Shor, R. E., Orne, M. T., & O'Connell, D. N. Validation and cross-validation of a scale of self-reported personal experiences which predicts hypnotizability. Journal of Psychology, 1962, 53, 55-75.

Studies in Hypnosis Project, Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts Mental Health Center 2

RONALD E. SHOR, 3 MARTIN T. ORNE, AND DONALD N. O'CONNELL

A. INTRODUCTION

A number of theoretical formulations on the nature of hypnosis have focused upon the subject's relative lack of concern with external reality and his proneness for experiences where external reality is not the major determinant of subjective reality. Many concepts have been used in reference to this phenomenon; for example, dissociation (Janet, et al., circa 1900), altered state of the person (White, 1941), breakdown and fusions of ego boundaries (Kubie and Margolin, 1944), alterations in ego functioning (Gill and Brenman, 1959).

Recent formulations by Shor (1959; 1962a) attempt to account for this phenomenon under the concept of trance. Trance is defined as the extent to which the usual waking orientation to generalized reality has faded into the more distant background of awareness so that ongoing experiences are relatively isolated from the usual kind of critical self-appraisal. Trance is viewed as one of three major constituents of hypnosis and as a major constituent of many related states.

An important deduction from these formulations is the prediction that most individuals who can readily become profound hypnotic subjects have had many profound "hypnotic-like" experiences which have occurred naturally in the normal course of living. The theory supposes that these individuals have the ability to suspend their usual generalized reality-orientation so that "hypnotic-like" experiences can occur. This hypothesized ability has been

1 This study was supported in part by contract AF49 (638)-728 from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, and a grant from the Human Ecology Fund.

2 We wish to thank our co-workers -- Emily F. Carota, Esther Helfman, Jacqueline Mehler-Amati, and Karl Scheibe -- for their critical comments and editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Much appreciation is also due in this regard to Mrs. Elizabeth Scherer.

3 Postdoctoral Fellow, MF-7860-C3, National Institute of Mental Health, Public Health Service.

55

56 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY

termed tranceability which is a component of, but is distinct from, hypnotizability. In other words, it is hypothesized that at least one permanent attribute of mental functioning lies behind the ability to achieve profound hypnosis. Such an attribute, conceived as a cognitive ability, is viewed as cutting across the currently common classifications of personality traits, such as hysteria or submissiveness. 4

In no sense, however, do the writers believe that this attribute is the only determinant of hypnotizability. Undoubtedly there are other cognitive ability factors as well as non-ability factors which contribute to hypnotizability such as attitudes, motives, situational and interpersonal considerations, and perhaps certain personality characteristics. 5

The present paper is deliberately restricted in scope, however, solely to these hypothesized ability components. A paper-and-pencil self-report questionnaire has been developed to elicit reports on experiences which may be indicative of these underlying abilities. The items of the questionnaire were gathered and refined over a period of several years.

The questionnaire is an attempt to devise a measure independent of hypnotizability of ability factors which are hypothesized as components of hypnotizability. The questionnaire is thus not restricted to items which appear to reflect the ability to suspend the usual generalized reality-orientation (tranceability) but includes also items which seem to pertain to any ability for "hypnotic-like" experiences occurring naturally in the normal course of living, independent of the use of special techniques (such as hypnosis, sensory-deprivation, drugs, etc.). It should thus be clear that these hypothesized abilities are of interest in their own right beyond their relationship to hypnotizability; they may provide an independent linkage to a variety of special states where alterations in consciousness have been descriptively noted. 6

In an earlier publication normative data was presented on a briefer, less heterogeneous version of the present questionnaire (Shor, 1960). It was found that naturally occurring "hypnotic-like" experiences were fairly common in the normal college population and that the relative commonness of these experiences was consistent for two somewhat divergent strata of this population.

5 Research is in progress where these many factors are studied simultaneously.

6 For example: road hypnosis, the break-off phenomenon, trance in other cultures, brain-washing, hallucinogenic drug experiences, sensory-deprivation, intense absorbtion and fascination, "mystic" experiences, peak experiences, and the inspirational phase of creativity.

57 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

Recently a number of other investigators have been studying the relationship between unusual personal experiences and hypnotizability. Aas (1960, 1961), Evans (1960), and London (1960) have been using, at least in part, some of our items with encouraging results.

B. THE PERSONAL EXPERIENCES QUESTIONNAIRE

The Personal Experiences Questionnaire in its original long form, as used in this research, is a paper-and-pencil self-report inventory of 149 items which inquires about a wide variety of naturally occurring "hypnotic-like" experiences. All questionnaire items were phrased positively so that the amount of agreement to each item was expected to correlate positively with criterion measures of hypnotizability.

