: 257-269

Johnson R F Q 1974 Suggestions for pain reduction and response to cold-induced pain. Psychological Record 24: 161-169

Knox V J, Morgan A H, Hilgard E R 1974 Pain and suffering in ischemia. Archives of General Psychiatry 30: 840-847

Knox V J, Gekoski W L, Shum K, McLaughlin D M 1981 Analgesia for experimentally induced pain: multiple sessions of acupuncture compared to hypnosis in high- and low-susceptible subjects. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 90: 28-34

Kroger W S 1977 Clinical and experimental hypnosis, 2nd edn. J B Lippincott, Philadelphia

Luthe W 1965 Autogenic training: correlationes psychosomaticae. Grune & Stratton, New York

McAmmond D M, Davidson P O, Kovitz D M 1971 A comparison of the effects of hypnosis and relaxation training on stress reactions in a dental situation. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 13: 233-242

McGlashan T H, Evans F J, Orne M T 1969 The nature of hypnotic analgesia and placebo response to experimental pain. Psychosomatic Medicine 31: 227-246

Margolis C G, De Clement F A 1980 Hypnosis in the treatment of burns. Burns 6: 253-254

Marmer M J 1963 Hypnosis in anesthesiology and surgery. In: Schneck J M (ed) Hypnosis in modern medicine. Charles C Thomas, Springfield, Ill

Melzack R, Perry C 1975 Self-regulation of pain: the use of alpha-feedback and hypnotic training for the control of chronic pain. Experimental Neurology 46: 452-469

Morgan A H, Hilgard E R 1973 Age differences in susceptibility to hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 21: 78-85

Morgan A H, Johnson D L, Hilgard E R 1974 The stability of hypnotic susceptibility: a longitudinal study. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 22: 249-257

Morse D R, Wilcko J M 1979 Nonsurgical endodontic therapy for a vital tooth with meditation-hypnosis as the sole anesthetic: a case report.

816 TEXTBOOK OF PAIN

American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 21: 258-262

Nasrallah H A, Holley T, Janowsky D S 1979 Opiate antagonism fails to reverse hypnotic-induced analgesia. Lancet i (8130): 1355

Orne M T 1980 On the construct of hypnosis: how its definition affects research and its clinical application. In: Burrows G D, Dennerstein L (eds) Handbook of hypnosis and psychosomatic medicine. Elsevier/North-Holland Amsterdam, ch 3, p 29

Orne M T 1983 Hypnotic methods for managing pain. In: Bonica J J et al (eds) Advances in pain research and therapy 5. Raven Press, New York, ch 85, p 847

Piccione C 1980 The effects of structured hypnotic imagery on the perception and reduction of ischemic pain by hypnotizable female students grouped as high and low imagers (dissertation). University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, Mich

Sacerdote P 1970 Theory and practice of pain control in malignancy and other protracted or recurring painful illnesses. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 18: 160-180

Sacerdote P 1980 Hypnosis and terminal illness. In: Burrows G D, Dennerstein L (eds) Handbook of hypnosis and psychosomatic medicine. Elsevier/North-Holland, Amsterdam, ch 22, p 421

Sacerdote P 1981 Teaching self-hypnosis to adults. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 29: 282-299

Schafer D W 1975 Hypnosis use on a burn unit. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 23: 1-14

Scott D L 1973 Hypnoanalgesia for major surgery--a psychodynamic process. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 16: 84-91

Scott D L 1974 Modern hospital hypnosis. Lloyd-Luke, London

Shot R E 1959 Explorations in hypnosis: a theoretical and experimental study. Dissertation, Brandeis University

Spanos N P, Horton C, Chaves J F 1975 The effects of two cognitive strategies on pain threshold. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 84: 677-681

Spanos N P, Radtke-Bodorik H L, Ferguson J D, Jones B 1979 The effects of hypnotic susceptibility, suggestions for analgesia, and the utilization of cognitive strategies on the reduction of pain. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 88: 282-292

Spiegel H, Spiegel D 1978 Trance and treatment: clinical uses of hypnosis. Basic Books, New York

Stern J A, Brown M, Ulett G A, Sletten 11977 A comparison of hypnosis, acupuncture, morphine, valium, aspirin, and placebo in the management of experimentally induced pain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 296: 175-193

Stone P, Burrows G D 1980 Hypnosis and obstetrics. In: Burrows G D, Dennerstein L (eds) Handbook of hypnosis and psychosomatic medicine. Elsevier/North-Holland, Amsterdam, ch 17, p 307

Thompson K F 1963 A rationale for suggestion in dentistry. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 5: 181-186

Tinterow M M 1960 The use of hypnotic anesthesia for major surgical procedures. American Surgeon 26: 732-737

Ulett G A, Parwatikar S D, Stern J A, Brown M 1978 Acupuncture, hypnosis and experimental pain. II. Study with patients. Acupuncture and Electro-Therapeutic Research International journal 3: 191-201

Vingoe F J 1968 The development of a group-alert trance scale. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 16: 120-132

Wadden T A, Anderton C H 1982 The clinical use of hypnosis. Psychological Bulletin 91: 215-243

Wakeman R J, Kaplan J Z 1978 An experimental study of hypnosis in painful burns. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 21: 3-12

Fig. 252 (p. 810) (from Hilgard, J.R., & LeBaron,

S. Relief of anxiety and pain in children and adolescents with cancer: Quantitative

measures and clinical observations. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental

Hypnosis, 1982, 30, 417-442. pg.430) is reproduced with the kind permission

of the Editor-in-Chief of The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental

Hypnosis and the surviving co-author Samuel LeBaron.