Shor, R. E., Orne, M. T., & O'Connell, D. N. Psychological correlates of plateau hypnotizability in a special volunteer sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1966, 3, 80-95.

Pennsylvania Hospital, The Institute, Philadelphia, and University of Pennsylvania

A number of specific hypotheses about correlates of hypnotizability were tested. A sample of 25 Ss representative of the investigators' special volunteer population was drawn. The criterion of hypnotizability used was the maximum hypnotic depth achieved in as many intensive hypnotic training sessions as E needed in order to feel confident that a stable plateau in the S's performance had been reached. Findings confirmed the hypotheses that hypnotizability could be predicted from a general propensity for unusual subjective hypnotic-like experiences, from attitudes and motivational factors specifically relating to hypnosis, and from postural sway, heat illusion, and vividness of mental imagery. In addition, with few exceptions the hypothesis was supported that there would be only negligible relationships between hypnotizability and measures of personality. Defining hypnotizability as a plateau performance rather than as some briefer estimate was shown to be cogent.

Over the years, in the process of training large numbers of volunteer subjects for participation in hypnosis research, the writers have developed clinical impressions or informal hypotheses about psychological indices which might predict hypnotizability. The present investigation was designed to test these impressionistic hypotheses. While in intent a hypothesis-testing experiment, the study has been developed in psychometric form. This procedure was used because the hypotheses under test refer to correlates of hypnotizability and because coefficients of correlation are often descriptively useful as rough guides for further evaluations.

In order to test the hypotheses appropriately it was felt essential to reproduce as accurately as possible the original conditions under which the impressions had been evolved. In methodological terms this requirement meant that two key features had to be included in the experimental design: the sample drawn had to be representative of the investigators' special population of volunteer subjects and the criterion of hypnotizability used in the study had to be equivalent to what the investigators have meant operationally by the term hypnotizability in their everyday usage.

IMPRESSIONIST HYPOTHESES

It has been the impression of the writers that hypnotizability is correlated with only two general types of psychological variables: with attributes bearing a close relationship to actual hypnotic performance, and with attitudes which are highly specific to hypnosis and to the hypnotic situation, such as attitudes toward entering hypnosis under the investigators' given laboratory conditions. Examples of attributes felt to be predictive are work samples taken in the waking state of mild hypnotic effects -- specifically in this regard, the Heat Illusion and Postural Sway tests. Another is the propensity for unusual subjective experiences as measured by life history reports of naturally occurring hypnotic-like experiences.

1 A condensation of this report was presented at the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, August 30, 1963, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The study was carried out while the writers were affiliated with Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts Mental Health Center. The work was supported in part by Contract AF 49 (638)-728 and Grant AF-AFOSR-88-66 from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

2 We wish to thank our co-workers, F. J. Evans, L. A. Gustafson, and Emily C. Orne for their helpful comments. Appreciation in this regard is also due to E. A. Cogen and U. Neisser. Statistical work was done in part at the Computation Center, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

80

81 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

Beyond these few indices it is the impression of the writers that hypnotizability does not correlate with any of the common dimensions of personality measurement such as hysteria, submissiveness, neuroticism, extraversion, social adjustment, impunitiveness, acquiescence tendency, intelligence, sex, and so forth. It is hypothesized that correlations sometimes reported between hypnotizability and these various types of measures are a function of inadequate criteria of hypnotizability, selective personal appeals of different hypnotists, and other situation-specific factors.

For example, a professor of psychology might consistently find a positive correlation between intelligence and hypnotizability in his research samples. This consistent correlation may occur, however, only because this particular investigator's prestige and personal manner selectively appeals more to his brighter subjects and tends to evoke greater resistance and hostility in his less bright subjects.

Another investigator might discover a correlation between neuroticism and hypnotizability but only because he expected to discover this correlation. Under the generic concept of demand characteristics Orne has shown that the hypnotist's expectations and the subjects' perceptions of these expectations will subtly alter all hypnotic behavior (Orne, 1959, 1962a, 1962b). Rosenthal's (1963) studies of outcome expectations of the experimenter have demonstrated the potency of these variables in several areas. It is plausible that the investigators' initial hypotheses are communicated to the subject and in association with situational influences elicit data confirming the investigators' predictions. For example, since the present investigators expected a correlation between propensity for naturally occurring hypnotic-like experiences and hypnotizability it is plausible that subtle cues in their behavior may unintentionally have contributed to the resulting correlation.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

The problem of determining correlates of hypnotizability first received serious theoretical attention during the celebrated Nancy-Salpetriere controversy of the 1880s. Charcot's (1882) neurological methodology led him mistakenly to believe that only persons constitutionally predisposed to hysteria could be hypnotized. To Charcot hypnotizability was associated with a specific pathological process. A much less restrictive viewpoint was adopted by Bernheim (1884). Marshaling the broad clinical experience of practitioners in the Nancy tradition Bernheim replied that all individuals had the capacity to manifest some degree of suggestibility under appropriate circumstances. To Bernheim hypnotizability was a normal and universal potentiality. Differences in responsiveness -- impressionability he called it -- were due to subtle resistances and varied habit patterns toward authority rather than to a lack of the underlying capacity to respond. The hypotheses advanced in this report are closely congruent with Bernheim's viewpoint.

In the early 1930s correlates of hypnotizability became a matter for empirical study rather than polemics as academic psychologists developed standardized scales for measuring hypnotic performance. The psychological testing movement was well developed and quantitative methods for expressing relationships were in general use.

Although seemingly promising at first, this line of psychometric inquiry after 35 years and over 50 studies is primarily a history of disappointments. Published findings are either initially negative or fail to be supported in further work. Because the findings have been conflicting, and because procedures of sampling and determinations of hypnotizability have been highly divergent and ambiguous, there appears no satisfactory method for drawing meaningful conclusions. It was against this background of empirical confusion that the investigators turned instead to their own impressions and laboratory conditions. For detailed reviews of the literature on correlates of hypnotizability see Barber (1964), Deckert and West (1963), and Weitzenhoffer (1953). The separate studies are discussed later in this report as relevant to the classification of tests used in this investigation.

82 CORRELATES OF HYPNOTIZABILITY

SAMPLING PROCEDURE

The selection procedure was designed to produce a sample representative of the investigators' special population of volunteer subjects. This special population is composed mostly of college student subjects who already have had considerable exposure to hypnotic training. About half of the individuals in this population are, moreover, at the two extreme ends of the continuum of hypnotic responsiveness -- that is, the distribution is rectangular rather than Gaussian. This abnormal distribution is produced because the majority of experiments on hypnosis in the laboratory require the use both of many highly responsive and unresponsive subjects. In other words, in the process of continually developing the volunteer subjects pool the investigators had strongly tended to expend their primary effort in locating as many individuals as possible at the two extremes of hypnotic responsiveness.