On the front page of the questionnaire, space was allotted for the commonly requested identifying information such as subject's name, age, sex, and so forth. There followed a brief description of the questionnaire and instructions. This information is reproduced below.

Description and Instructions. In this questionnaire we are interested in a variety of experiences which occur in the natural course of living and which tend frequently to be ignored. The questions are concerned only with experiences which occur naturally, not in dreams nor as the result of drugs nor of special techniques (such as hypnosis or sensory-deprivation).

Normal individuals are able to recall a wide variety of such experiences when asked to do so. Please make an honest effort to remember as accurately as possible.

You are to describe your experiences in two different ways. First in terms of frequency -- that is, how often have you had the experience described. Secondly in terms of intensity -- that is, how vivid and profound the single most intense experience was. Intensity is distinct from frequency. It is possible, for example, to have had a certain experience very frequently, but never to have had it particularly vividly or intensely. It is also possible to have had a certain experience rarely, perhaps only once in a lifetime, and yet with extraordinary vividness and intensity.

You are to give the two kinds of answers in the following way:

(1). Frequency: Under each question there is a scale with seven subdivisions: never, very rarely, rarely, occasionally, often, very often, and always. You are to read through each question and then rate yourself on this seven-point scale by placing a circle around the most appropriate answer.

(2). Intensity: When referring to intensity forget about how frequently you have had the experience. Select only the most intense experience you have had. Then do one of three things:

(a). if the single most intense of these experiences was quite vivid

58 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY

or profound place a single check mark in the right hand margin beside the question.

(b). if the single most intense of these experiences was extremely profound, intense or vivid place two check marks in the right hand margin beside the question.

(c). if the single most intense of these experiences was not profound or vivid put nothing at all in the right hand margin.

Check or double check for intensity as many or as few of the questions as you wish. However, answer all questions as to frequency. If in doubt make your best guess.

Among the topic areas covered in the questionnaire were the following overlapping categories: (a) the activities of sleeping or preparing for sleep; (b) the characteristics of dreams or dreaming; (c) the ability to concentrate and to achieve a quieting of mental activities; (d) the amount of freedom which the individual allows himself in emotional expression; (e) naturally occurring trance experiences; (f) suggestibility in everyday life situations; (g) temporary loss of awareness of generalized reality when mentally absorbed or preoccupied ; (h) the extent of deliberate control of attentional processes ; (i) sensory illusions in waking and hypnogogic states ; (j) amnesias, absentmindedness, or unusual forgetting in everyday life; (k) naturally occurring illusions and hallucinations; (l) the extent to which an imaged or pseudo-reality has ever become temporarily indistinguishable from the actual reality; (m) artistic, mystical, transcendental, and profound religious experiences with altered consciousness; (n) detachment, depersonalization, and estrangement from self or reality.

The following are typical items in the questionnaire: (a) Have you ever had part of your body look strange and not part of your body at all? (b) Have you ever found yourself staring at something and for the moment forgotten where you were? (c) Do you ever get seasick at ocean movies? (d) Have you ever had the experience of walking in your sleep? (e) Have you ever felt drunk while sober? (f) Have you ever become so absorbed in listening to music that you almost forgot where you were? (g) Have you ever felt a oneness with the universe, a melting into the universe, or a sinking into eternity? (h) Have you ever been able to ignore pain? (i) Do you ever get unusually sleepy when reading dull material? (j) Has everything in your line of vision become blurry or strange, as if you were dreaming? (k) Do you find yourself unwittingly adopting the mannerisms of other people? (l) Have you ever had the experience of seeming to watch yourself from a distance as if in a dream?

The Personal Experiences Questionnaire was administered concurrently

59 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

to two independent groups of subjects among batteries of other psychological tests, including measures of hypnotizability. The questionnaire data from one of these samples were analyzed first and without reference to the data from the other sample. The sample analyzed first will be called in this paper the validation sample. The results of analyses upon the validation sample compared against a scale of hypnotic susceptibility were then used as the basis for analyzing the questionnaire data in the remaining sample. This sample, analyzed second, will be called in this paper the cross-validation sample.

