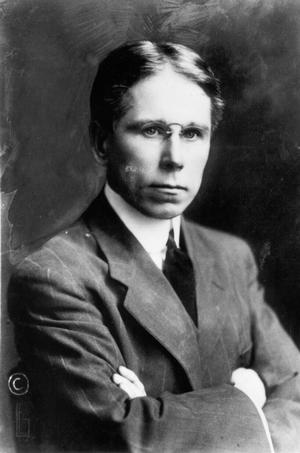

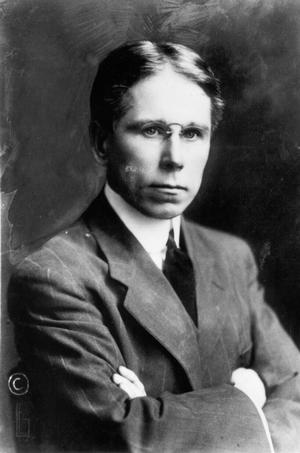

Three members of the Psychological Clinic at the entrance, ca. 1923.

Three members of the Psychological Clinic at the entrance, ca. 1923.

It also illustrated Witmer's clinical method. It was to perform little experiments on his cases (the term he used), in order to understand the nature of their difficulty. As Witmer understood more, he would attempt educational experiments, evaluating their effectiveness over days or weeks. He implicitly assumed that the correct educational approach was to "teach to weakness."

Although his method lent itself best to what we would today call "learning disabilities," articles in The Psychological Clinic attempt to extend the approach to more traditional topic in psychiatry, such as the nature of delusions.

Test materials used in the psychological clinic.

Test materials used in the psychological clinic.

Here is a reproduction of the title page, table of contents, and lead article (the same one as listed above) of Volume 1.

The journal ceased publication in 1935, with a report on the status of clinical psychology in the United States. It reviewed the work of 150 clinics, and it attempted to say something about how psychologists should be educated.

Here is a reproduction of the section of the report about Witmer's clinic at that time.

Witmer as an older man.

Witmer as an older man.

Reflected both in the forumation of goals and the practice of clinical psychology is Witmer's oft-repeated conviction that "there is no valid distinction between a pure science and an applied science. ... What fosters one ... fosters the other." In the final analysis, he added, "The progress of psychology, as of every other science, will be determined by the amount of its contribution to the advancement of the human race."

Students of clinical psychology today, asked to name their intellectual forbears, surely think of Freud before Witmer. The reason for this is perhaps best summarized in an obituary in the American Journal of Psychology (1956, v. 69, pp. 680-682) by Robert I. Watson:

Two significant facets of clinical psychology, as we know it today, were, however, lacking then. The "dynamic approach," to use a convenient shorthand label, was almost completely ignored. He was little influenced by the French psychiatric thought of his day and not at all by Freud. The second missing piece from today's crazy-quilt that is clinical psychology arises from essentially the same omission. This was a lack of clinical collaboration with "analytically oriented" psychiatrists. ... Instead, he turned to men who were primarily neurologists in working out the medical phase of his professional collaboration.

As a result his major influence embodies a paradox. He had less influence upon that body of workers today called clinical psychologists, who in considerable number adopt a dynamic approach and work in psychiatric settings, than upon other psychologists. He was more influential with the workers in those other fields that use the method of clinical psychology but name their areas of endeavor differently. The lineal descendents of Lightner Witmer are found in the far-reaching application of basic clinical psychology to individual problems in education, in vocation and industry, in speech correction, in socio-individual adjustment, a span of interests affecting a wide range of human behavior.

Although Witmer's clinic and Journal are no longer in existence, his conception of clinical psychology forms an important part of the modern department. A clinical program is now an important part of the graduate program. In keeping with the tradition established by Witmer, this program has emphasized the application of the findings of experimental psychology to the study of psychopathology. The program was directed by Julius Wishner from 1957 to 1976, and then by David Williams, Martin Seligman, Robert DeRubeis, and Dianne Chambless.