Subjects

The sample was composed of 25 students from universities in the Boston area. The subjects were individuals interested in hypnotic experimentation, willing to participate in a lengthy series of psychological testing with only token monetary payment. The subjects were obtained on a random basis from the available pool. In the years prior to the experiment, many hundreds of subjects had passed through the laboratory with variable amounts of hypnotic training and experimental participation. Thus, most of the individuals selected for inclusion in this study had already received extensive hypnotic training prior to the experiment; as a result some subjects were able to enter deep hypnosis early while others were unresponsive to hypnosis in repeated hypnotic training sessions. Only 6 of the 25 subjects selected had had no prior exposure to hypnotic training. The inclusion of these few inexperienced subjects in the sample was intended to reflect the fact that at the time of the study about a fourth of the laboratory's training sessions were devoted to initial hypnotic screenings.

THE CRITERION OF HYPNOTIZABILITY

The criterion of hypnotizability used in this study was equivalent to what the investigators have meant operationally by the term hypnotizability in their everyday usage. In most studies hypnotizability has been defined in terms of a single score on a limited test of hypnotic performance. The assumption made is that relative ratings of the subjects' performance would not be greatly altered by additional hypnotic training. In the present study, however, a subject's hypnotizability was defined as the maximum hypnotic depth achieved in as many intensive hypnotic training sessions as the experimenter needed in order to feel confident that a stable plateau in the subject's hypnotic performance had been reached. The controversy regarding "universal" hypnotizability remains unresolved; that is, whether or not with unlimited time and ingenuity everyone eventually could be profoundly hypnotized. Nevertheless all empirical workers agree that if apparently cooperative subjects are given skillful and intensive training, that most subjects most of the time rapidly reach a plateau in hypnotic performance after which no appreciable improvement occurs regardless of the hypnotist, the methods used, or the amount of further training.

Defining a subject's hypnotizability as his stable plateau in hypnotic performance means that two diagnostic estimates are necessary: a performance rating is needed of the actual maximum hypnotic depth which the subject achieves in a given session, and a judgment is needed indicating that the subject's hypnotic performance would be very unlikely to improve with additional training.

Procedure

In these hypnotic training sessions the examiner was allowed freedom to utilize any techniques which seemed appropriate and to explore clinically any issues which might then help maximize performance. All hypnotic sessions were administered by one of the investigators (MTO). To secure estimates of interjudge reliability another of the investigators (RES) observed all of the sessions through a one-way mirror with audio arrangements.

Both the experimenter and the observer independently rated the maximum depth achieved. These ratings were clinical diagnoses by experienced hypnotists based upon both objective hypnotic behavior and the subjects' report. For each of the subjects the experimenter eventually made the judgment that further improvement in hypnotic performance was highly unlikely. Performances in these final training sessions were classified into four categories: less than light, light, medium, and deep. For all inferential purposes these four categories are consistent with the understandings of these terms in common usage

83 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

and descriptively correspond to the major divisions of the Davis-Husband scale (Davis & Husband, 1931). The two sets of final performance ratings were almost identical (r = .96) with virtually no mean difference. They were averaged to form a single criterion measure of hypnotizability.

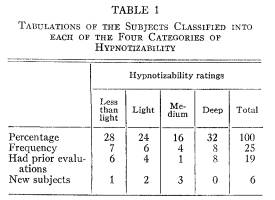

Tabulations of the subjects classified into each of the four categories of hypnotizability are presented in Table 1. An approximately equal percentage of subjects fell into each of the four categories so that the distribution is roughly rectangular. This distribution is not characteristic of the general population but rather represents the special sampling procedures of our laboratory.

SPECIFIC PREDICTIONS

The psychological tests included in the present investigation are classified below into five groups. The hypotheses tested are presented as specific predictions. The tests are described in more detail in the section on Description of Tests.

I. Proneness for unusual subjective hypnotic-like experiences. This group refers to the subjects' propensity to experience hypnotic-like experiences where external reality is not the major determinant of subjective reality. This concept was measured by a set of Personal Experiences Questionnaires. It was predicted that these tests would correlate positively with the criterion of hypnotizability.

II. Attitudes and motivational factors specifically relating to hypnosis. This group refers to factors arising from the subjects' attitudes and motives, persistent but potentially modifiable, which specifically relate to being hypnotized -- that is, conscious and nonconscious attitudes toward hypnosis, preconceptions, fears, motives, situational and interpersonal considerations directly relevant to entering hypnosis under the given conditions. These concepts were measured by three tests: Card 12M of the Thematic Apperception Test (Murray, 1943), Traits Regarding Hypnosis Inventory, and Background Index on Hypnosis. It was predicted that these tests would correlate positively with the criterion of hypnotizability.

III. Personality attributes. This group refers to common paper-and-pencil measures of stable and enduring personality attributes -- for example, measures of hysteria, submissiveness, neuroticism, extraversion, social adjustment, impunitiveness, etc. These concepts were measured by five tests: Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI; Hathaway & McKinley, 1951), Minnesota Personality Scale (MPS; Darley & McNamara, 1941), Rosenzweig (1938) PictureFrustration (P-F) Study, Puzzles "Repression" Test (Rosenzweig & Sarason, 1942), and Acquiescence Tendency (Couch & Keniston, 1960). It was predicted that these tests would not appreciably correlate with the criterion of hypnotizability.

IV. Subsidiary criteria of hypnotic performance. This group refers to measures of hypnotic performance other than the specific criterion of hypnotizability used in this investigation. These measures were secured by two tests. Subjective Estimates of Percentage Depth and the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (SHSS), Forms A and B (Weitzenhoffer & Hilgard, 1959). It was predicted that these tests would correlate positively with the criterion of hypnotizability, but they were not intended to be considered as independent predictor variables.

V. Miscellaneous. This group includes a number of tests: Postural Sway Test (Eysenck & Furneaux, 1945), Heat Illusion Test (Eysenck & Furneaux, 1945), Vividness of Mental Imagery Questionnaire, and the Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale, Form II (Wechsler, 1946). In addition, the subjects' sex also was used as a variable. It was predicted that postural sway, heat illusion, and mental imagery would correlate positively with the criterion of hypnotizability, but that intelligence and sex would not correlate.

84 CORRELATES OF HYPNOTIZABILITY

ORDER OF TEST ADMINISTRATION

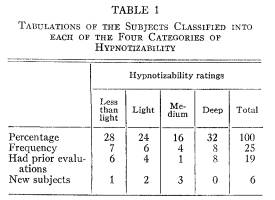

Order of test administration is presented in Table 2. A few of the tests were repeated twice. Subjects were run individually through the sequence of testing in 3 days to 2 months, as their schedules permitted. The average was about 3 weeks. The time required for the subjects to complete the testing varied between 12-20 hours. The average was about 16 hours.

Description of Tests

The tests included in the study are described below. 3

Propensity for unusual subjective hypnotic-like experiences. Personal Experiences Questionnaires: A relationship has been demonstrated between hypnotic performance and life-history reports on naturally occurring hypnotic-like experiences (Shor, 1960; Shor, Orne, & O'Connell, 1962). A number of investigators have incorporated these materials into their own prediction studies. With one exception (Barber & Calverley, 1965) results have been favorable (As & Lauer, 1962; As, O'Hara, & Munger, 1962; Evans & Thorn, 1964; London, Cooper, & Johnson, 1962; Thorn, 1960).4

Three varieties of Personal Experiences Questionnaires were used in the present study.