C. THE VALIDATION SAMPLE

The section leader of an introductory psychology class of 51 students at Brandeis University administered to the group the Personal Experiences Questionnaire among a number of other paper-and-pencil questionnaires. With variable amounts of urging 29 of these students, or 57 per cent, later agreed to participate in hypnotic testing with the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (Weitzenhoffer and Hilgard, 1959). Nineteen of these students were male, ten were female. 7

D. REDUCTION OF DATA

Item-validity coefficients of correlation were computed for each item of the Personal Experiences Questionnaire using as criterion the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale scores. The main objective of this validating procedure was to select for cross-validation those items which seemed the most promising predictors of hypnotizability. For computational ease the simple phi coefficient (chi-square) was chosen as the correlation index. Statistical significance was determined in terms of the upper tail of the probability distribution. It was decided to select for cross-validation only those items which would yield a degree of positive association statistically significant at or beyond the .05 point; i.e., with a constant N = 29, a phi coefficient of + .31 or above.

These item-validity phi coefficients were computed separately for the frequency and intensity questionnaire measures.

E. FREQUENCY MEASURES

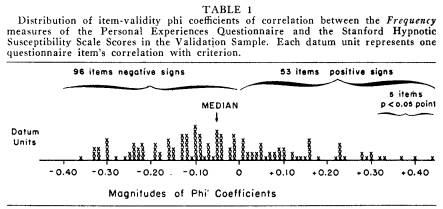

In Table 1 is presented the distribution of the item-validity phi coefficients for each item's frequency measure.

60 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY

1. Findings

Of the 149 items only 53 or 36 per cent yield the expected positive correlations with the criterion measure of hypnotic susceptibility. The median phi coefficient is -.05. The trend in this sample is thus in the direction opposite to prediction. Moreover, on the Null Hypothesis of equal binomial probability of positive and negative signs, chi-square is equal to 11.84 which with one degree of freedom has a corresponding two-tailed probability less than the .001 level which would be considered statistically highly significant had there been no previous prediction of direction. Only five items or 3 1/2 per cent meet or exceed the minimum cut-off standard of phi = +.31, too few to be significant by combined probabilities, and certainly far too weak a demonstration of positive association to be of any practical use as a predictor of hypnotizability. Thus, except for the suspicion of a very slight and unexpected negative relationship, findings with the frequency measure are null.

F. INTENSITY MEASURE

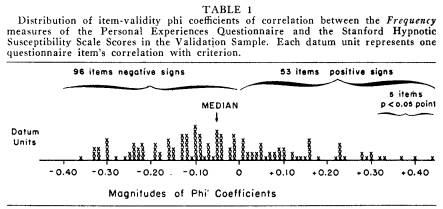

In Table 2 is presented the distribution of the item-validity phi coefficients for each item's intensity measure.

Of the 149 items 141 or 95 per cent yield the expected positive correlations with the criterion measure of hypnotic susceptibility. The median phi coefficient is +.22. Only eight phi coefficients have negative signs and all but one of these is a correlation lower than -.10. On the Null Hypothesis of equal binomial probability of positive and negative signs chi-square is equal to 117.2 with one degree of freedom. The exact probability of this occurrence was computed through the binomial expansion and the odds

61 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

against this difference being a chance event are so astronomically huge (p < 10 to the -33 power) that there can be no reasonable statistical doubt of the existence of a positive association between the intensity measure and the validity criterion of hypnotic susceptibility. Moreover, since the datum units

are themselves correlation coefficients the findings are very convincing statistical testimony to the consistency (reliability) among items. Forty-five items or 30 per cent of the total meet or exceed the minimum cut-off standards of phi = +.31. These statistically most promising 45 items scored for intensity were then selected for cross-validation. 8

G. THE CROSS-VALIDATION SAMPLE

The Personal Experiences Questionnaire was administered among a battery of other psychological tests to a carefully selected group of 25 college students from various universities in the Boston area. All but 6 of those

62 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY

selected were individuals who had had hypnotic training and had participated in hypnotic experimentation with our research project. In many cases their contact with us as hypnotic subjects had extended over a period of a year or longer.

The purpose was to secure a sample consisting mainly of subjects whose level of hypnotic performance was already well-known, who then in repeated hypnotic sessions could be trained to their furthest limits of hypnotizability or at least to the point where it seemed most unlikely that any appreciable improvement would occur. Had a more random sampling procedure been used (as in the Validation Sample) a more normal distribution of hypnotizability undoubtedly would have emerged. Our purpose, however, was not to try to match the shape of the hypnotizability distribution in the college student population but rather to study more fully the two extreme ends of that distribution. The more stratified sampling procedure used resulted in a greater frequency of representation in the theoretically more interesting extremes.