1. Personal Experiences Questionnaire-Long Form (PEQ-L) : A 149-item paper-and-pencil self-report questionnaire was developed to elicit reports on a wide variety of hypnotic-like experiences occurring naturally in the normal course of living, independent of the use of special techniques, such as hypnosis, sensory-deprivation, drugs, etc. Two scoring systems were used: frequency -- how often the subjects have had the experience described, and intensity -- how vivid and profound was a subject's single most intense experience of it. Relevant quantitative scales were provided. (Also discussed in Shor et al., 1962.)

2. Imaginary playmates: At the end of the PEQ-L were appended a number of questions inquiring about the existence and apparent reality of imaginary playmates during childhood. These questions were scored as a separate unit.

3. Personal Experiences Questionnaire-Short Form: In a prior publication normative data were presented on 44 items selected from the PEQ-L (Shor, 1960). The scoring system was based on simple occurrence, that is, subjects replied only on whether they had ever had the experiences described.

Attitudes and motivational factors specifically relating to hypnosis. Card 12M of the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) : Four cards were selected from the TAT and administered with the standard modification for written responses.

In order of administration, the four cards were: boy with violin, 1; two men standing, 7BM; man and reclining figure, 12M; and men reclining, 9BM. The third card in this set, 12M, has often been interpreted as depicting hypnosis, and it was taken as the "hypnosis" card which White (1937a) and later Sarason and Rosenzweig (1942) found elicited attitudes toward hypnosis which correlated with hypnotizability. 5 A number of other investigators have also used Card 12M in their hypnosis research (Levitt, Lubin, & Brady, 1962; Levitt, Lubin, & Zuckerman, 1959; Schneck, 1951; Secter, 1961b; Ventur, Kransdorff, & Kline, 1956).

Transcripts of the Card 12M protocols were coded and randomized. Four judges independently rated the protocols for estimates of hypnotizability, without instruction or restrictions as to the criteria of judgment to be applied. 6

Traits Regarding Hypnosis Inventory: A paperand-pencil inventory was designed to elicit attitudes

3 Specimen forms and scoring instructions of new tests have been deposited with the American Documentation Institute. Order Document No. 8607 from ADI Auxiliary Publications Project, Photoduplication Service, Library of Congress, Washington, D. C. 20540. Remit in advance $3.00 for microfilm or $8.75 for photocopies and make checks payable to: Chief, Photoduplication Service, Library of Congress.

4 This natural occurrence approach has parallels in earlier studies. See Barry, MacKinnon, and Murray (1931), Sutcliffe (1958), White (1937b), and Williams (1952).

5 It was discovered too late that the original "hypnosis" card was not Card 12M. The original drawing, lost sight of during the early years of the TAT's standardization, was very similar in scenic content to the present Card 12M, but it had more hypnotic quality. A copy of the original card has since been secured from H. A. Murray.

6 Two other scoring methods had been planned: the criteria which White's judges appeared to have used and Sarason and Rosenzweig's system. Both methods proved inapplicable to the present Card 12M data.

85 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

toward hypnosis by means of a brief adjective check list. The objective was to develop a device yielding information comparable in principle with White's use of the "hypnosis" TAT card. The inventory was designed to preserve some of the features of a projective device but with objective scoring. The inventory had two parts. The first inquired about traits presumed to characterize a good hypnotic subject; the second inquired about traits presumed to characterize a good hypnotist. Scoring was the sum of favorable, plus not unfavorable responses.

Background Index on Hypnosis: A paper-and-pencil questionnaire was designed to inquire about the subjects' knowledge, attitudes, and impressions about hypnosis. The questionnaire was composed of a number of separate sections.7

1. Impressions of Percentage Pleasantness: Subjects were first required to describe their prior experiences as hypnotic subjects, their observations and reading about hypnosis, etc. They were then asked to estimate from all of their sources of factual information what percentage of the time the typical subject in hypnosis seemed to be enjoying himself and what percentage of the time hypnosis seemed unpleasant to him.

2. Circumstances of Agreeing to Participate in Hypnosis: Subjects were asked to describe the circumstances under which they would volunteer to participate in hypnosis. Seven specific situations were cited covering a wide range of circumstances; for example, medical research, a fraternity party, etc. Scoring was based on the sum of agreements to participate.

3. The Effects of Conditions on Initial Induction: A check list was provided in which subjects were asked to classify a series of 73 items in terms of how they felt specific circumstances would effect initial hypnotic induction. Typical items were "being comfortable," "a close friend of your choice watching," "just having failed an examination," etc. A 5-point scale was provided: (a) necessary to induce hypnosis, (b) favorable in inducing hypnosis, (c) neutral or uncertain, (d) unfavorable in inducing hypnosis, and (e) prevents hypnosis. Scoring was based on the number of extreme responses (summation a + e).

4. Conceptions of Hypnotic Depth: A 30-item check list was provided for subjects to classify their impressions of the depth of hypnosis required to first produce a series of described phenomena. Typical items were: "the inability to open the eyelids when challenged to do so," "the feeling of not wanting to resist the hypnotist's suggestions," "feeling as if your body were drifting through space," and so forth. Eight of the items were grossly farfetched; for example, "the ability to accurately predict the future by going forward in time." A 5-point scale was provided: (a) waking state, (b) light hypnosis, (c) medium hypnosis, (d) deep hypnosis, and (e) does not happen.

A scoring stencil was designed to yield three separate scores which may be briefly characterized as follows: extent of "magical" notions, extent of "skepticism," and extent of agreement with the opinions of recognized authorities on hypnosis.

Personality attributes. The MMPI and the MPS: The MMPI is a paper-and-pencil self-report personality inventory of 550 items providing measures of nine basic psychiatric scales as well as many derived scales. The MPS is a paper-and-pencil self-report personality inventory of 218 items providing five measures of individual and social adjustment. Unlike the MMPI, originally standardized to diagnose common psychiatric classifications, the MPS has been standardized to be applicable to the features of personality adjustment most relevant to the general college population.

Although it was not feasible to include every personality inventory related to hypnotizability by one or another investigator, it was believed that the MMPI and the MPS together would be representative of most measures available through this type of paper-and-pencil instrument. 8

Rosenzweig P-F Study and Puzzles "Repression" Test: In 1938 Rosenzweig hypothesized that hypnotizability was positively associated with repression as a preferred mechanism of defense and with impunitiveness as a characteristic type of immediate reaction to frustration. Evidence for this hypothesis was later reported (Rosenzweig & Sarason, 1942), in which impunitiveness was measured with the Rosenzweig P-F Study (a paper-and-pencil inventory) and repression was measured by amount of negative Zeigarnik effect under anxiety-provoking circumstances. In the repression test a set of 6-8 piece jigsaw puzzles was administered under the guise of an intelligence test in such a way that the subjects could successfully complete only half of the puzzles .9 A

7 For related approaches on measuring attitudes see Brightbill and Zamansky (1963), London et al. (1962), Melei and Hilgard (1964), and Rosenhan and Tomkins (1964).

8 See in this regard Barber (1956) ; Barber and Calverley (1964, in press) ; Barry et al. (1931) ; Cooper and Dana (1964) ; Das (1964) ; Faw and Wilcox (1958) ; Friedlander and Sarbin (1938) ; Hilgard and Lauer (1962); Lang and Lazovik (1962); Levitt, Brady, and Lubin (1963) ; Messer, Hinckley, and Mosier (1938) ; Moore (1961) ; Sarbin (1950) ; Schulman and London (1963) ; Secter (1961a); Thorn (1960) ; Weitzenhoffer and Weitzenhoffer (1958) ; White (1930) ; White (1937b, 1941) ; Wilcox and Faw (1959). A number of investigators have related Rorschach test personality variables to hypnotizability: Bergmann, Graham, and Levitt (1947) ; Brenman and Reichard (1943) ; Levine, Grassi, and Gerson (1943); Sarbin (1939); Sarbin and Madow (1942) ; and Schafer (1947).

9 An intensive search failed to locate Rosenzweig and Sarason's original set of puzzles. New materials were thus compiled and carefully pretested. Care was taken to preserve and enhance the features of the test which Rosenzweig and Sarason had considered important, such as making the test appear to be a commercially available intelligence test.

86 CORRELATES OF HYPNOTIZABILITY

greater percentage of recall of successfully completed items was taken as the index of repression. The repression study has been replicated, however, with null findings. (See Eysenck, 1947; Petrie, 1948. On Impunitiveness, see Willey, 1951.)

Impunitiveness and repression scores were computed by the methods described by Rosenzweig and Sarason. Because it seemed that the computation of the impunitiveness score had a considerable nonobjective component, all protocols were coded and scored blindly by three judges. Average interrater reliability was .78. The scores of the judges were then averaged.

Acquiescence Tendency: Agreeing Response Set has been defined as the general tendency to agree with psychological test items regardless of their content. A number of investigators have hypothesized that this general tendency is a manifestation of a relatively stable personality characteristic to acquiesce to authority (Couch & Keniston, 1960). Theorists often have supposed that highly hypnotizable individuals possess this attribute. Two measures of acquiescence tendency (agreeing response set) were included in this study: Over-all Agreement Score (OAS; Couch & Keniston, 1960), and the summation of responses marked true on the MMPI.

Subsidiary criteria of hypnotic performance. Subjective Estimates of Percentage Depth: During an interview conducted by one of the investigators (RES) at the end of the battery of testing, subjects were asked to estimate how deeply they had been hypnotized in the hypnotic training sessions in terms of their own, unaided understandings of the deepest hypnosis. A specific, percentage rating scale was provided, a variant of procedures used by earlier investigators who had reported on subjective estimates of depth (Barry et al., 1931; Hatfield, 1961; Israeli, 1953; LeCron, 1953; White, 1930).

SHSS: The SHSS was administered twice to each subject by one of the investigators (DNO'C). Form A of the scale was always administered first, before the hypnotic training and evaluation sessions; Form B was always administered second, after the training sessions.

Miscellaneous. Postural Sway Test and Heat Illusion Test: Eysenck (1947), Eysenck and Furneaux (1945), and Furneaux (1946, 1956), using hospital patient populations, reported multiple correlations between hypnotizability and the Postural Sway Test and the Heat Illusion Test of .96 and .92. The correlation between hypnotizability and the Postural Sway Test alone was reported as .73 and .64. The correlation between hypnotizability and the Heat Illusion Test alone, was reported as .51 and .59.

The Postural Sway Test, standardized by Hull (1933), measures the amount of bodily sway in response to so-called waking suggestions during a specified time period.

The Heat Illusion Test was described as early as 1893 by Scripture. The subject is asked to hold an electrical resistor which is slowly heated as he turns a calibrated knob. The subject is then asked to report when he first begins to feel heat. The indicator is then turned back to 0, and the procedure repeated. The second time, however, the current has been secretly turned off.

The procedures for administering and scoring these two tests as described by Eysenck were replicated closely. Eysenck's original recording of swaying suggestions was secured from Star Sound Recording Studios, Cavendish Square, London, and used throughout. Wording of other procedures was kept identical. The only known modification was that a silent time-delay hidden switch was built into the Heat Illusion apparatus rather than a manual hidden switch.

The Heat Illusion Test was concealed among a series of five other "Perceptual and Physiological Tests," which were not scored. The Postural Sway Test was administered at the end of the series.

It had been the informal experience of the investigators that the Postural Sway Test and other similar measures discriminated moderately well between those subjects who later respond positively to at least the easiest hypnotic suggestions and those subjects who later showed even fewer or no hypnotic responses at all. The investigators had never found such tests more than weak predictors, however, of ultimate hypnotic performance. Similarly, our impression was that the Heat Illusion Test had only a slight to moderate predictive value. Thus, it was predicted that the Postural Sway and Heat Illusion tests would correlate with hypnotizability, but that the multiple prediction would not be very high.

Vividness of Mental Imagery Questionnaire: A paper-and-pencil questionnaire of 15 items was designed to inquire about the vividness of the mental{ imagery which the subjects report having generally available in the usual waking state. Subjects were asked to rate on a 7-point scale the clarity and vividness of their waking imagery in various sensory modalities. The questionnaire was a variation of Betts' (1909) Imagery Questionnaire, which Sutcliffe (1958) had found differentiated his somnambules from nonsomnambules. McBain (1954) also had found a relationship between imagery and hypotizability. The new questionnaire was evolved to provide simpler items, more in keeping with the type of imagined experiences often required of hypnotic subjects.

It was predicted that vividness of imagery would correlate with hypnotizability, but it was felt that the

87 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

correlation might be artifactual. Shor (1962) has theorized that individuals with more vivid waking imagery have an uncontrolled advantage in the performance of those hypnotic phenomena involving imagery, particularly in hallucinations. The crux of hypnotic fantasy, in Shor's theoretical view, is not the vividness of the mental imagery as such but rather how completely the subjects believe in the reality of the hypnotic fantasy at the moment of the experience. The view is that even relatively shoddy imagery may appear phenomenally real to the subject at the moment of the experience provided his usual waking standards of comparisons have sufficiently faded.

Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale, Form II: The Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale, Form II, was individually administered to the subjects by a trained research assistant. A number of investigators have reported positive correlations of intelligence with hypnotizability (Barry et al., 1931; Curtis, 1943; Davis & Husband, 1931; Friedlander & Sarbin, 1938; Hull, 1933; White, 1930).