H. ORDER OF PROCEDURES

The order of the experimental procedures reported in this paper utilized with these 25 subjects was as follows: (a) selection of subjects; (b) self-administration of the Personal Experiences Questionnaire; (c) administration of the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale; and (d) diagnosis of maximum achieved depth in hypnotic evaluative sessions.

1. The Personal Experiences Questionnaire

The intensity scores for the 45 Personal Experiences Questionnaire items previously validated were summated into a single intensity measure for each of the 25 subjects. The odd-even reliability coefficient computed for these intensity measures, corrected by the Spearman-Brown formula, is r = +.95. 9

2. Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale

The Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale was administered throughout by one of the writers (D. N. O'C.).

3. Hypnotic Evaluative Sessions

The controversy regarding universal hypnotizability remains unresolved; i.e., whether with unlimited time and ingenuity everyone eventually could be

63 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

profoundly hypnotized. Nevertheless, our recurring experience has been that for most subjects most of the time a plateau in hypnotic performance is soon reached after which no appreciable improvement occurs regardless of the hypnotist, methods used, or amount of further training. It was thus decided for the purposes of this sample to define hypnotizability as the maximum hypnotic depth actually achieved in as many hypnotic training sessions as the experimenter needed in order to feel confident that a stable plateau had been reached.

Thus, regardless of any prior knowledge of a subject's level of hypnotic performance, a minimum of one further session was given. In these sessions the experimenter was allowed freedom to utilize any hypnotic techniques which seemed appropriate and to explore clinically any issues which might then help maximize performance. All hypnotic sessions were administered by one of the writers (M. T. O.). For estimates of inter-judge reliability another of the writers (R. E. S.) observed all of these sessions through a one-way screen with audio arrangements.

Both the experimenter and the observer independently formed ratings of maximal hypnotic depth achieved. These ratings may best be described as clinical diagnoses by experienced hypnotists based upon both objective hypnotic behavior and subjects' report. Four general groupings or categories of depth (hypnotizability) were established: (a) Less Than Light; (b) Light; (c) Medium; and (d) Deep. Plus and minus intermediate ratings were also assigned, but it was decided to ignore these lesser subdivisions for many of the first stages of data analysis. The experimenter's depth ratings were correlated with the observer's depth ratings and found to be just about identical (r = +.96). It thus seemed legitimate to average the two sets of ratings to form a single Over-all Depth Rating. The four major depth categories used are for all practical purposes entirely consistent with the understandings of these terms in common usage and descriptively correspond to the major divisions of the Davis-Husband scale (1931).

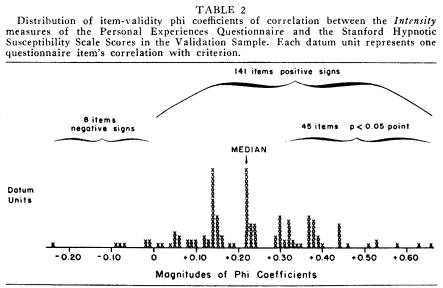

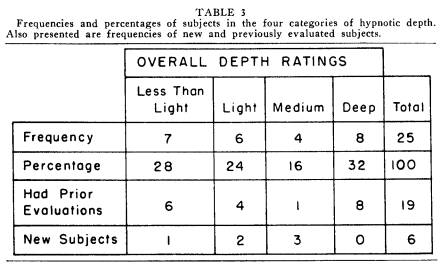

In Table 3 are presented the frequencies and percentages of subjects classified into each of the four major categories of hypnotic depth by the averaged experimenter-observer ratings. Also presented for each category are frequencies of new and previously evaluated subjects.

It may be observed that a roughly equal percentage of subjects were classified into each of the four categories of depth; i.e., the distribution is roughly rectangular. It is also of interest to note that all of the eight Deep Hypnosis subjects were individuals who had had prior evaluations.

64 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY

I. RESULTS

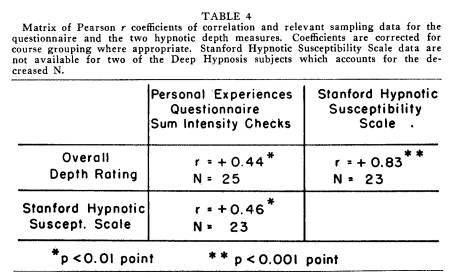

In Table 4 is presented a matrix of Pearson r coefficients of correlation with associated probabilities for the questionnaire and the two hypnotic depth measures. The variable hypnotizability is assumed throughout to have underlying continuity and thus the Pearson r coefficients are corrected for

65 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

course groupings where appropriate as discussed by Guilford (1950; pp. 359-361).10

There is a high correlation between the two hypnosis measures, +.83, which means that about 70 per cent of the variance between these two quite different measures of hypnotic depth is accountable in terms of their measure merits in common.