Sex: Sex differences in hypnotizability favoring females have occasionally been reported (Davis & Husband, 1931; Friedlander & Sarbin, 1938; Hilgard, Weitzenhoffer, & Gough, 1958; London et al., 1962).

RESULTS

Correlations are reported for each predictor variable against the criterion of hypotizability. As pertinent, other correlations are also presented. Since directions of relationship often were predicted it seemed valuable also to report the .10 level. 10

Propensity for Unusual Subjective Hypnotic-like Experiences

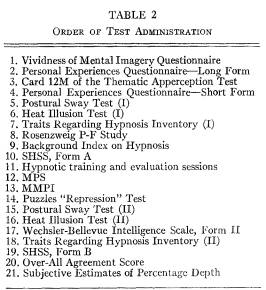

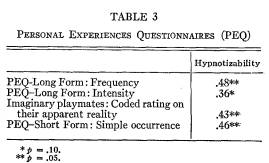

Personal Experiences Questionnaires. Correlations between hypnotizability and the personal experiences measures are presented in Table 3. Response consistency and internal consistency reliabilities of the Personal Experiences Questionnaires have already been reported as very high (.90 to .96, p = .01, in Shor, 1960, and Shor et al., 1962).11

Attitudes and Motivational Factors Specifically Relating to Hypnosis

Card 12M of the TAT. Correlations between hypnotizability and the four judges' blind ratings were .23; .68, p = .01; .13 and .44, p = .05. The correlation with the summation ranks of the judges' ratings was .58, p = .01.

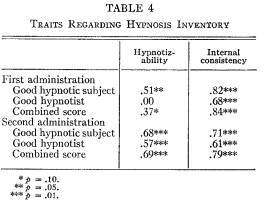

Traits Regarding Hypnosis Inventory. Correlations between hypnotizability and the two administrations of the inventory and internal consistency reliabilities (split-halves, Spearman-Brown) are presented in Table 4.

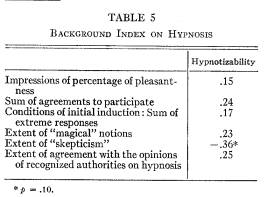

Background Index on Hypnosis. Correlations between hypnotizability and the index are presented in Table 5. Only one of the six comparisons achieved significance .12

10 In a very few instances of missing data statistical significance was determined on the reduced sample size.

11 In addition, London et al. (1962) found test-retest reliability of the PEQ-Short Form over a 3-week interval to be .94, p = .01. As' Experiences Inventory incorporated the instructions plus 18 items from the PEQ-Short Form along with 42 items devised independently; very high stability in answer percentages across samples were demonstrated for the common items (As et al., 1962).

12 It became apparent even before the data were fully gathered that the background index had a serious defect in test construction. The approach used was to elicit attitudes toward hypnosis by phrasing questions in the factual format of college examinations. The subjects' replies, however, so strongly tended to reflect the enlightened skepticism of the

88 CORRELATES OF HYPNOTIZABILITY

Personality Attributes

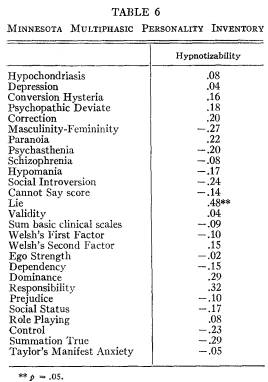

MMPI. Correlations with hypnotizability are presented in Table 6. Out of 27 basic and derivative scales only the correlation with the Lie scale was statistically significant. Except for Responsibility, none other had a coefficient larger than .30. By any standards of multiple probabilities findings in the table were null. 13

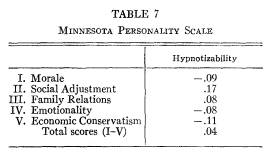

MPS. Correlations with hypnotizability are presented in Table 7; all were negligible.

Rosenzweig P-F Study and Puzzles "Repression" Test. The correlations between hypnotizability and the two triadic hypothesis variables were negligible (with impunitiveness, .27; with "repression," -.18). The correlation of the two predictors was .20.

Acquiescence Tendency. Correlations between hypnotizability and the two measures of acquiescence tendency (agreeing response set) were both -.27. The correlation between the two acquiescence measures was .62, p = .01.

Subsidiary Criteria of Hypnotic Performance

Subjective Estimates of Percentage Depth. The correlation between hypnotizability and the percentage estimates was .74, p = .01.

SHSS. The correlation between hypnotizability and Form A of the SHSS was .75, p = .01; the correlation with Form B was .93, p = .01. This increase is statistically significant (p < .005). It will be recalled that Form A was administered before the hypnotic training sessions; Form B was administered after their completion. When administered under comparable conditions, Forms A and B have been shown to be normative equivalents (Hilgard, Weitzenhoffer, Landes, & Moore, 1961; Weitzenhoffer & Hilgard, 1959).

Miscellaneous

Postural Sway Test and Heat Illusion Test. The correlations between hypnotizability and the two administrations of the Postural Sway Test were .32 and .37, respectively, p = .10; were .36, p = 10, and .02, for the Heat Illusion Test; and were .47, p = .05, and .38, p = .10, for the multiple predictors. Intercorrelations of the two predictors were .03 for the first administration and -.08 for the second administration. The test-retest reliability of the Postural Sway Test was .84, p

Footnote 12 cont. college students' subculture that personal attitudes seemed neglected. See London (1961) for a similar observation.

13 Furneaux and Gibson (1961) and Das (1964) have reported negative correlations between hypnotizability and the Lie scale of the Maudsley Personality Inventory. The measurement operations of the two scales are not similar, however. For other investigations on hypnotizability with the Maudsley Personality Inventory see Cooper and Dana (1964), Evans (1963), Furneaux (1961), Hilgard and Bentler (1963), Lang and Lazovik (1962), and Thorn (1960).

89 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

= .01, of the Heat Illusion Test, .58, p = .01. 14

Vividness of Mental Imagery Questionnaire (VMI). The correlation between hypnotizability and the VMI was .56, p = .01. Internal consistency reliability (odd-even, Spearman-Brown) for the VMI was .91, p = .01, for the first administration and .93, p = .01, for the second.

Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale, Form II. The correlation between hypnotizability and intelligence was -.50, p = .05.

Sex. The correlation (point biserial) between hypnotizability and sex was .46, p = .05, with females the more hypnotizable.

SUMMARY OF RESULTS ON HYPOTHESES

A general summary is given in Table 8 comparing results with the initial hypotheses under test. Tests are arranged and classified in rows. The predicted and actually observed directions of relationships are noted in the second and third columns of the table. Observed strengths of the relationships are described verbally in the fourth column. 15 Indicated in the final column is whether the findings tend to confirm or reject the initial hypotheses.

Most of the hypotheses were supported. The Background Index was the only unsuccessful prediction of a positive relationship. Regarding predictions of negligible relationships, two unexpected significant correlations with hypnotizability were discovered, intelligence and sex. 16 It should be noted that contrary to previous findings, the observed relationship between intelligence and hypnotizability was negative in direction.