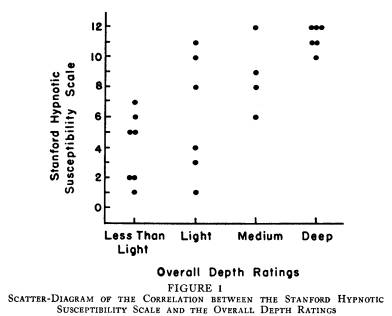

In Figure 1 is presented a scatter-diagram of this correlation. Note that all of the Deep Hypnosis subjects on whom Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale information is available received scores of 10 or more. 11 It is this tighter cluster of scores for the Deep Hypnosis subjects which has considerable influence in yielding a higher coefficient of correlation than might seem indicated by visual inspection of the scatter-diagram.

11 The Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale is scored in terms of certain specific objective behavior. Inquiries with the Deep Hypnosis subjects after testing clarified that all failed items were subjectively successful; as, for example, the individual who objectively does not brush away a bothersome mosquito but who subjectively hallucinates doing so.

66 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY

Observe also that 4 of the 7 subjects classified as Less Than Light in the Over-all Depth Ratings received Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale scores between 5 and 7, which is the middle region of the Stanford Scale's distribution. Notice also the wide distribution of Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale scores for the subjects classified into the Light Hypnosis category.

Both of the hypnosis measures, the Over-all Depth Ratings and the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale, correlate singly with the questionnaire measure about +.45. While these two coefficients indicate only low to moderate correlations they are each statistically significant with an associated probability less than the .01 point.

A multiple correlation between the questionnaire and a combination of the two hypnosis measures is R = .47 which means that there is no appreciable gain in prediction of questionnaire responses by using the two hypnosis measures together as compared with using either one singly.

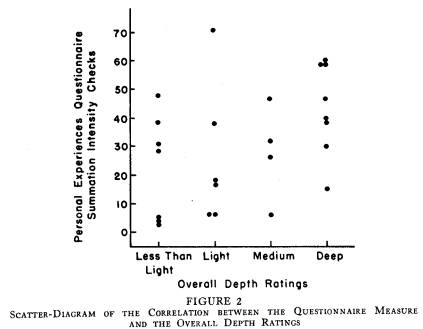

In Figure 2 is presented a scatter-diagram of the relationship between the questionnaire measure and the Over-all Depth Ratings. By visual inspection of the scatter-diagram it is only with some effort that the correlation

67 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

can be seen, and even then the association seems apparent only in the divergence between the Deep Hypnosis ratings and all three of the other ratings combined. The correlation between the questionnaire measure and the Over-all Depth Ratings when the Deep Hypnosis ratings are excluded is r = +.17 ; i.e., the relationship virtually disappears. In other words, the questionnaire measure does not appear appreciably related to this particular measure of hypnotizability from Less Than Light up through Medium Hypnosis.

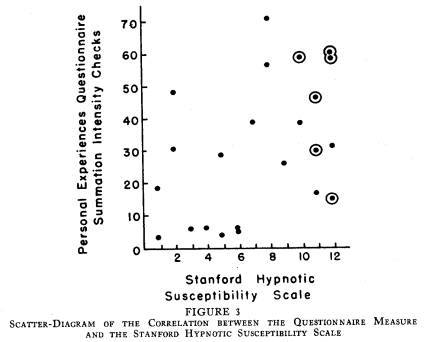

In Figure 3 is presented a scatter-diagram of the relationship between the questionnaire measure and the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale scores.

The correlation, although mathematically no higher than the one just discussed, appears visually to be more apparent over a wider range of the hypnotizability measure. Encircled in the scatter-diagram are the datum units for the subjects classified as Deep in the Over-all Depth Ratings. Re-computing the correlation when excluding these Deep Hypnosis subjects yields a coefficient of r = +.33 which suggests some association but does not quite achieve statistical significance (p > .10 < .20 point).

68 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY

J. DISTINCTIONS WITHIN THE DEEP HYPNOSIS CATEGORY

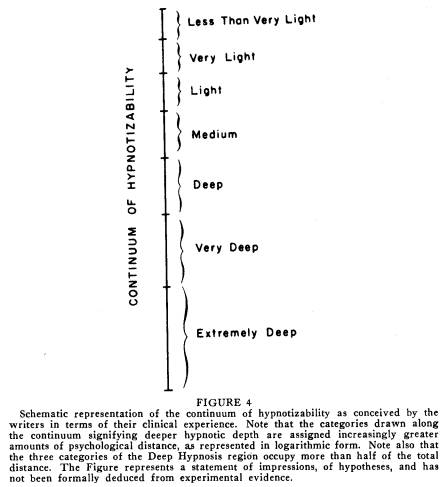

It has long been the clinical impression of the writers that many of the distinctions on the continuum of hypnotizability of the greatest theoretical interest lie within the Deep Hypnosis region. It has also been our view that the psychological distance on the hypnotizability continuum occupied by the Deep Hypnosis region is even greater than the distance occupied by all of the categories of lesser hypnotic depth combined. In other words, we feel that the continuum of hypnotizability might be best depicted schematically in logarithmic form, as in Figure 4. 12

One of the primary guiding objectives behind the design of our research was to explore the relationship between the Personal Experiences Questionnaire and hypnotizability within the Deep Hypnosis region. While only 8 of the 25 subjects were classified in the Over-all Depth Ratings as Deep, exceptional effort was devoted to carefully evaluating the level of hypnotic performance of these 8 subjects in order to sub-classify them into the three categories of Deep Hypnosis cited in Figure 4; (a) Deep, (b) Very Deep; and (c) Extremely Deep.

In order for a subject to have been classified anywhere within the Deep Hypnosis region he had to be able to manifest readily and reliably all of the following criterion phenomena when sampled: (a) suggested blanket amnesia which resists concerted attempts at disruption after awakening; (b) somnambulism and reasonably complex post-hypnotic effects; and (c) hallucinations and interactions with a fantasied environment (for example, age-regression) .

The Deep Hypnosis subjects were then further classified into the three subdivisions of the Deep Hypnosis region in terms of very careful diagnoses of the following:

a. Deep. All of the criterion phenomena readily producible either very well or at least to a moderate extent but subjectively not always fully convincing to the subject himself as he reports afterwards on what it was like at the moment of the experience.

b. Very Deep. All of the criterion phenomena readily producible but occasionally in a less than fully complete form. Mostly subjectively convinc-

69 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

ing to the subject but occasionally with some uncertainty about its utter reality at the moment of the experience.

c. Extremely Deep. All of the criterion phenomena readily producible in their most complete form with the fullest subjective conviction.

K. RESULTS

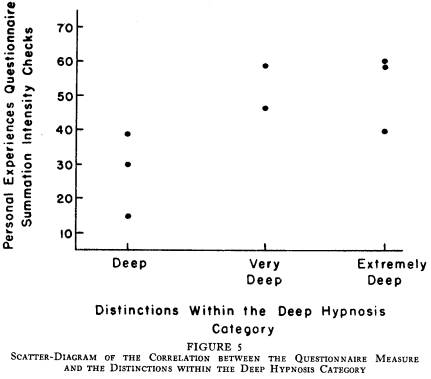

In Figure 5 is presented a scatter-diagram of the correlation between the questionnaire measure and the distinctions within the Deep Hypnosis category.

70 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY

There appears to be a marked relationship with no overlap between the questionnaire scores for Deep as compared with the remaining two subdivisions. The corrected Pearson r for this relationship is +.84 which is of course highly significant statistically (p < .005 point). This finding appears to indicate that the questionnaire measure has high predictive potency in the deeper region of the hypnotizability continuum. Moreover, the correlation is significantly greater statistically than the questionnaire measure's virtually inconsequential predictive potency in the Less Than Light through Medium Hypnosis region cited earlier.

L. RECAPITULATION OF THE EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS AND NON-INDEPENDENCE AS A POSSIBLE SOURCE OF CONFOUNDING

On a random sample of 29 subjects the Personal Experiences Questionnaire was validated as a predictor of hypnotizability as measured by the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale. The frequency measure emerged as

71 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

having no demonstrable practical value. The intensity measure, however, proved both reliable and valid. The 45 statistically most promising items scored for intensity were selected for cross-validation.

A special non-random sample of 25 students whose level of hypnotic performance was generally already well-known was used for cross-validation. It was found that the questionnaire measure was both internally very highly reliable, r = +.95, and correlated significantly with both the Overall Depth Ratings and the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale about r = +.45. It was also found that the questionnaire measure did not appear to be appreciably related to the Over-all Depth Ratings from Less Than Light up through Medium Hypnosis. A similar, but perhaps less severe, decrease in correlation was observed for the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale when the Deep Hypnosis subjects were excluded.