Except for the Subsidiary Criteria of Hypnotic Performance (which were not distinct predictor variables) positive correlations

14 Minor alterations in procedure may improve the Heat Illusion Test's reliability and consequently its predictive power (Furneaux, 1964).

15 These descriptions are based on the convention of general verbal nomenclature for correlations suggested by Guilford (1956, p. 145): .00-.20 slight,.20-.40 low, .40-.70 moderate, .70-.90 high, .90-1.00 very high. Insignificant correlations are considered negligible.

16 It could be argued that a third unexpected significant correlation was found for the Lie scale of the MMPI.

90 CORRELATES OF HYPNOTIZABILITY

with hypnotizability had been predicted for seven types of test. These seven were: Personal Experiences Questionnaires, Card 12M of the TAT, Traits Regarding Hypnosis Inventory, Background Index on Hypnosis, Postural Sway Test, Heat Illusion Test, and Vividness of Mental Imagery Questionnaire.

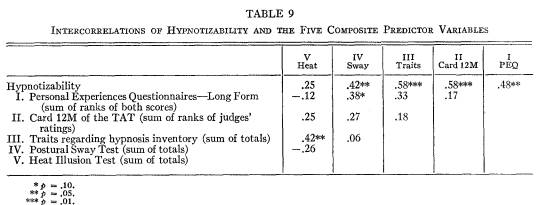

To provide a convenient summary index, a multiple correlation has been computed between hypnotizability and five of these

91 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

seven. 17 The matrix is presented in Table 9. For stable scores, composites were used, as indicated in the table. The hypnotizability criterion had already previously been computed as a composite of both examiner's and observer's final performance ratings. The multiple correlation is .77, p = .01. 18

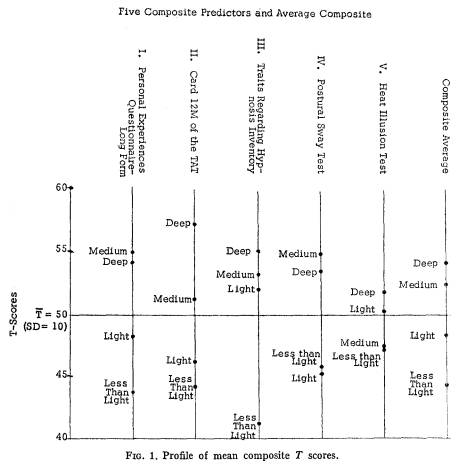

By transforming all composite scores into the same unitage (Anderson & Barnhart, 1959), a profile chart has been constructed to describe these relationships further. Mean composite T scores are presented in Figure 1 for each of the four categories of hypnotizability. Averages of T score means are also presented. There are only a few minor inconsistencies between hypnotizability and the relative magnitudes of the T score means. These inconsistencies are eliminated in the final averages.

DISCUSSION

The hypotheses tested were generally supported as evidenced by the significance level of the separate correlations and the summary of results. Findings confirmed that hypnotizability could be predicted from a general propensity for unusual subjective hypnoticlike experiences, from attitudes and motivational factors specifically relating to hypnosis, and from postural sway, heat illusion, and vividness of mental imagery. In addition, the hypothesis was supported that there would be only negligible relationships between hypnotizability and the measures of personality usually employed. It is concluded that the investigators' impressions about correlates of hypnotizability were generally confirmed with the two exceptions of intelligence and sex.

It should be emphasized that the magnitudes of the reported correlations must be interpreted in the light of the special population sampled and the small sample size. The study was conceived to test specific hypotheses about correlations between hypnotizability and other parameters in a salient population. Because the hypotheses being tested refer to correlates of hypnotizability and because coefficients of correlation are often descriptively useful as rough guides in further evaluations, the study was carried out in correlational form. It would be misleading, however, to take the results at face value in simple correlational terms as if the results were generalizable directly to a broader population. The extent to which the correlations reported here will hold up in other populations remains to be established in future work. The special population sampled overrepresents the extremes of hypnotic responsiveness as compared with the general population. While salient to the hypotheses under test, such a sample might be expected to show higher correlations than samples drawn from broader populations. Moreover, as the sample size is small it should be borne in mind that relatively few cases may be responsible for a given finding.

One of the major differences between this study and others reported in the literature is the care with which plateau hypnotizability was evaluated. This is a time-consuming procedure and was largely responsible for the limited sample size. However, we feel it is indispensible for some purposes. A simple and brief procedure for estimating hypnotic depth such as the SHSS was found to reflect the hypnotizability criterion after subjects had been trained to plateau hypnotic performance quite accurately (.93), but the SHSS yielded only a correlation of .75 with the hypnotizability criterion when administered prior to the achievement of plateau, and even this correlation is probably spuriously high due to the fact that most of the subjects already had had a great deal of exposure to hypnotic training prior to entering the study. Thus, while measures such as the SHSS are very useful and may accurately reflect hypnotizability after training, it is dubious whether

17 The Background Index on Hypnosis was excluded from this comparison because it was unsuccessful. The successful Vividness of Mental Imagery Questionnaire was excluded because the investigators had suspected that the relationship might be artifactual.

18 The multiple correlation was computed stepwise, entering the five compositors in order of their predictiveness. As noted, the best predictor, the Traits Inventory, correlated .58 with criterion. Adding Card 12M TAT to the predictor yielded a multiple correlation of .70. Entering the PEQ further inflated the value to .77. The remaining two predictors, Postural Sway and Heat Illusion, raised the coefficient only in the third decimal place.

92 CORRELATES OF HYPNOTIZABILITY

reliance should be placed on such brief estimates without extensive hypnotic training to plateau hypnotizability if one is attempting to assess correlates of established hypnotizability rather than of just initial hypnotic performance.

The general confirmation of our predictions under the specified conditions is, however, only a first step into elucidating the functional dependencies underlying the observed correlations. As was noted earlier, we were concerned with the extent to which the resulting correlations were a function of hypnotizability as a trait as opposed to the extent to which they were determined by the demand characteristics of the experimental situation. We wondered whether our own initial hypotheses and the subjects' perception of these hypotheses might not have set into motion interacting expectancies and other situational inferences, subtly altering the pattern of correlations in the direction of confirming the initial predictions. To what extent did postural sway predict hypnotizability in the study because of an inherent, intrinsic relationship or to what extent did postural sway predict hypnotizability because both the experimenter and the subjects shared the belief that it would predict it?

It should be emphasized that attitude measures were taken after most of the subjects had had considerable exposure to hypnotic training. It has been noted in some studies (e.g., Melei & Hilgard, 1964) that attitudes may be influenced by successful or unsuccessful hypnotic experience.