Careful distinctions in hypnotizability had been made among the 8 Deep Hypnosis subjects. A high correlation, r = +.84, was found between the questionnaire measure and these Deep region distinctions.

Scientific caution requires that a possible general source of confounding in the experimental design be kept in mind while interpreting the evidence. In planning the cross-validation sample it was decided deliberately to forego double-blind methodology. For this particular special sample it was not possible to achieve rigorous independence of judgments in regard to the characteristics of subjects already so well-known. It was felt, however, that additional purity at this stage could only have been had at too great a sacrifice in ground covered. It would thus be unwise to interpret our results as not requiring more scrupulous experimental corroboration.

In spite of reservations appropriate to the lack of independence it is warranted to conclude that the results are a modestly convincing demonstration that the questionnaire measure evolved is very highly reliable and is a valid predictor of hypnotizability, and most clearly so in the deeper region of the hypnotizability continuum.

M. DISCUSSION AND THEORETICAL EXTRAPOLATION

The over-all generalization which may be drawn from the study is as follows: there is reasonable evidence that the questionnaire as evolved predicts hypnotizability, especially in the deeper region of the hypnotizability continuum; it is less predictive, if at all, in the lighter region.

This generalization is fully congruent with our initial theoretical formulations provided one additional theoretical assumption be made: that just about everyone in the normal college population (from which all of our

72 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY

samples have been drawn) has sufficient of the hypothesized cognitive ability components to achieve an average amount of hypnotizability (Light to Medium depth) if other conditions are favorable. 13 From this assumption it follows that it is these other conditions (the hypothesized non-ability components, such as attitudes and motives) which are the primary determinants of hypnotizability for college student subjects who classify into the lighter and middle region of the hypnotizability continuum. It is only in the Deep and deepest region of the hypnotizability continuum that the possession of exceptionally, high ability becomes an important determinant. Moreover, it is also in these deeper regions that the non-ability factors should in theory become less predictive since they would almost assuredly have to be no worse than slightly unfavorable or the subject would not have achieved Medium or greater depth in the first place. It thus necessarily follows that: (a) the hypothesized ability components are the primary determinants of hypnotizability in the deeper region of the hypnotizability continuum; and, contrariwise; (b) the hypothesized non-ability components are the primary determinants of hypnotizability in the lighter region of the hypnotizability continuum. It follows further that a multiple correlation composed of both ability and non-ability factors would predict hypnotizability along the entire continuum of hypnotizability.

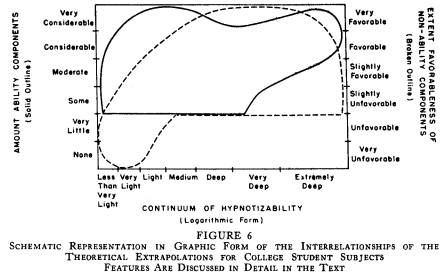

These theoretical deductions, while fully consistent with our findings, are, of course, extrapolations beyond them. As a convenient aid to comprehending the many interrelationships of these theoretical extrapolations, a schematic representation of them is presented in graphic form in Figure 6.

In the Figure are represented the shapes of the theoretically expected correlations for college student subjects between depth on the continuum of hypnotizability and the two hypothesized major component factors. The continuum of hypnotizability, in logarithmic form, is presented along the abscissa. The Figure thus represents the superimposition of two 2-dimensional graphs sharing the common abscissa, and therefore is actually 3-dimensional.

The left hand ordinal scale represents six general qualitative distinctions in amount of ability components; none, very little, some, moderate, considerable, and very considerable. The general shape of this variable's correlation with hypnotizability is represented as the area enclosed by the solid outline on the graph.

73 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

The right hand ordinal scale represents six general qualitative distinctions in extent favorableness of non-ability components; very unfavorable, unfavorable, slightly unfavorable, slightly favorable, favorable, and very favorable. The general shape of this variable's correlation with hypnotizability is represented as the area enclosed by the broken outline (dashes) on the graph.

The area enclosed by the solid outline is depicted as predictive of hypnotizability mostly in the deeper regions; the area enclosed by the broken outline is depicted as predictive of hypnotizability mostly in the lighter regions.

The solid outline is horizontally truncated along the base to represent the assumption that just about everyone in the normal college population has at least a modest amount of the hypothesized ability components. The broken outline also is horizontally truncated along the base from about Medium hypnotizability and deeper. This is to represent the expectation that an individual who achieves Medium or deeper hypnotizability would almost assuredly have no worse than slightly unfavorable non-ability components else he would not have achieved Medium or deeper hypnotizability in the first place.