The hypothesis that demand characteristics, experimenter bias, order effects, and situational factors may confound the observation of reliable correlates of hypnotizability provides a useful context for future empirical work and may help explain the conflicting results of earlier studies. Certainly the relative lack of success noted in the literature in identifying reliable correlates of hypnotizability is in striking contrast to the relative ease with which hypnotic performance may be assessed using a work sample. Eventually we may learn to identify and isolate the confounding factors by studying how correlates of hypnotizability are affected or remain invarient under differing experimental conditions. In the present study the investigators' hypotheses were tested under conditions closely resembling those in which they were derived by the investigators. We have been careful to specify the conditions and the hypotheses. Further studies will attempt to evaluate the extent to which these hypotheses hold under other conditions and with differing sets of expectancies by both experimenter and subjects.

REFERENCES

ANDERSON, K. E., & BARNHART, E. L. Tables for transmutation of orders of merit into normal equivalents. Journal of Experimental Education, 1959, 27, 177-186.

AS, A., & LAUER, LILLIAN W. A factor-analytic study of hypnotizability and related personal experiences. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1962, 10, 169-181.

AS, A., O'HARA, J. W., & MUNGER, M. P. The measurement of subjective experiences presumably related to hypnotic susceptibility. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 1962, 3, 47-64.

BARBER, T. X. A note on "hypnotizability" and personality traits. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1956, 4, 109-114.

BARBER, T. X. Hypnotizability, suggestibility, and personality: V. A critical review of research findings. Psychological Reports, 1964, 14(1), 299-320.

BARBER, T. X., & CALVERLEY, D. S. Hypnotizability, suggestibility, and personality: I. Two studies with the Edwards Personal Preference Schedule, the Jourard Self-Disclosure Scale, and the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. Journal of Psychology, 1964, 58, 215-222.

BARBER, T. X., & CALVERLEY, D. S. Hypnotizability, suggestibility, and personality: II. Assessment of previous imaginative-fantasy experiences by the As, Barber-Glass, and Shor questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 1965, 21, 57-58.

BARBER, T. X., & CALVERLEY, D. S. Hypnotizability, suggestibility, and personality: IV. A study with the Leary Interpersonal Checklist. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, in press.

BARRY, H., MacKINNON, D. W., & MURRAY, H. A., Jr. Studies in personality: A. Hypnotizability as a personality trait and its typological relations. Human Biology, 1931, 3, 1-36.

BERGMANN, M. S., GRAHAM, H., & LEAVITT, H. C. Rorschach exploration of consecutive hypnotic chronological age level regressions. Psychosomatic Medicine, 1947, 9, 20-28.

BERNHEIM, H. M. De la suggestion dans l'etat hypnotique et dens l'etat de veille. Paris: Libraire scientifique et philosophique, 1884.

BETTS, G. H. The distribution of and function of mental imagery. Teachers College, Contributions to Education, 1909, No. 26.

93 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

BRENMAN, MARGARET, & REICHARD, SUZANNE. Use of the Rorschach test in the prediction of hypnotizability. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 1943, 7, 183-187.

BRIGHTBILL, R., & ZAMANSKY, H. S. The conceptual space of good and poor hypnotic subjects: A preliminary exploration. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1963, 11, 112-121.

CHARCOT, J. M. Essai d'une distinction nosographique des divers etats compris sous le nom d'Hypnotisme. Comtes rendus de l'Academie des Sciences, 1882, 44.

COOPER, G. W., Jr., & DANA, R. H. Hypnotizability and the Maudsley Personality Inventory. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1964, 12, 28-33.

COUCH, A., & KENISTON, K. Yeasayers and naysayers: Agreeing response set as a personality variable. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1960, 60, 151-174.

CURTIS, J. W. A study of the relationship between hypnotic susceptibility and intelligence. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1943, 33, 337-339.

DARLEY, J. G., & McNAMARA, W. J. Minnesota Personality Scale: Manual of directions. New York: Psychological Corporation, 1941.

DAS, J. P. Hypnosis, verbal satiation, vigilance, and personality factors: A correlational study. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1964, 68, 7278.

DAVIS, L. W., & HUSBAND, R. W. A study of hypnotic suggestibility in relation to personality traits. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1931, 26, 175-182.

DECKERT, G. H., & WEST, L. J. The problem of hypnotizability: A review. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1963, 11, 205-235.

EVANS, F. J. The Maudsley Personality Inventory, suggestibility and hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1963, 11, 187-200.

EVANS, F. J., & THORN, WENDY F. Questionnaire scales correlating with factors of hypnosis: A preliminary report. Psychological Reports, 1964, 14, 67-70.

EYSENCK, H. J. Dimensions of personality. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1947.

EYSENCK, H. J., & FURNEAUX, W. D. Primary and secondary suggestibility: An experimental and statistical study. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1945, 35, 485-503.

FAW, V., & WILCOX, W. W. Personality characteristics of susceptible and unsusceptible hypnotic subjects. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1958, 6, 83-94.

FRIEDLANDER, J. W., & SARBIN, T. R. The depth of hypnosis. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1938, 33, 453-475.

FURNEAUX, W. D. The prediction of susceptibility to hypnosis. Journal of Personality, 1946, 14, 281-294.

FURNEAUX, W. D. Hypnotic susceptibility as a function of waking suggestibility. In L. M. LeCron (Ed.), Experimental hypnosis. New York: Macmillan, 1956. Pp. 115-136.

FURNEAUX, W. D. Neuroticism, extraversion, drive and suggestibility. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1961, 9, 195-214.

FURNEAUX, W. D. The heat-illusion test and the structure of suggestibility. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1964, 12, 169-180.

FURNEAUX, W. D., & GIBSON, H. B. The Maudsley Personality Inventory as a predictor of susceptibility to hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1961, 9, 167-177.

GUILFORD, J. P. Fundamental statistics in psychology and education. (3rd ed.) New York: McGrawHill, 1956.

HATFIELD, ELAINE C. The validity of the LeCron method of evaluating hypnotic depth. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1961, 9, 215-221.

HATHAWAY, S. R., & MCKINLEY, J. C. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory: Manual. New York: Psychological Corporation, 1951.

HILGARD, E. R., & BENTLER, P. M. Predicting hypnotizability from the Maudsley Personality Inventory. British Journal of Psychology, 1963, 54, 6369.

HILGARD, E. R., & LAUER, L. W. Lack of correlation between the California Psychological Inventory and hypnotic susceptibility. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 1962, 26, 331-335.

HILGARD, E. R., WEITZENHOFFER, A. M., & GOUGH, P. Individual differences in susceptibility to hypnosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1958, 44, 1255-1259.

HILGARD, E. R., WEITZENHOFFER, A. M., LANDES, J., & MOORE, ROSEMARIE K. The distribution of susceptibility to hypnosis in a student population: A study using the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale. Psychological Monographs, 1961, 75(8, Whole No. 512).

HULL, C. L. Hypnosis and suggestibility. New York: Appleton-Century, 1933.

ISRAELI, N. Experimental study of hypnotic imagination and dreams of projection in time: I. Outlook upon the remote future -- extending through the quintillionth year. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1953, 1, 49-60.

LANG, P. J., & LAZOVIK, A. D. Personality and hypnotic susceptibility. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 1962, 26, 317-322.