Observe that the vertically highest portion of the solid outline in the deepest region of hypnotizability is no higher than the vertically highest portion in the Light to Medium region. Note however that there is a dip in between.

74 JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY

This theoretically predicted dip is a logically necessary deduction from the above hypothesis that an individual who achieves Medium or deeper hypnotizability would almost assuredly have no worse than slightly unfavorable non-ability components. It follows that an individual with no worse than slightly unfavorably non-ability components and very considerable ability components would probably achieve hypnotizability in the deepest regions rather than just in the Deep.

Observe that the way the two correlational outlines intercross suggests the likelihood of a fairly high multiple correlation to predict hypnotizability from the two factors. The suggested multiple correlation is hopefully displayed as somewhat approaching R = .80, provided that the non-linearities and lack of homoscedasticity are properly taken into account. 14

The many interrelationships expressed by this schematic diagram may serve as a fairly exact theoretical model upon which to compare future findings. It is hoped that it may prove fruitful as an aid and stimulant to further investigation irrespective of its ultimate accuracy.

N. SUMMARY

A questionnaire was developed in an attempt to devise a measure independent of hypnotizability of cognitive ability factors which were hypothesized as components of hypnotizability. The Personal Experiences Questionnaire was constructed as a paper-and-pencil self-report inventory of 149 items which inquired about a wide variety of naturally occurring "hypnotic-like" experiences. On a random sample of 29 college student subjects the Personal Experiences Questionnaire was validated as a predictor of hypnotizability as measured by the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale. The 45 statistically most promising items were selected for cross-validation. A special non-random sample of 25 college student subjects whose level of hypnotic performance was generally already well-known was used for cross-validation. In addition careful distinctions in hypnotizability were made among the 8 most deeply hypnotizable subjects.

The results were a modestly convincing demonstration that the questionnaire as evolved is a predictor of hypnotizability, and most clearly so in the deepest region of the hypnotizability continuum. The findings are interpreted in terms of theoretical formulations where both ability factors and

75 R. E. SHOR, M. T. ORNE, AND D. N. O'CONNELL

non-ability factors (such as attitudes and motives) are viewed as components of achieved hypnotizability. Ramifications are discussed and theoretical extrapolations from the data are presented as an aid and stimulant to further investigation.

REFERENCES

1. AAS, A. Hypnotizability and non-hypnotic experiences, presented at the California Psychological Association Convention, 1960.

2. _______. Personal Communication, 1961.

3. BARRY, J., JR., MACKINNON, D. W., & MURRAY, H. A., JR. Studies in personality. A. Hypnotizability as a personality trait and its topological relations. Human Biology, 1931, 3, 1-36.

4. DAVIS, L. W., & HUSBAND, R. W. A study of hypnotic susceptibility in relation to personality traits. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol., 1931, 26, 175-182.

5. EVANS, F. J. The prediction of hypnotic phenomena from questionnaire items. Unpublished manuscript, University of Sydney, Australia, 1960.

6. GILL, M. M., & BRENMAN, M. Hypnosis and Related States. New York: International Universities Press, 1959.

7. GUILFORD, J. P. Fundamental Statistics in Psychology and Education, second edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1950.

8. KUBIE, L. S., & MARGOLIN, S. The process of hypnotism and the nature of the hypnotic state. Amer. J. Psychiat., 1944, 100, 611-622.

9. LONDON, P. Personal Communication, 1960.

10. SHOR, R. E. Hypnosis and the concept of the generalized reality-orientation. Amer. J. Psychother., 1959, 13, 582-602.

11. ________ . The frequency of naturally occurring "hypnotic-like" experiences in the normal college population. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hyp., 1960, 8, 151-163.

12. ________ . Three dimensions of hypnotic depth, to be published circa 1962a.

13.________ . A technical handbook for the systematic definition of the construct hypnosis, to be published circa 1962b.

14. SUTCLIFFE, J. P. Hypnotic behavior: fantasy or simulation? Doctoral dissertation, University of Sydney, Australia, 1958.

15. WEITZENHOFFER, A. M., & HILGARD, E. R. Stanford hypnotic susceptibility scale, Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1959.

16. WHITE, R. W. Prediction of hypnotic susceptibility from a knowledge of subjects' attitudes. J. Psychol., 1937, 3, 265-277.

17. _______ . A preface to a theory of hypnotism. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol., 1941, 36, 477-505.

Studies in Hypnosis Project Harvard Medical School 74 Fenwood Road Boston 15,

Massachusetts