LeCRON, L. M. A method of measuring depth of hypnosis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1953, 1, 4-7.

LEVINE, K. N., GRASSI, J. R., & GERSON, M. J. Hypnotically induced mood changes in the verbal and graphic Rorschach: A case study. Rorschach Research Exchange, 1943, 7, 130-144.

LEVITT, E. E., BRADY, J. P., & LUBIN, B. Correlates of hypnotizability in young women: Anxiety and

94 CORRELATES OF HYPNOTIZABILITY

dependency. Journal of Personality, 1963, 31, 52-57.

LEVITT, E. E., LUBIN, B., & BRADY, J. P. On the use of TAT Card 12M as an indicator of attitude toward hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1962, 10, 145-150.

LEVITT, E. E., LUBIN, B., & ZUCKERMAN, M. Note of the attitude of hypnosis in volunteers and nonvolunteers for an hypnosis experiment. Psychological Reports, 1959, 5, 712.

LONDON, P. Subject characteristics in hypnosis research: Part I. A survey of experience, interest, and opinion. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1961, 9, 151-161.

LONDON, P., COOPER, L. M., & JOHNSON, H. J. Subject characteristics in hypnotic research: II. Attitudes towards hypnosis, volunteer status, and personality measures. III. Some correlates of hypnotic susceptibility. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1962, 10, 13-22.

McBAIN, W. N. Imagery and suggestibility: A test of the Arnold hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1954, 49, 36-44.

MELEI, JANET P., & HILGARD, E. R. Attitudes toward hypnosis, self-predictions, and hypnotic susceptibility. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1964, 12, 99-108.

MESSER, A. L., HINCKLEY, E. D., & MOSIER, C. I. Suggestibility and neurotic symptoms in normal subjects. Journal of General Psychology, 1938, 19, 391-399.

MOORE, ROSEMARIE K. Susceptibility to hypnosis and susceptibility to social influence. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stanford University, 1961.

MURRAY, H. A. Thematic Apperception Test: Manual. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univer. Press, 1943.

ORNE, M. T. The nature of hypnosis: Artifact and essence. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1959, 58, 277-299.

ORNE, M. T. Implications for psychotherapy derived from current research on the nature of hypnosis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 1962, 118, 1097-1103. (a)

ORNE, M. T. On the social psychology of the psychological experiment: With particular reference to demand characteristics and their implications. American Psychologist, 1962, 17, 776-783. (b)

PETRIE, ASENATH. Repression and suggestibility as related to temperament. Journal of Personality, 1948, 16, 446-448.

ROSENTHAN, D. L., & TOMKINS, S. S. On preference for hypnosis and hypnotizability. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1964, 12, 109-114.

ROSENTHAL, R. On the social psychology of the psychological experiment: The experimenter's hypothesis as unintended determinant of experimental results. American Scientist, 1963, 51, 268-283.

ROSENZWEIG, S. The experimental study of repression. In H. A. Murray (Ed.), Explorations in personality. New York: Oxford Univer. Press, 1938. Pp. 472-491.

ROSENZWEIG, S., & SARASON, S. An experimental study of the triadic hypothesis: Reaction to frustration, ego-defense, and hypnotizability: I. Correlational approach. Character and Personality, 1942, 11, 1-19.

SARASON, S., & ROSENZWEIG, S. An experimental study of the triadic hypothesis: Reaction to frustration, ego-defense, and hypnotizability: II. Thematic apperception approach. Character and Personality, 1942, 11, 150-165.

SARBIN, T. R. Rorschach patterns under hypnosis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 1939, 9, 315-318.

SARBIN, T. R. Contributions to role-taking theory: I. Hypnotic behavior. Psychological Review, 1950, 57, 255-270.

SARBIN, T. R., & MADOW, L. W. Predicting the depth of hypnosis by means of the Rorschach test. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 1942, 12, 268-271.

SCHAFER, R. A study of personality characteristics related to hypnotizability. Unpublished master's thesis, University of Kansas, 1947.

SCHNECK, J. Hypnoanalysis, hypnotherapy and Card 12M of the Thematic Apperception Test. Journal of General Psychology, 1951, 44, 293-301.

SCHULMAN, R. E., & LONDON, P. Hypnotic susceptibility and MMPI profiles. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 1963, 27, 157-160.

SCRIPTURE, E. W. Tests on school children. Educational Review, 1893, 5, 52-61.

SECTER, I. I. Personality factors of the MMPI and hypnotizability. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1961, 3, 185-188. (a)

SECTER, I. I. T.A.T. Card 12M as a predictor of hypnotizability. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1961, 3, 179-184. (b)

SHOR, R. E. The frequency of naturally occurring "hypnotic-like" experiences in the normal college population. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1960, 8, 151-163.

SHOR, R. E. Three dimensions of hypnotic depth. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1962, 10, 23-38.

SHOR, R. E., ORNE, M. T., & O'CONNELL, D. N. Validation and cross-validation of a scale of self-reported personal experiences which predicts hypnotizability. Journal of Psychology, 1962, 53, 55-75.

SUTCLIFFE, J. P. Hypnotic behavior: Fantasy or simulation? Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Sydney, 1958.

THORN, WENDY A. F. A study of the correlates of dissociation as measured by hypnotic amnesia. Unpublished bachelor's thesis, University of Sydney, 1960.

VENTUR, P., KRANSDORFF, M., & KLINE, M. V. A differential study of emotional attitudes with Card 12M of the Thematic Apperception Test. British Journal of Medical Hypnotism, 1956, 8, 5-16.

WECHSLER, D. The Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale: Form II, Manual for administration and

95 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

scoring the test. New York: Psychological Corporation, 1946.

WEITZENHOFFER, A. M. Hypnotism: An objective study in suggestibility. New York: Wiley, 1953.

WEITZENHOFFER, A. M., & HILGARD, E. R. Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1959.

WEITZENHOFFER, A. M., & WEITZENHOFFER, GENEVA B. Personality and hypnotic susceptibility. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1958, 1, 79-82.

WHITE, M. M. The physical and mental traits of individuals susceptible to hypnosis. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1930, 25, 293-298.

WHITE, R. W. Prediction of hypnotic susceptibility from a knowledge of subject's attitudes. Journal of Psychology, 1937, 3, 265-277. (a)

WHITE, R. W. Two types of hypnotic trance and their personality correlates. Journal of Psychology, 1937, 3, 279-289. (b)

WHITE, R. W. Analysis of motivation in hypnosis. Journal of General Psychology, 1941, 24, 145-162.

WILCOX, W. W., & FAW, V. Social and environmental perceptions of susceptible and unsusceptible hypnotic subjects. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1959, 7, 151-159.

WILLEY, R. R. An experimental investigation of the attributes of hypnotizability. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago, 1951.

WILLIAMS, G. W. Hypnosis in perspective. In L. M.. LeCron (Ed.), Experimental hypnosis. New York:. Macmillan, 1952. Pp. 4-21.

(Early publication received May 24, 1965)